Zeynep is a Research Fellow working on the Conflict Research Programme. Her research focuses on conflict, economy and gender in Iraq.

The Islamic State’s (ISIS) violence against the Yazidis, a community with historical roots in the Sinjar area of northern Iraq, in the summer of 2014 has received huge international attention. ISIS executed thousands of Yazidis and took large numbers of women and children as hostages. At least 10,000 Yazidis were killed or kidnapped and those that managed to escape the brutal attacks were displaced and are still living today in displacement camps scattered around Iraqi Kurdistan, albeit some moved to Western countries as refugees. Several thousand Yazidis remain unaccounted for. The identification and documentation work, including examining mass graves, is continuing. Due their dwindling numbers and dispersion across Iraq and all around the world, they fear the end of the Yazidi existence as a community in Iraq and find it hard to envision a future for their community there.

There is a push for the treatment of the Yazidi community at the hands of ISIS to be officially recognised as genocide and many experts have defined it as such. Yet so far official international recognition of ISIS’s attacks against the Yazidis as genocide has not come through. However, several international organisations, including the UN Human Rights Office of the High Commission, have defined this premeditated campaign of violence as genocide that involved mass executions, abductions, forced conversions and sexual violence.

The atrocities the Yazidi community faced brought the society, which was already a small population of less than half a million, to the brink of disappearance. This has been compounded by the fact that remaining Yazidis are unable to go back home as their villages and towns have not been rebuilt. There is broken trust and resentment towards their non-Yazidi neighbours back home, either for helping ISIS attack the Yazidis, undertaking similar actions themselves or for not offering protection. There is also ongoing resentment towards government security forces who failed to offer adequate protection. Therefore, the issue of criminal and social justice needs to be carefully addressed for Yazidis to envision a future for themselves in Iraq.

I went to Iraq last summer and talked to members of the Yazidi community, including community leaders, everyday Yazidis and survivors, to understand the impact of the atrocities on their community. Needless to say, these experiences have left lasting scars, trauma and resentment. Yet alongside this, this process has also led to unexpected outcomes.

One of these outcomes is that the Yazidi community’s views towards sexually attacked women and girls has significantly altered to become more accepting. Several female survivors who were held captive by ISIS and exposed to sexual and other forms of violence were hesitant about returning to their families and communities, fearing that they would be rejected or their male family members would kill them.

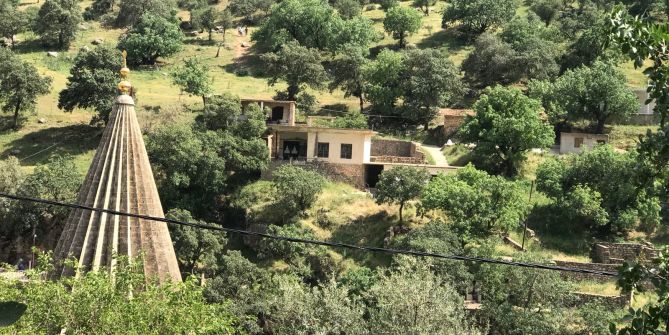

However, the Yazidi religious authority, Baba Sheikh, declared a fatwa (religious decree) welcoming Yazidi women and girls who were in held in ISIS captivity to return to the faith and community free of stigma. They were defined as ‘angels’ and ‘victims’ by the Sheikh and were baptised in Lalish, the Yazidi temple, paving the way for their wider acceptance by the community.

Moreover, despite the taboo around sexual violence and rape in the Yazidi community, several survivors have talked about their experiences. Male community leaders and members, including brothers, fathers and husbands of survivors, have also openly talked about this issue. In fact, with the return of Yazidi survivors, some Yazidi men’s attitudes towards women’s position in general has started to change – for instance, now men feel they should give girls more space and enrol them in education so that they are better able to protect themselves in the future.

However, readjustment and acceptance have not been easy. Survivors and their families are traumatised, and the stigma of being sexually assaulted continues. The issue of children born of war is probably the most difficult issue to resolve for the Yazidi community. If Yazidi women and girls had children by their captives, these children are usually not accepted by the community because, according to the faith, both parents have to be Yazidi for a child to be Yazidi. Several of these children have been sent to orphanages in Erbil and Baghdad and there are efforts to relocate mothers abroad with their children. This response reflects a desire to prioritise community cohesion, even if it comes at the expense of the children and their mothers.

Another impact of the atrocities is the increase in Yazidis’ engagement with international platforms. Activists, both in the region and diaspora, are striving to have ISIS’s atrocities against Yazidis to be defined as genocide, such as the recent Nobel peace prize winner Nadia Murad, a survivor who campaigns for ISIS perpetrators to be held accountable. These activists are making Yazidi voices heard by utilising international legal and policy frameworks on genocide and sexual violence in conflict. Even though such crimes committed during conflicts typically go unprosecuted due to low reporting rates, fear and stigma, the very existence of such legal frameworks facilitated Yazidi activists and their supporters to demand justice and bring these demands to an international agenda.

Other factors also facilitated the increase in Yazidis’ international engagement. ISIS’s high profile on the international agenda increased media attention on the group and its activities, including its attacks on the Yazidis (albeit the media sensation around the concepts of ‘sexual violence’ and ‘slavery’ actually did significant harm to the community and survivors due to insensitive and intrusive methods). Another factor that promoted their international engagement was the long-term presence of international humanitarian and development work in Iraqi Kurdistan.

From the perspective of the Yazidis, they had to change their attitude towards female Yazidi survivors, increase their interactions with the international community and be open about sharing their experiences. Their collective memory of historical trauma and past tragedies played an important role in this reaction. All the Yazidi community members I interviewed defined ISIS’s attacks against their community as the last firman. Firman was a name given to decrees and military campaign orders by the Ottoman sultans, and in the Yazidi vernacular it defines violent attacks and persecutions against their community in the past. The fact that they have experienced yet another attack to their existence, especially in this century, pushed the community to re-position itself within Iraq and internationally. They believe that they came to the verge of destruction as a community in 2014 and they need the whole world to know about this.

Note: The CRP blogs gives the views of the author, not the position of the Conflict Research Programme, the London School of Economics and Political Science, or the UK Government.

1 Comments