Employers often think they’re communicating well, but they use ‘neurotypical’ standards of interacting, writes Brett Heasman

Autism is a lifelong developmental disability that affects how people connect and relate to others and also how they experience the world around them.

Most non-autistic people are not aware of the complex ways in which autistic people* experience the world and are not adequately prepared for interacting or working with autistic people. Autism is a ‘hidden’ disability, with no external physical signs, and it encompasses a huge range of people, behaviours, abilities and challenges which, for many non-autistic people, takes time to appreciate and understand.

The gap in public understanding of autism has very real consequences for employment prospects. Only 16 per cent of autistic adults are in full-time work despite 77 per cent of those unemployed wanting to work. This employment figure has not changed since 2007 and remains significantly lower than the average employment figures for people belonging to other disability categories (47%.) In short, something is going seriously wrong in the workplace for autistic people to be so disproportionally unemployed.

Social world and impression management challenges

That autistic people are disadvantaged is not surprising, given how we have built a world heavily dependent on tight social coordination with others. Access to any employment opportunity requires candidates to navigate the social encounter of the interview, while even getting to the stage of an interview in the first place requires the ability to build social capital and network with others. For people who have life-long difficulties in social interaction, the social process of finding employment remains a considerable obstacle. A lack of eye contact, or a silence that lasts too long can have very negative consequences for rapport. Yet autistic people may give off these signals unintentionally, which is why employers need to look past small-scale social cues to take a broader perspective on what is meaningful interaction.

Relationship challenges and the ‘double empathy problem’

Building professional relationships is another critical issue. I have worked throughout my doctorate with a charity that supports young autistic adults, and have seen how quickly professional and personal relationships can break down.

