Lockdowns were first used in England over 400 years ago. Did the public comply? PhD candidate, Charlie Udale, develops an original approach to measuring the extent to which plague quarantine regulations were followed. By identifying changes in the patterns of burials, he finds strong evidence that the early modern public did indeed follow the rules. That they did is evidence of widespread support for early public health policies.

When lockdowns were imposed by states across the world to reduce the spread of COVID-19 they were met with overwhelming public support and very high rates of compliance. In fact, voluntary social distancing contributed more to the decline in mobility than official policy during in the early phase of the epidemic in advanced economies (IMF, 2020).

Has the public always supported – even pre-empted – heavy state intervention during epidemics or were responses to recent lockdowns a distinctly modern phenomenon? Using new evidence on patterns of infection during plagues in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, I show that Elizabethan lockdowns worked effectively, and suggest this reflected general acceptance of the value of quarantine against epidemics.

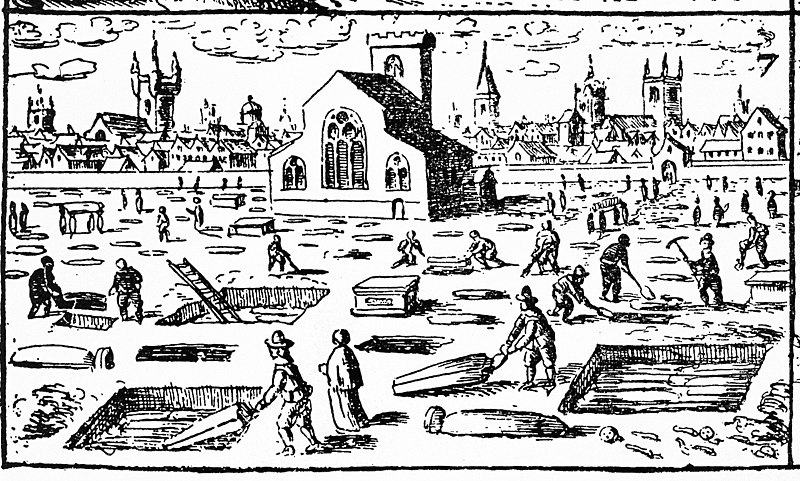

State-enforced quarantines were first developed in response to the recurrent waves of plague which hammered European populations for around 350 years following the initial outbreak in 1347 – the ‘Black Death.’ Quarantine policies were developed by the Italian city states and their trading partners in the Mediterranean. Quarantine was imposed at ports, city gates, districts, and upon households. By the 17th century, much of Western Europe had adopted similar strategies.

Historians have traditionally emphasised public resistance to these measures, especially the ‘shutting up’ of whole households inside their homes once one member was identified as sick. These moments stand out in the historical record, revealing an important part of the contemporary feeling towards novel, highly invasive, and illiberal public health policies.

But are moments of resistance representative or are they just the most visible reactions? Has public opinion really shifted from outrage and resistance to support and compliance during the last four and a half centuries, or was there always a large and generally silent majority who supported these measures, perhaps as an effective way to ensure their own safety?

Measurement is the greatest obstacle to answering this question. Modern governments measure behavioural changes using a range of sources, including traffic and payment flows, surveys, and polls, and, controversially, data taken from GPS and mobile phone applications. Of course, much of this data cannot be recreated in an early modern context.

Historians have relied on written orders, proclamations, or account books generated through the enforcement process. Alternatively, they interrogated contemporary descriptions in correspondences to understand the extent to which quarantine rules were enforced and complied with. These approaches have revealed much about public health responses to plague epidemics and the negative reactions they provoked. Yet none are suitable for measuring population behaviour like modern states.

I use changes in patterns of mortality to measure compliance with early modern quarantine policies in a new and more direct way. Prior to the creation of a rigorous quarantine policy in England, healthy people living alongside the sick could still interact with the wider community. The Plague Orders of 1578 changed this. They required the whole household to stay indoors once one person became sick and, like today’s furlough system, facilitated this through the state provision of food and necessities where needed. For those who tried to leave, the state empowered watchmen to use violence to repel them.

My approach relies on one key assumption: locking up the healthy alongside the infected increased the chance of plague spreading within the household. I use this effect of household quarantine – an increase in the clustering of burials within affected households – to investigate the extent of enforcement and compliance with household quarantine policy.

I compare the level of mortality within affected households in three plague epidemics that occurred in Bristol between 1565 and 1604. The epidemics of 1565 and 1575 came before household quarantine was adopted as a national policy response to plague in 1578. The third epidemic happened after the adoption of household quarantine, in 1603-4.

Figure 1 presents data for the 9 (of 18) Bristol parishes for which data survives for all three epidemics (representing more than half of the population). The vertical axis represents the proportion of all burials that were registered during an epidemic that could be linked, using surnames, into groups of three or more.

The consequences of household quarantine are stark. Before the adoption of a household quarantine policy, around a quarter of burials could be attributed to households where at least two other people had died. In the first plague to strike Bristol after the adoption of quarantine policies, 45% of burials could be attributed to households where at least two others had died – an increase of 80%. Burials were more tightly clustered into household groups because the new household quarantine rules were enforced and complied with.

By understanding changes in mortality within affected households, historians can measure behavioural changes in a similar way to modern states. Applying this approach to a case study of early modern Bristol has revealed just how extensive behavioural change could be, even in epidemics that occurred 400 years ago.

Whilst the early modern state was open about its willingness to use violence to ensure compliance, the system could never have functioned, just as today, without widespread cooperation from the public. When we look at which areas showed the highest rates of compliance, it was wealthier parishes – and often better off households. Whilst there have always been some people willing to stand up against state backed lockdowns, the majority have kept their head down, complied, and hoped to escape with their lives.

References

Caselli, F., Grigoli, F., Lian, W. & Sandri, D. Protecting Lives and Livelihoods with Early and Tight Lockdowns. [Washington, DC]: International Monetary Fund (2020).