Recent military actions in North Africa and the Middle-East suggest that Europe is heading towards a more active role in defence policy. However the EU’s member states, facing rising costs and reduced spending on defence due to the eurocrisis, are increasingly turning to foreign defence investment to take pressure off national budgets. Daniel Fiott warns that unchecked foreign investment in Europe’s defence industries may entail risks, such as the transfer of technology and classified information. He argues that the EU should supervise this investment to safeguard Europe’s growing defence industry.

Recent military actions in North Africa and the Middle-East suggest that Europe is heading towards a more active role in defence policy. However the EU’s member states, facing rising costs and reduced spending on defence due to the eurocrisis, are increasingly turning to foreign defence investment to take pressure off national budgets. Daniel Fiott warns that unchecked foreign investment in Europe’s defence industries may entail risks, such as the transfer of technology and classified information. He argues that the EU should supervise this investment to safeguard Europe’s growing defence industry.

Recent military actions in Libya, Syria, and now in Mali have reinforced the need for an independent, cost-effective military capability in Europe, especially now that American assistance can no longer be guaranteed. However European states are now finding it increasingly difficult to maintain purely national defence-industrial bases. The demand generated by the European Union’s (EU) Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) for cost effective military capabilities, and the problems posed by the Eurozone crisis, have reduced defence spending in Europe, and the high and rising costs of military equipment and productive duplication (of missiles, tanks, warships) across the EU are all contributing factors.

A country or region’s defence industrial base embodies the productive and policy steering processes that make the development of industrial and technological capabilities, and indeed national defence, possible. Without the industrial and technological means to develop and produce military capabilities that are affordable, effective and that offer a strategic-edge, maintaining a credible and sustainable defence force is challenging, as Europe is now discovering. The European Defence Technological Industrial Base (EDTIB), while relatively young and subject to political contestation between EU member states, has emerged as a response to Europe’s defence-industry strains. Many, including the EU’s High Representative Catherine Ashton, see the EDTIB as a necessity from a strategic and economic point of view. It aims over the longer-term to integrate national defence-industrial bases.

However, both Europe’s defence markets and the nascent EDTIB are open to international competition in the form of non-EU Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), foreign mergers and acquisitions and shareholdings. FDI in Europe’s defence industrial infrastructure (naval ports, arms-producing factories, etc.) from countries outside of the EU – an issue encouraged by the Eurozone crisis – has given policy-makers the unenviable task of balancing the need to re-structure Europe’s defence industry while also maintaining defence autonomy.

Privatising defence-industries and selling them off to third-countries through FDI deals – in many cases to strategic competitors – has emerged as a way of taking the pressure off of sovereign budgets. But getting these defence-industrial assets off the sovereign budget books entails long-term consequences. The problem is not just about the expansion of defence productive capabilities in third-countries, but also the transfer of high-tech military knowledge and the classified information and procedures that are in some cases embedded in productive processes.

Of course, given the European single market, there can be no serious objection to defence FDI by other EU states. Indeed, this may boost European defence-industry integration. But allowing FDI by foreign, state-owned companies – as is principally the case with Chinese firms – is another issue. While overall inflows of inbound FDI into the EU have decreased since 2007, it has been estimated that in 2011 China’s major FDI assets in the EU included $253 million (US) in aerospace, defence and space and $1.357 billion in communications, equipment and services, also linked to the defence sector.

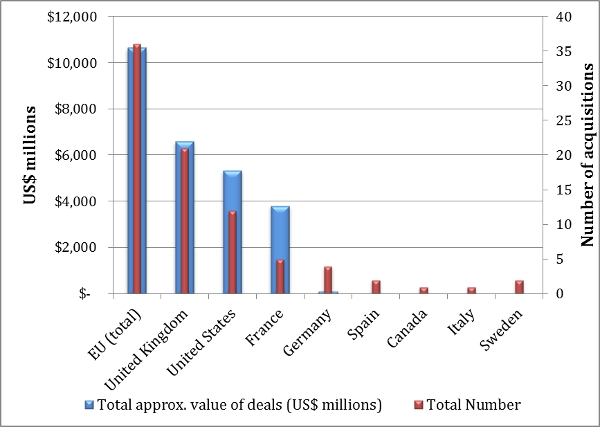

True, from 2007-2009 most defence FDI principally came from within the EU (36 defence companies were acquired by other member states over this period), then the United States (buying 12 defence companies), with the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) not featuring, as shown in Figure 1. However, the proposed sale of Greece’s Hellenic Defence Systems and Portugal’s Viana do Castelo shipyard, plus the actual sale of Deltamarin (a Finnish naval shipbuilding yard) to China’s state-owned Aviation Industry Corporation for $51 million in October 2012, should give pause for thought.

Figure 1 – Acquisitions of EU-Based Arms Producing Companies, 2007-2009

Source: SIPRI.

So what is being done at the European level to supervise such defence-industry sell-offs? In short, there is no European coordination between the member states on defence privatisation or FDI. Screening of defence FDI is fragmented at the national level. Only ten EU member states have national FDI restrictions in place: Lithuania and Slovenia have outright bans; prior approval is required in Austria, Denmark, Poland, Spain and Sweden; and a review is conducted in France, Germany and the United Kingdom. The rest have no formal policies that protect their respective defence industries from non-European FDI.

This is odd given that countries such as Australia, Canada, China, Japan, Russia and the United States (US) do unashamedly vet defence FDI. The US Treasury Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), for example, will stop non-American FDI investments if there is a risk that defence infrastructure will be used to restrict supplies to the US government, to initiate technology transfers or for sabotage. Europe could initiate a similar system. True, the EU will want to retain a degree of trade and market openness, but the European Commission could use its exclusive competence in FDI to start a debate among the member states. An outright prohibition on defence FDI would not work, as the EU would be accused of protectionism. An approval process for such FDI would be accused of being too arbitrary. Given the present disparities between national systems in the EU, and the inconsistency this causes, the best possible framework would be a European-level review process for all non-EU defence FDI supervised by the European Commission.

The member states must realise that maintaining critical defence infrastructure is the bedrock on which to build an efficient European defence market that works. Just as mutual fiscal surveillance is increasingly becoming important in Eurozone governance, so too is it time for some degree of supervision to emerge for the benefit of Europe’s nascent defence-industrial base. Selling-off critical defence infrastructure in one member state has a European-wide security impact. The best case scenario is that the EU puts in place a common defence FDI supervisory framework, but if not, at least discussing the issue at the European level may serve to improve national systems that do or do not exist.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics, nor of the Institute for European Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/14tE6GH

_________________________________

About the author

Daniel Fiott – Institute for European Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Daniel Fiott – Institute for European Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Daniel Fiott joined the Institute for European Studies in September 2012 as a Doctoral Researcher with the European Foreign and Security Policy research cluster. At the IES, Fiott’s Ph.D. research project looks at European defence-industrial integration with a focus on the political evolution of the nascent European Defence Technological and Industrial Base. His other research interests include the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy more broadly, the Common Foreign and Security Policy and International Relations theory, with a special focus on realist thought.

1 Comments