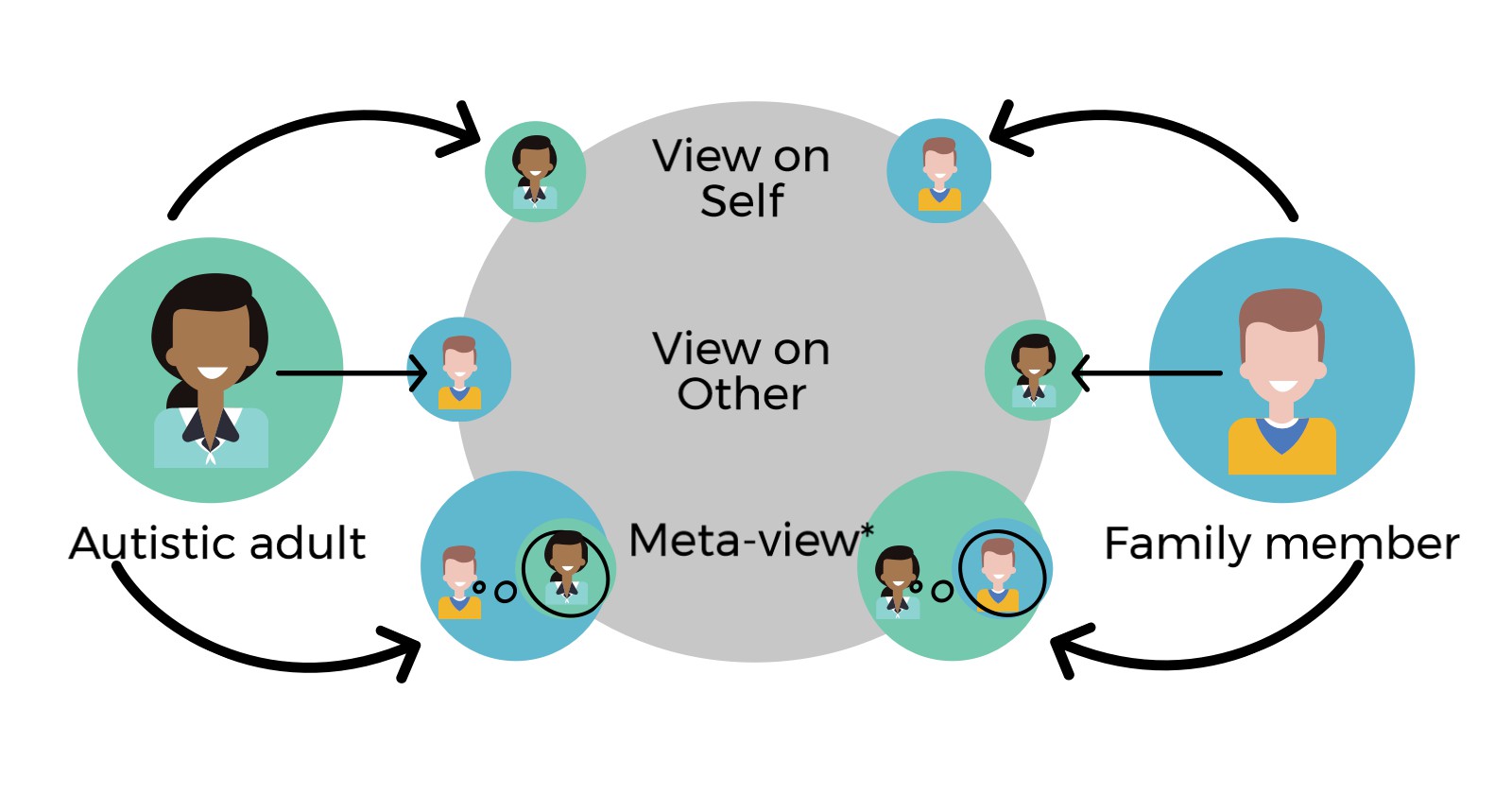

A recent study conducted by myself and Dr Alex Gillespie, LSE, has shed new light on why this may be the case. We examined family relationships between autistic adults and their family members and found that many misunderstandings did not always originate from the autistic adult. Family members were often incorrectly taking the perspective of autistic relations, seeing them as more ‘egocentrically anchored’ in their own perspective than they actually were. This misunderstanding raises an important question regarding the assumptions used by non-autistic people to evaluate autistic people. It is evidence of the ‘double empathy problem’, a persisting gap in mutual understanding because both sides of a given autistic/non-autistic relationship have different normative expectations and assumptions about what the ‘other’ thinks.

Case study of a professional autistic relationship

I recently visited a workplace where a trainee had been diagnosed with autism and was finding that his relationship with his employers was very difficult to manage. In particular, he had very low self-esteem, was uncomfortable with the constant change to his schedule, and did not like having to attend meetings particularly because it left him feeling criticised which would inevitably affect his other activities for the day.

From the employer’s perspective, they were very keen to show that they had been adapting to his particular way of working within what they perceived to be reasonable adjustments. However, there were still some points that I had to clarify to the employers which highlight the ‘double empathy problem’ in action.

For example, it emerged that in meetings, the autistic employee would often misunderstand what had been said. In response, the employer stressed that they had no problem with the meeting being stopped if the autistic employee wanted to ask a question or clarify a point of discussion. Yet this is a problematic assumption, because the autistic employee may not realise a misunderstanding has taken place until much later, when it had manifested into a problem, and even if he did recognise in the moment that there was a misunderstanding, it should not be assumed that he would be able to “speak up” instantly.

Speaking up is a very difficult social skill, where one must assess the dialogue, look for moments of verbal interjection, and give a non-verbal signal to ‘take control of the floor’ just prior to speaking. It requires an acute reading of the social situation, and no small amount of confidence to perform.

Another challenge was the employer was very focussed on developing strategies for the employee to embrace and work with ‘constructive criticism’ in order to improve the way in which the team worked as a whole. I suggested that it might also be a good idea to run over the positive things which the autistic employee had done. From the employer’s perspective, this had not seemed particularly necessary because many of the positive aspects were deemed obvious. However, when I spoke to the autistic employee it was very clear that he had no idea what it was that he did well, and because of his low self-esteem, would often downplay compliments.

This highlights another disjuncture in the relationship that needed to be addressed. The employer needed to give much more positive feedback, even on tasks that seemed obvious and inconsequential, because it could not be assumed that the autistic employee shared the same level of certainty about what was good or bad practice.

These two examples show how the employer believed good communication was already in place, when in fact their model of communication was framed around ‘neurotypical’ standards of interacting. Undoubtedly the employer was keen to do the best for managing the professional relationship and had already made many adjustments, but these examples show how deep-rooted our social reading of others is ingrained, and how much opportunity remains to improve public and employer understanding of autism through listening to what autistic people have to say.

Figure 1. Psychological structure of relationships (Heasman and Gillespie, 2017)

Notes: * Meta-view = how one person thinks they are seen by the other person. Misunderstandings can easily persist if one’s meta-view aligns closely with one’s view on the other. Source: Heasman and Gillespie, 2017.

* The author has chosen to use the term ‘autistic people’ given the majority preference of participants he has worked with and feedback from national surveys

In the video below, Brett Heasman discusses his recently published paper Perspective-taking is two-sided: Misunderstandings between people with Asperger’s syndrome and their family members, co-authored with Alex Gillespie, Autism Journal, July 2017.

In the video below, Brett Heasman discusses his recently published paper Perspective-taking is two-sided: Misunderstandings between people with Asperger’s syndrome and their family members, co-authored with Alex Gillespie, Autism Journal, July 2017.

