How can the European Union encourage trade with its immediate neighbours? Peter Havlik explores the EU’s relationship with the ‘European Rim’, an area with a population nearly as great as that of the EU. He writes that in order to increase growth by taking advantage of EU markets, Europe’s neighbours must expand their export capacities and increase their competitiveness. The EU must, in turn, adapt the current approach to its periphery by promoting intra-regional cooperation and reducing regional barriers to trade and cooperation.

How can the European Union encourage trade with its immediate neighbours? Peter Havlik explores the EU’s relationship with the ‘European Rim’, an area with a population nearly as great as that of the EU. He writes that in order to increase growth by taking advantage of EU markets, Europe’s neighbours must expand their export capacities and increase their competitiveness. The EU must, in turn, adapt the current approach to its periphery by promoting intra-regional cooperation and reducing regional barriers to trade and cooperation.

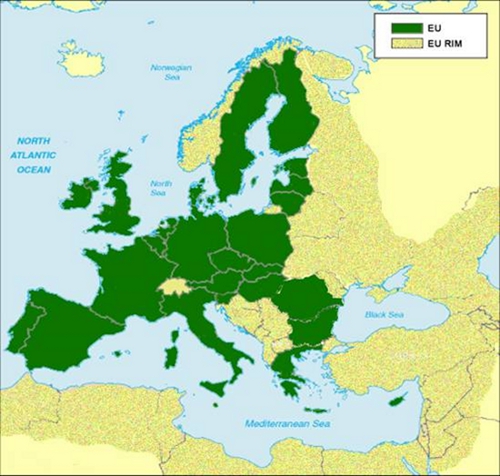

The countries that belong to the ‘European Rim’ (shown in Figure 1, below) are extremely diverse. In economic terms, most of them are small (except Egypt, Russia and Ukraine) and have less-developed, economies (the exceptions being members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) or the European Economic Area (EEA) – Norway, Switzerland and Liechtenstein, which are among the most affluent countries in the world – and Israel, whose GDP per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) is close to the EU average). On the other hand, a number of Eastern Rim countries (e.g. Armenia, Georgia, Moldova), as well as several Middle East and North African (MENA) countries (e.g. Morocco, Jordan and Syria), are fairly poor, with estimated GDP per capita at PPP amounting to less than 20 per cent of the EU average.

Figure 1 – The European Rim

Source: European Rim Policy and Investment Council

However, in terms of population, the total of the Rim countries is close to that of the EU (87 per cent of the EU: 435 million and 501 million inhabitants, respectively), while in terms of total GDP at exchange rates, the overall Rim economy is rather small (23 per cent of the EU: EUR 2,790 billion and 12,260 billion, respectively). Even at PPPs, the estimated aggregate GDP of the Rim countries represents just about a third of the EU’s – still a huge market, especially when its considerable growth potential is taken into account. The individual dimensions of the European Rim all have important implications for EU policies towards the region(s), for EU institutional relations with individual Rim countries and for Rim countries themselves – including their competitiveness.

The EU’s institutional relations towards the Rim are now aimed essentially at the conclusion of bilateral Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTAs) and mobility partnerships with all the countries that are able and willing. The key question now, is whether this approach is adequate (or even appropriate) for such a diverse group of countries and societies. Most of the reviewed literature suggests that it is not. Apart from policies aimed at bilateral trade liberalisation and measures to support the investment climate in the countries concerned, the EU should also promote regional integration and intra-regional cooperation. These initiatives would be helpful especially in the Eastern and Southern parts of the Rim, where regional fragmentation is particularly detrimental.

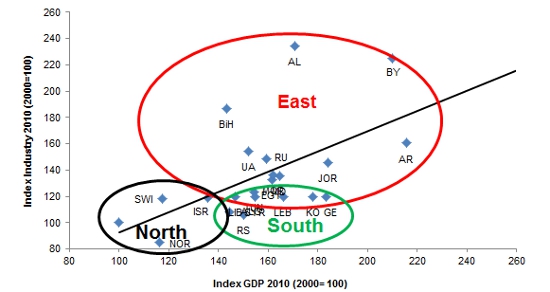

The economic growth of most Rim countries and their progress in catching up (if any) have been the result not of increased exports, but in most cases (apart from energy exporters and tourist destinations) have originated with the expansion of domestic demand; and this has frequently been financed from transfers (aid and remittances to resource-poor countries). The growth of industry in the majority of Rim countries, in particular in the Southern cluster, is lagging behind the growth of GDP, as illustrated in Figure 2. The recent experience of Southeast Europe shows that the pre-crisis neglect in building up a viable trade sector and sufficiently competitive export capacities has aggravated the crisis. Policies leading to expansion of the export sector will have to take priority, and the use of different policy instruments (labour market, investment promotion and institutional development) will have to be strengthened.

