Many commentators have praised France’s new president François Hollande for appointing half of his cabinet and government’s posts to women. However, Rainbow Murray argues that these appointments are actually less favourable to women than the first Sarkozy government in 2007; most of the key ministerial posts have been given to men.

Many commentators have praised France’s new president François Hollande for appointing half of his cabinet and government’s posts to women. However, Rainbow Murray argues that these appointments are actually less favourable to women than the first Sarkozy government in 2007; most of the key ministerial posts have been given to men.

Last week, the newly elected French president François Hollande unveiled France’s first parity government. Women now hold nine out of eighteen cabinet posts (excluding the (male) prime minister), and 17 out of a total of 34 government posts. This landmark moment comes in the wake of several unfulfilled promises of political parity in France. However, while there is much to be welcomed, the portfolios allocated to women demonstrate that French women still do not enjoy political equality with men.

France first passed a parity law in 2000, requiring all French parties to field equal numbers of men and women to most elections. The law has led to significant improvements in women’s representation in local politics, but has been thwarted repeatedly at the national level, with parties placing women in unwinnable seats and, in some cases, sacrificing millions of euros in state subsidies rather than selecting more women candidates. As a result, the French National Assembly still only has 18.5% women MPs, although this is likely to rise sharply in June’s parliamentary elections.

Meanwhile, the French government has been an anomaly, in that it has frequently contained a higher proportion of women than the National Assembly. This is because the president can appoint women ministers from outside parliament. Although these nominations may appear progressive, many of these women do not have strong power bases of their own, and are therefore dependent on the “fait du prince”, or presidential patronage, which can be used to ensure their loyalty and submission. An early example came in 1995, following the election of President Jacques Chirac. Chirac’s prime minister, Alain Juppé, appointed twelve women to the government. These women were nicknamed “Juppettes” – a patronising play on Juppé’s name that means “short skirts”. Within six months, eight of these women had been sacked.

More recently, Nicolas Sarkozy – who ran against a woman candidate (Ségolène Royal) in 2007 – promised to appoint a parity government if elected. His first cabinet of 15 ministers included seven women, although the wider government was only one-third female. Ministers included a few political heavyweights such as Michèle Alliot-Marie (Defence) and Roselyne Bachelot-Narquin (Health), but also some relative newcomes such as Rachida Dati (Justice) and Christine Lagarde (Finance). As Sarkozy’s presidency progressed, the number of women in government steadily dwindled, especially in the more prominent positions.

It is therefore understandable that Hollande’s promise of a parity government was met with some cynicism, especially after he admitted during the campaign that women might not “have the same responsibilities”. He was true to his word in every sense – women got half the jobs, but a much smaller fraction of the power. He nominated a loyal man, Jean-Marc Ayrault, to be prime minister rather than the more senior, prominent and popular choice, Martine Aubry. Aubry is the party leader and was Hollande’s closest rival for the presidential primary after the fall of Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Aubry’s loyal support to Hollande’s campaign went unrewarded, and her refusal to play second fiddle to Ayrault resulted in her omission from the government altogether. Nor did the other most senior woman, Ségolène Royal, get a ministerial post. Instead, the position of Justice Minister went to Christiane Taubira, a relative outsider and a candidate in the 2002 presidential election for the Radical Left Party.

All other key ministerial posts, including Foreign Affairs, Finance, Interior, Defence, Work and Employment, Education, and Industry, went to men. Women found themselves in the less prestigious, powerful and more stereotypically “feminine” posts such as Social Affairs and Health, Culture and Communication, Senior Citizens, Families, and Disabled People. In this respect, the first Hollande government is actually less favourable for women than the first Sarkozy government in 2007. One consolation was the revival of a fully-fledged Women’s Ministry for the first time since 1986, with its minister, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, sitting in cabinet. Recent research by Conor Little indicates that the posts given to Socialist women were, on average, half as powerful as those going to Socialist men.

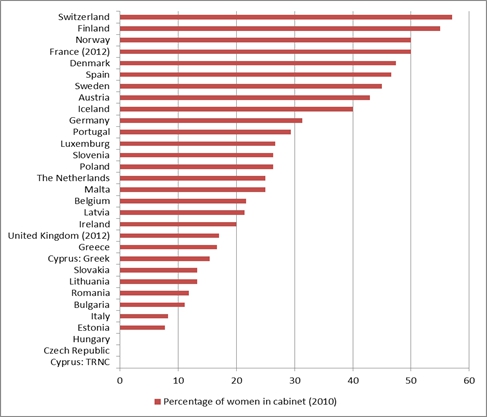

How does France compare to her neighbours? France is not the first country to have a parity government; Zapatero introduced parity governments in Spain, including several women in senior posts, while Nordic countries have long had high levels of women in government. As the figure below shows, in 2010, the percentage of women in governments was 57% (Switzerland), 55% (Finland), 50% (Norway), 47% (Denmark, Spain), and 46% (Sweden). In contrast, the UK is a poor performer. Only 17% of its cabinet is female, with five women and 24 men. Only one woman, Theresa May (Home Secretary), holds a senior position, while Baroness Warsi has no ministerial portfolio. A similar gendered pattern is present in Germany, even though the Chancellor, Angela Merkel, is a woman, as is the Justice Minister, Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger. Yet most senior ministers are men, with women holding the stereotypical posts of Family Affairs, Education, and Social Affairs. France is symptomatic of a wider problem faced by women at the executive level.

Figure1 – Percentage of women in European cabinets

Source: Caramani et al 2011

Overall, France is getting ever closer to its promise of political parity. Unfortunately for women, however, political equality is somewhat further out of reach, with gender stereotypes still rife and the balance of power tipped firmly in favour of men.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/JalShk

_______________________________________

Rainbow Murray – Queen Mary, University of London

Rainbow Murray – Queen Mary, University of London

Rainbow Murray is a Reader in Politics at Queen Mary, University of London, and a visiting research fellow at CEVIPOF (Sciences Po, Paris). Her research interests lie in political representation, gender and politics, candidate selection, French and comparative politics, political parties and elections. She is the author of Parties, Gender Quotas and Candidate Selection in France (Palgrave, 2010) and the editor of Cracking the Highest Glass Ceiling: A Global Comparison of Women’s Campaigns for Executive Office (Praeger, 2010).

So… people who get political appointments on the basis of qualifications other than their appeal to the electorate… don’t have any real power because… they have no policital base of support.

And you’re surprised by this?

Really?

What interests me is why parity in this context can be seen as something positive and non-sexist. surely we should have the right people in the right positions rather than deciding members of governnent cabinets based on genitalia. I find it outrageous and if we truly think that parity is. important the shouldn’t we fight this for other under represented groups? disabled people ? Different ethnic groups ? Different sexual orientations? No. too complicated. but the feminists shout loudest so lets accommodate them. Dangerous no?

I guess this is one of those arguments where from the “original position” (i.e. if we went back to the very start of history and started to discuss how things should work) gender quotas don’t make a lot of sense logically. It makes more sense if we consider that women were excluded from politics for the bulk of our history and that we’re still not entirely free from that.

I’m not sure if I agree with gender quotas indefinitely – if we did manage to eliminate discrimination then you’d still expect it to be lopsided one way or another (it would be a bit of a random coincidence if it was always a 50-50 gender split). Maybe short term there is more justification.