The European Court of Human Rights generally takes five years to decide a case, and the enforcement of its judgements is often dubious and ineffective. Nevertheless, the Court has a role to play in the transformation of human rights culture in the EU and their neighbours, says Başak Çalı, as Turkey’s case proves. The Court’s judgements can help to foster domestic and international debates about the value of human rights.

It now takes an average of five years for the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) to deliver judgements. Yet in the case of Turkey, the spread and the importance of the Turkish case-law lends strong support to the argument that human rights courts have an important function in countries where human rights protections are not entrenched and where the number of rights violations are high.

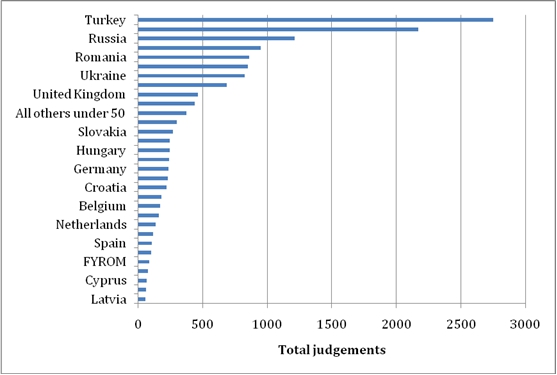

First, the Strasbourg court operates as a ‘barometer’ which can help to identify emerging and continuous problems in law, policies and practices through repeated cases. As Figure 1, below illustrates, Turkey is top of the list of countries with ECHR judgements relating to it.

Figure 1: Total ECHR judgements by country 1959-2011

Source: ECHR

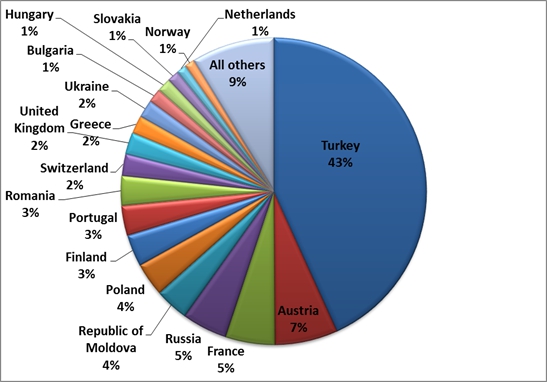

Indeed, between 1959 and 2011 over forty per cent of cases touching on freedom of expression came from Turkey, as illustrated by Figure 2 below. There are similar warning signs for repeated cases regarding the length of detention and respect for fair trial guarantees.

Figure 2: ECHR cases by country on Freedom of Expression 1959-2011

Source: ECHR

Second, the Court of Human Rights has a ‘transformative’ function. By creating a distance from the emotional and political debates that happen in domestic contexts, ECHR is able to offer a reasoned and authoritative statement about the boundaries between rights and the space for politics. This provides leverage and resources for those fighting for the entrenchment of a human rights culture in the domestic legal and political discourse of their countries. The authority of the Strasbourg court comes from the fact that it speaks for a community of states and sets out common standards that should apply to all the other 47 Council of Europe member states. It is this common standard that enables the Court to rise above political and legal disagreements, and that distinguishes the Court’s view from any other.

In the past two years, the legitimacy of the ECHR has been debated hotly in the UK. A central premise of the British objections to the ECHR is that the Strasbourg Court is too interventionist in its dealings with reasonably well functioning domestic institutions. Therefore, the argument goes, standards that apply to the likes of Turkey may not necessarily apply to the United Kingdom. Looking at the Strasbourg Court from Turkey, however, it is precisely the authority of common standards delivered by an all-encompassing and authoritative Court that provide the best justification for improving human rights in the light of ECHR’s judgments.

The relationship between Turkey and the ECHR illustrates why we need human rights courts operating over and above states. Turkey has been no stranger to Strasbourg since first accepting the right to individual petition in 1987. Between 1987 and 2001, the ECHR decided against Turkey in over 2,400 cases, finding at least one violation in 87 percent of these cases. The database of the Committee of Ministers, the inter-governmental watchdog for the implementation of judgments, shows that over 1,700 of these 2,400 cases are yet to be fully implemented. Ten percent of the Court’s much criticized current case-load – over 16,000 cases – consists of Turkish issues.

Turkey is by no means alone in producing daunting Strasbourgeois statistics. Italy has a violation record that matches Turkey’s. Pending cases from Russia have also surpassed Turkey. The UK has cases that have taken longer than those in Turkey to implement judgements. What is significant about Turkey’s relationship with the ECHR is that in the past twenty-five years the judgments of the ECHR have touched virtually all areas of the country’s public policy. This ranges from actions by security forces against the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) to domestic violence; from wearing headscarves at universities to conscientious objection; and from the question of Cyprus to the banning of political parties. The judgments of the ECHR have thus become an intrinsic part of the political and legal discourse on the reach of international human rights in the domestic sphere– a sphere where discourses competing with human rights law (namely variants of nationalism, majoritarianism, and Islamism) have much prevalence.

Has the ECHR succeeded in changing things in Turkey?

Turkey’s relationship with the ECHR also shows that the ability of human rights courts to affect change on the ground is conditional on the domestic institutional culture and the Court’s perceived international authority. Despite the authoritative nature of the judgments of the ECHR, the Court is a distant actor in the implementation of its judgments and in ensuring that future decision-making occurs in accordance with them. This is because domestic institutions, be they national parliaments, the executive or the judiciary, have a primary role of ensuring respect for Strasbourg judgments. Either domestic institutions need to respond to judgments on their own, or they need to be responsive to pressures from domestic civil societies and the international community.

My in depth analysis of cases against the actions of the Turkish security forces between 1996 and 2006 shows that there are significant discursive obstacles to the implementation of human rights judgments in Turkey. That is, domestic institutions in Turkey do not lack any capacity to respond to judgments, but they are primarily hampered by alternative discourses prevalent in the policy areas that human rights judgments address. For example, this is clearly demonstrated in the failure to systematically prosecute members of the security forces and police who have engaged in torture or killings. It is also evident in the refusal of Parliament to address conscientious objection or the case of the name rights for women post-marriage.

My extensive fieldwork in both Turkey and Strasbourg also shows that the avenues for challenging the resistance to human rights judgments are also few and far between. Turkish civil society is itself divided on the issues that human rights judgments address and so does not act as a united bloc for the rule of law. Even in instances where one finds organised civil society playing a supportive role, for example, in countering the discrimination against Alevis in the national curriculum, these organisations are not organised as compliance constituents. The pressure that Turkey faces from Strasbourg often comes too little and too late and is not a viable engine for change in the face of over 1,700 cases.

Despite these weaknesses, the transformation towards a human rights culture cannot but be a long term and on-going struggle. As one human rights lawyer has put it: ‘The good thing about human rights judgments is that they do not disappear. They are always there for activists to fight for.’

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

___________________________________

About the author

Başak Çali – University College London (UCL)

Başak Çali – University College London (UCL)

Dr. Başak Çalı is Senior Lecturer in Human Rights at UCL’s Department of Political Science. Her research focuses on normative and sociological approaches to international law and institutions. Çalı has worked with governmental and non-governmental organisations, including the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the OSCE, NATO, Interights, the Aire-Centre and ESCR-Net.

1 Comments