♣♣♣

Note(s)

- This article was first published in LSE Business Review blog on 31 July 2017 and is being republished with relevant permissions.

- About the author: Brett Heasman is a PhD student in the Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science at the London School of Economics (LSE), specialising in public understanding of autism. His research is published in journals including Autism and Current Opinions in Critical Care. He has worked for several years as both a carer and researcher with autistic people, and has won grant awards for collaboration and impact from the ESRC and LSE respectively. In 2017 he created the ‘Open Minds’ exhibition to promote autistic voices and improve public understanding of autism, which has been featured in an article by The Lancet Neurology, the world’s leading neurological journal. Twitter: @Brett_Heasman Autism is the topic of the author’s ongoing research for his PhD dissertation with LSE’s Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science.

- Featured image credit: Eyes, by Dboybaker, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

Thank you for this article. I have ASD. I do exceptional work in my field but experience similar workplace issues over and over, finding a need to keep changing jobs. I very much like the phrase you used “tight social coordination with others” as this is an excellent way to help explain.

An entirely relevant article related to the economic wellbeing of the UK economy and those who experience Autism every day.

There remains a chasm of understanding between the neurotypical and the autistic on a fundamental level of facial or other body language. Such misunderstandings are a two-way street, but when fellow employees express the feeling that ‘I just don’t like him/her’ (i.e. the autistic employee) this can lead to discrimination in reporting and appraising and the assessment of ability to work in a team environment. Inevitably the autistic person comes off worst in these often silent expressions of dislike and ‘campaigns of spite ‘ often emerge from the apparent indifference to ostensibly friendly overtures from one side to the other which can then turn nasty. The employer may act to stabilise their business by siding with the ‘normal’ cohort against the inevitably individual autism ‘sufferer’…

What needs to be understood:

Autistic people often see work as just that: they can work as a team member but don’ need to drink in the pub to cement the association.

Misunderstandings in face and body language work both ways: ‘normal’ people mis-read autistic faces and poses as much as the other way round

Autistic workers often appear too conscientious and dedicated to their tasks and this breeds resentment in others whose aim is ‘presenteeism’ as opposed to productivity

The key to management of teams which include autistic workers can be as simple as respecting that those people are there to work: give them time to become comfortable in their environment and a degree of social interaction will develop…

As a high-functioning autistic man in the workplace, I second just about everything that was said . . . and I would like to add a few points.

Bullying is a big problem, and autistic people are natural targets. This is especially relevant at work, as many jobs are competitive when it comes to advancement and (in some jobs) sales.

This means that there is a financial incentive to sabotage an autistic person’s work. This–quite naturally–leads to conflict, and the autistic person is usually the one that gets fired.

I often find myself at a disadvantage when trying to resolve conflicts at work because I have problems with eye contact and body language, and lack of eye contact is often interpreted as dishonesty.

This is similar to the challenges that I encounter in job interviews.

We are, for example, told that a firm, businesslike handshake is important in a job interview . . . but if I’m interviewing an older person who has hands twisted with arthritis, I would not use any pressure at all when shaking this person’s hand. I would like to believe that I wouldn’t hold arthritis against someone in a job interview.

Likewise, eye contact is uncomfortable to me . . . so I’ve been passed over for jobs because this issue is interpreted as dishonesty and/or a lack of sincerity.

So, I become an easy target for bullying, as co-workers are not above exploiting my autistic vulnerabilities to position themselves for advancement and promotion.

Another problem is following rules.

I’ve actually been fired for following company procedures and rules.

As an example, I worked as a security guard in a library. Part of my job was to evict patrons who were sleeping.

I see a guy sleeping, and I go to evict him . . . and he shows me his medical alert bracelet that says he has narcolepsy, so I let him stay.

I then get suspended, because there are no exceptions.

I then end up getting fired, because I evict mothers who come in with baby prams because the baby is sleeping, and there’s no sleeping un the library.

No one can understand that–for purposes of sleeping in the library–that I don’t see a difference between a baby in a baby carriage and a narcoleptic.

I don’t want to be told that I don’t have common sense, because if common sense doesn’t work with the narcoleptic, then why should I expect it to work with a sleeping baby in a pram?

Conflicts like these are what sinks me at work.

In the case of “speaking up” the consequences of getting the timing wrong are that it will be interpreted as “interrupting” or “butting in”.

To autistic people NT non-verbal signals are akin to a foreign language. Even with training they may be unable to “assess the dialogue, look for moments of verbal interjection” or unable to do this and follow what is being said. It The non-verbal signal required to ‘take control of the floor’ may be ignored if it’s it’s not done in exactly the right way and/or right time.