Figure 2 Competitiveness of the Rim: growth of industry and GDP, 2000–10

Country key

Source: wiiw.

Source: wiiw.

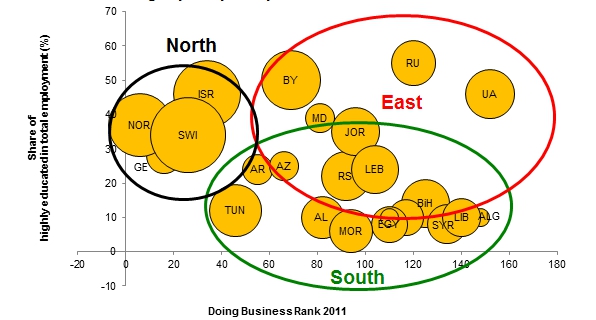

The Rim’s competitiveness is generally low (except for the above-mentioned exceptions in the advanced North), and this is reflected among other things, in the low intensity of manufacturing exports and low foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows. The many reasons for this situation are related to economic backwardness in general, low employment skills and also the poor business climate that particularly affects small and medium enterprises. As Figure 3 shows, the Eastern part of the Rim has been doing somewhat better in this respect than both the Western Balkans and the MENA region in a number of business-relevant areas (such as access to finance, the use of foreign technology, labour market regulations and workers’ skills).

Figure 3 – Competitiveness of the Rim: ease of doing business, employment skills and manufacturing exports per capita

Note: exports per capita in logarithms; proportional to bubbles

Source: wiiw.

The Rim countries are relatively minor trading partners for the EU and do not pose any serious challenge to EU competitiveness. However, the trade asymmetry – the EU being usually the main trading partner of the Rim countries – is challenging, not least for the formulation of EU policies, since any bilateral deal has much greater consequences for the Rim than for the EU. Trade asymmetry and the underutilisation of the trade potential provided by the geographical proximity of the Rim should be overcome. In particular, the proximity of the huge EU market can be regarded as the Rim’s locational competitive advantage – thus far largely unexploited. Each of the sub-regions within the European Rim is a focus area in terms of trade flows for at least one sub-region of the EU. The varying regional specialisation (and interests) of individual EU countries represents another challenge for the formulation of uniform and effective EU policies towards the Rim.

Limited diversification of the Rim’s exports (except for in the advanced North) is one of the greatest stumbling-blocks to the region’s competitiveness. Attempts to improve the international competitiveness of the Rim countries – such as product and labour market reforms, but also liberalisation efforts and improvements in the business climate in general – may not have the desired positive effects. This is because these economies still generally lack both the industrial capacity and the necessary structural flexibility to respond successfully to external competitive pressures. These drawbacks result in high adjustment costs and low gains from liberalisation in terms of an increased emergence of new firms and new export products. This interpretation of the competitive situation of the majority of the European Rim countries (again except for the North) corresponds to the results from an earlier trade simulation exercise, which predicts significant short-term output losses in the European Rim countries in the bilateral liberalisation scenario.

A major impediment to the Rim’s competitiveness is its regional fragmentation. Even within the three sub-regions there are many barriers to trade and business in general (the persisting frozen or open conflicts are obviously not helpful either). Numerous trade barriers exist in both the Eastern and Southern parts of the Rim. In the Southern part of the Rim, the limited intra-regional integration is viewed as the key obstacle to FDI, trade diversification and growth. In the Eastern part of the Rim, attempts at a revival of Russian-led regional integration (the Russia–Belarus–Kazakhstan customs union) have not been encouraged by the EU.

The continuing bilateral ‘hub-and-spoke trade arrangements’ between the EU and the Rim resemble the pre-accession arrangements which the EU concluded with accession countries from Central and Eastern Europe during the 1990s. However, without the proper ‘membership anchor’, such arrangements are probably not sufficient to foster reforms, regional integration and a sustainable development on the Rim. Therefore, the EU needs a more ambitious design for its trade agreements with neighbourhood countries.

Vasily Astrov, Mario Holzner, Gábor Hunya, Isilda Mara, Sándor Richter, Roman Stöllinger and Hermine Vidovic of the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) also contributed to this article.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/WtghrU

_________________________________

About the author

Peter Havlik – The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies

Peter Havlik – The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies

Peter Havlik is the senior researcher and Deputy Director of the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), focusing on issues related to European integration, transition economies, Russia and the former Soviet Union. He has also worked as a consultant to OECD, The World Bank, the European Commission, the Czech and Slovak governments and a number of private companies. He was visiting professor at the Hitotsubashi University Tokyo and the chief economist at the Russian-European Center for Economic Policy in Moscow.