The EU’s budgetary framework works in seven year cycles with negotiations now on-going for the upcoming 2014-2020 spending programme. Ahead of a special summit on the EU’s budget next month, Giacomo Benedetto and Simona Milio write that while the budget is relatively small compared to the EU’s gross national income, expected cuts mean that investment programmes which can make a difference in light of the eurozone crisis may be under threat.

The EU’s budgetary framework works in seven year cycles with negotiations now on-going for the upcoming 2014-2020 spending programme. Ahead of a special summit on the EU’s budget next month, Giacomo Benedetto and Simona Milio write that while the budget is relatively small compared to the EU’s gross national income, expected cuts mean that investment programmes which can make a difference in light of the eurozone crisis may be under threat.

The European Parliament and the 27 national governments of the European Union have until next year to approve a new multiannual spending programme for the years 2014 to 2020. Three outcomes are possible: reform, continuity or deadlock. Expenditure from the EU budget is limited to just 1 per cent of the collective gross national income of the EU, equivalent to just 2 per cent of total public spending. In percentage terms, this appears to be rather little, but could total €972 billion for the seven year cycle of 2014-2020, a real terms freeze compared to the previous budgetary period of 2007-2013. Although the budget is small in global terms, it matters because it is what saves the EU from being a mere free trade area, which is precisely what makes it controversial. Within that 1 per cent of gross national income, there are also large subsidies for agriculture and for economically deprived regions, which have real significance.

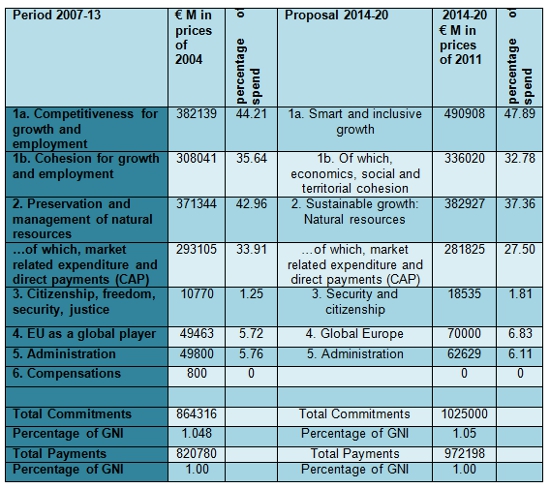

The approval of a new spending programme for 2014-2020, shown in the Table below, faces a number of challenges. Firstly, the rule changes brought in by the Treaty of Lisbon, which do not make decisions easier to reach and which reinforce continuity; second, the effect of enlargement of the EU since 2004 which means that a larger number of players are now found around the table at the negotiations, each with demands for spending and each with the power of veto; and finally, (and most significantly), the effect of the global economic and eurozone crises. These crises have led to three contradictory impulses: for national austerity currently being experienced nationally to be implemented at EU level; the desire to provide public goods, such as investment in innovation and technology to combat the economic crisis; and the drive to protect existing expenditure for traditional EU redistribution in agriculture and regional cohesion in the face of demands for austerity.

Table – EU spending, 2007-13 and Commission proposals for 2014-2020

This month we have published an edited volume on reform of the European Union budget, which brings together contributions that assess the political and institutional processes of budget change, before looking at their possible effects on areas of spending. We include chapters on innovation, public goods, agriculture, cohesion and foreign policy. The book assesses how reform might happen, reviews the theory on budget change in the EU and analyses the impact of the budget rule changes of the Lisbon Treaty. Sara Hagemann’s contribution goes beyond the rules to profile the prospect of negotiating in a different way to achieve a different outcome in keeping with the needs to incentivize economic innovation. As Robert Kaiser and Heiko Prange-Gstoehl reveal, the chance of a new shift in favour of innovation under the area of competitiveness for growth and employment (budget heading 1a, above) is slim given the incentives both to reduce the budget and protect traditional redistribution via agriculture and cohesion. Charles Blankart and Gerrit Koester provide a solution for financing public goods and economic innovation by creating a parallel budget through enhanced cooperation. This means that a sub-group of at least nine member states could produce an additional budget to which only the participating states would contribute and gain benefit. Unlike the agriculture budget, a parallel public goods budget would be reversible since its set-up rules would require unanimous re-approval every few years. We hope that this idea will gain traction given the recent pressure for the eurozone countries to develop a fiscal and budgetary identity separate from that of the EU as a whole.

The chapters on agriculture by Alan Greer and cohesion policy by Simona Milio predict that these policies will remain largely stable, will be oriented further towards the new member states and will be dressed more in the language of public goods, for example by associating agriculture with the environment. In the case of cohesion policy, an orientation away from economic and towards social objectives – for example in employment – could provide greater value through improving the capacity for economic resilience. Budget heading 4 (Global Europe) is predicted to see an increase from 5.7 to 6.8 per cent of the budget. While much of the EU’s external policy is financed and managed by member states, extra resources will be required by the European External Action Service established by the Lisbon Treaty.

The Cypriot presidency has indicated a hope to conclude an agreement by November 2012 in which cuts would apply to all headings. A familiar division is taking place between net contributors and recipients in which public goods appear likely to face a squeeze. The book’s conclusion analyses the outcomes of the two most recent agreements on EU spending in 1999 and 2006 and predicts that continuity will be the result of the agreement of 2013. A deal which includes a small cut but which manages to protect agriculture, cohesion, rebates for the UK and other net contributors, and payments for the poorest member states will be an agreement of the lowest common denominator. An overall cut that protects traditional redistribution in the EU can only be financed by reducing expenditure on public goods that would otherwise have helped to re-invigorate the European economy.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/T8KxXd

_________________________________

Giacomo Benedetto – Royal Holloway, University of London

Giacomo Benedetto – Royal Holloway, University of London

Dr Giacomo Benedetto is a Lecturer in EU and Comparative European Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London. He has published research on the European Parliament, the British House of Commons, the Constitutional and Budgetary politics of the EU and on Euroscepticism. He is currently conducting research on institutional continuity in the European Parliament following the 2004-7 Enlargements of the EU and on the reform of the EU budget.

Simona Milio – LSE Social and Cohesion Policy Unit

Simona Milio – LSE Social and Cohesion Policy Unit

Dr Simona Milio is Associate Director of the Social and Cohesion Policy Unit at LSE where she conducts research on Cohesion Policy for both the European Commission, National and regional governments. She has successfully published on this topic in highly regarded journals such as Regional Studies and West European Politics. Her recent monograph (From policy to implementation in the European Union: the challenge of Multilevel Governance system, September 2010 by I.B.Tauris), explores potential reasons for deficiencies in policy implementation across the EU, using a wide range of Member State case studies.