Last week’s elections in the Netherlands saw the mainstream parties of the centre make significant gains over the far-right PVV, led by Geert Wilders. André Krouwel argues that despite the success of the mainstream parties, there is little evidence that the result signifies a return to political stability for the country. The party system is becoming increasingly polarised and the volatile nature of the Dutch electorate ensures that the governing coalition will need to maintain its appeal to voters on the far-left and on the far-right of the political spectrum.

Last week’s elections in the Netherlands saw the mainstream parties of the centre make significant gains over the far-right PVV, led by Geert Wilders. André Krouwel argues that despite the success of the mainstream parties, there is little evidence that the result signifies a return to political stability for the country. The party system is becoming increasingly polarised and the volatile nature of the Dutch electorate ensures that the governing coalition will need to maintain its appeal to voters on the far-left and on the far-right of the political spectrum.

The most surprising outcome of last Wednesday’s Dutch parliamentary elections was neither the victory of the liberals (VVD) nor the good showing of the social democrats (PvdA), but the enormous loss of the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA). In 2010 the CDA had seen its vote share decline from 26.5 per cent to 13.7 per cent, and now they slumped further only achieving 8.5 per cent of the vote, making the CDA only the 5th party in size. Both the anti-immigrant party of Geert Wilders (PVV) and the Socialist Party achieved higher vote shares. Right-wing voters are abandoning Christian democracy en masse, moving towards the liberal VVD of Prime Minister Mark Rutte.

In the immediate post-war period, the Christian democrats (then consisting of three separate parties) accumulated more than 50 per cent of votes and parliamentary seats. As a result, governments in the Netherlands were formed around the centrist Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), coalescing with either the left or right. The pivotal centrist position in the Dutch political landscape allowed the Christian democrats to govern 58 out of the 66 post-war years. For decades the appeal of Christian democracy was that they kept their distance to both the liberals and social democrats by arguing that not the market or the state should be the dominant agent of economics and society, but families, employer organisations, unions and other civil society organisations. Confessional parties favoured consensus democracy in which social partners themselves find solutions for economic problems that government then implements, the now famous ‘Polder-model’.

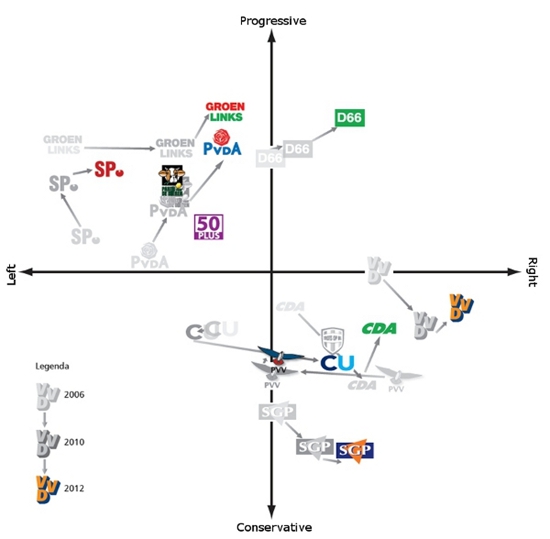

Many voters perceived the last government – the first minority coalition in post-war Netherlands of CDA and VVD with tacit support of the PVV – as a failed political experiment. Internally, the CDA was deeply divided over government formation with Wilders, who fiercely campaigns against the ‘Islamisation’ of Dutch society. Many Christian voters are uneasy with the religious intolerance in that message, while others feel that the CDA moved too far to the right on socio-economic issues. An analysis of the party platforms from 2006, 2010 and 2012, as shown in Figure 1 below, indeed shows that the Christian democrats now adopt a right of centre position on the socio-economic cleavage. The CDA can now be found where roughly the VVD positioned itself in 2006.

