Third year LSE undergraduate Hiro Shu uses a demographic analysis of Hong Kong to reveal its demographic and economic vitality after the Joint Declaration in 1984 which transferred sovereignty to China after 150 years of British colonial rule. In the process he draws important parallels to modern tensions between China and Hong Kong and reveals the implications of this for Taiwan.

By undermining the principal of ‘one country, two systems’, the introduction of the National Security Law (2020) led to the highest rate of emigration in Hong Kong’s history. This has severely impacted Hong Kong’s economy with Singapore overtaking Hong Kong as the world’s third-largest international financial centre in 2022.

The ‘two systems’ principle was originally developed as the basis for a political relationship between China and Taiwan. It was introduced in Hong Kong with the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984. By revealing the demographic vitality of Hong Kong in the decade following the Joint Declaration, my research suggests the introduction of the National Security Law has undermined what could have been a successful blueprint for future relations between China and Taiwan.

The Joint Declaration of 1984 validated the transfer of sovereignty of Hong Kong back to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on 1 July 1997, after over 150 years of British colonial rule.

Using population censuses from the years 1986, 1991 and 1996, I find that the proportion of the local population increased in line with the general population in Hong Kong and the city became more cosmopolitan in the decade following the Joint Declaration. Furthermore, I find that immigration outpaced emigration in the lead-up to the 1997 handover. Hong Kong thrived in the ‘two systems’ period.

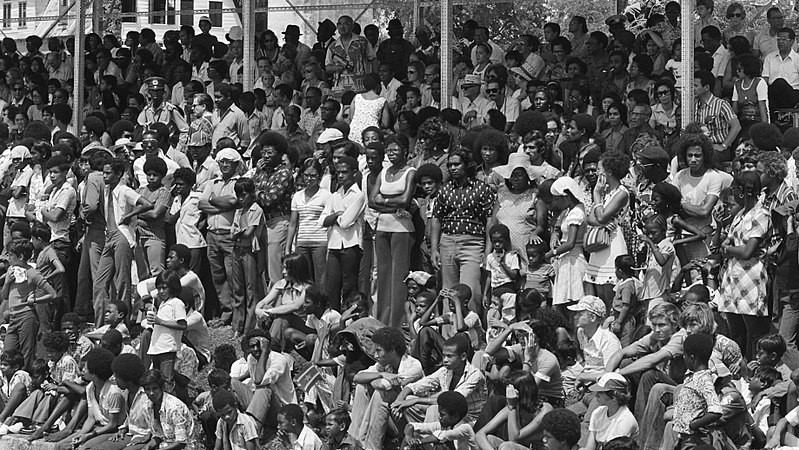

The decade preceding the Joint Declaration was characterised by economic expansion, welfare extension, and the emergence of a new middle class with a distinct Hong Kong identity. By the 1970s, the children of the refugee migrants of the 1950s were coming to maturity, and unlike their parents, had no substantial connection to the mainland. When the Joint Declaration was signed, these Hong Kong ‘belongers’ were left with two options: political participation or emigration.

The population of Hong Kong grew substantially following the Joint Declaration, with above trend growth among those born outside of Hong Kong or China (figure 1). Hong Kong’s total population increased by 2.34% from 1986 to 1991 and 12.59% from 1991 to 1996. Growth over the same periods was far less strong for those born in China (-4.87% and 6.54%). Whereas the share of the Hong Kong population born elsewhere in the world experienced very rapid increases (65.65% and 37.80%) – far above the average.

Analysing these changes by nationality, instead of place of birth, shows that the share of the population who were British citizens with a right of abode outside of Hong Kong increased by 156.04% between 1991 and 1996, a more than twelve-fold increase compared to the general population growth trend. Chinese citizens increased by 3.05%, while the percentage increase in citizens of other nationalities was 65.25%.

Consistent with this above trend increase in the share of foreign nationals, the share of the Hong Kong population who spoke English as their usual language/dialect also grew well above trend, increasing by 61.55%. Putonghua (Mandarin) speakers, the official language of the PRC, grew in line with the population at 14.44%, while the share who spoke other Chinese dialects decreased by 6.71%. The share of the population who spoke other languages also increased well above trend at 50.06%.

Whether we look at birthplace, nationality or language/dialect, the evidence is clear: Hong Kong became considerably more cosmopolitan following the signing of the Joint Declaration in 1986.

Comparing my data on immigration between 1986 and 1994 with Skeldon’s data on emigration provides a more nuanced description of population flows in Hong Kong.1 While the Joint Declaration increased emigration in the subsequent decade, this was more than offset by immigration in the lead-up to the 1997 handover (figure 2). The growth rate for emigration is 2.26% across the whole period whilst the growth rate for immigration is 3.83%. Except for 1989, Hong Kong experienced very little net migration between 1986 to 1991. The trends diverge thereafter, with immigration increasing significantly.

The explanation for the trend in emigration is complex and cannot be attributed to any single factor. The growing anxiety amongst the Hong Kong population certainly played its part. The Tiananmen Square incident of 1989 likely exacerbated the situation. This is supported by the emigration estimates – from 1990 to 1994, the number of emigrants only dipped below 60,000 once. Many of the emigrated Hong Kong population returned after securing the right of residence in their destination countries. Another significant factor that contributed to the steady growth in emigration is the increase in overall immigration intake in the principal destination countries for the Hong Kong population, namely, Canada, Australia, and the United States.

The acceleration of immigration into Hong Kong in the 1990s reflects skilled foreign personnel looking to take advantage of the high-salary, low-tax environment in its booming economy. The influx of skilled human capital contributed to the city’s economic prosperity, with per annum growth rates averaging roughly 5.5% in the early 1990s. As a result, Hong Kong strengthened its position as a global financial centre as the value of commercial and financial services soared.

The population response to the Joint Declaration contrasts sharply with those following the implementation of the National Security Law in 2020 where China essentially reneged on the ‘one country, two systems’ principle established by the Joint Declaration. Since then, Hong Kong has experienced a continuous net outflow of citizens with no signs of a slowdown in the trend. In 2021, Hong Kong’s population decline was the largest in the city’s recorded history.

Unlike those who left in the early 1990s, it is unlikely this new wave of emigrants will return to Hong Kong. The outflow of human capital has already permeated through to the economy with Singapore overtaking Hong Kong as the world’s third-largest international financial centre. The implementation of the National Security Law has therefore made peaceful reunification between China and Taiwan more challenging. The Joint Declaration was originally devised with Taiwan in mind. The demographic and economic vitality that followed offered proof of its potential. The undermining of this model has now shattered a compelling argument for ‘one country, two systems’ in the context of Taiwan as well.

References:

[1] Ronald Skeldon, “Hong Kong Communities Overseas,” in Hong Kong’s Transitions, 1842-1997, ed. Judith M. Brown and Rosemary Foot (Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1997), pp. 121-148, 134.