Figure 1: Party positions in the Netherlands 2006-2010 based on party platforms

Key to parties (click logo for Wikipedia page)

Centrist politics has all but disappeared from Dutch politics as parties have polarised on the moral-cultural dimension that was politicized by Pim Fortuyn and now by Geert Wilders. Over the last decade, Dutch society became deeply divided over cultural issues, particularly with regard to immigration, integration of (Muslim) minorities and the European Union. The 2005 referendum on the Constitutional Treaty deepened and hardened Euroscepticism, with Geert Wilders now even campaigning for a unilateral Dutch exit from both the Euro and the European Union. In this election, the combined vote share for Euro-critical parties (the PVV, the Socialist Party and the fundamentalist confessional Christian Union and State Reformed Party) amounts to no less than 2.3 million voters – a quarter of the Dutch electorate. The idea that this election is some sort of ‘normalisation’ or return to political stability seems unfounded.

The Dutch constitute one of the most volatile electorates in Western Europe, with large numbers of them deciding very late in the campaign which party they are going to vote for. Ipsos Synovate panel data show that more than 40 per cent of voters were undecided five days before Election Day, while an estimated 15-20 per cent decided on the last day. Most Dutch voters have a high vote propensity for two or even three parties, and can easily switch their allegiance from election to election. Voters are not adrift or ‘floating’ as some may have it, but strategic considerations of coalition potential and the quality of the candidates do enter the equation when deciding whom to vote for.

This might explain why the two best campaigners – Mark Rutte (VVD) and Diederik Samsom (PvdA) – did well. Voters gave Rutte’s VVD its largest vote share ever, rewarding the party’s substantial movement to the right over the last years, visible in the emphasis on fiscal austerity and welfare state cuts by the liberals. Voters on the left favoured the moderate social democrats of Samsom over the more radical Socialist Party. This was not necessarily because left-wing voters did not like the policy stances of the SP, but mainly because they did not regard SP-leader Roemer as a credible alternative Prime Minister that could replace Mark Rutte. The enormous rise in the polls of the PvdA – at a pace of almost one seat a day from late August – was heavily driven by the appeal of its new leader Diederik Samsom. His moderate message of ‘pain now, gain later’ combined fiscal austerity measures with compensations for lower income groups and public investment to boost economic growth. This centripetal tendency of the PvdA is hampered by the fierce electoral competition from the SP, which forces the social democrats to maintain a left-wing profile.

Interestingly, the outcome of the election practically condemns the VVD and PvdA to form a Lib-Lab coalition. This coalition will span the political centre, but not fill it. Its two constituent members need to maintain their appeal to voters that proved very willing to support the more radical options of Wilders’ PVV and Roemer’s SP. Both the electoral gains of PvdA and VVD are fragile and conditional. These centrifugal forces will undoubtedly impact the next government’s attitude towards the EU and the euro-crisis, in particular with regard to financial support for weaker euro-countries. Wilders will continue to accuse Prime Minister Rutte of having ‘the backbone of a mussel’ and ‘handing over our national purse to Brussels’, while the SP will accuse Samsom of breaking down the welfare state and allowing the EU’s open market polices to supress wages. It is far from certain that a ‘Purple’ government of VVD and PvdA will hold under such tremendous pressures. Both will probably explore how to broaden their coalition, but taking on board mathematically unnecessary partners complicates decision-making and potentially threatens the structural reforms of the labour and housing market that are needed to make this government successful.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/OAGvG3

_________________________________________

André Krouwel – Free University in Amsterdam

André Krouwel – Free University in Amsterdam

André Krouwel is an as associate professor at the Department of Political Science of the Free University in Amsterdam. He also leads the Centre for Applied Political Science that he founded, with the aim from the (political) science socially relevant applications. His research focuses on the changing role of political parties in European democracies and the rise (and fall) of new political parties and political ‘entrepreneurs’, from both political and sociological neo-institutional perspective. His most recent book is Party Transformations in European democracies. (SUNY Press, 2012).

3 Comments