A provisional EU agreement has been reached on the principle of capping bonuses in the European banking industry. Kent Matthews and Owen Matthews present a case for maintaining bankers’ bonuses, arguing that there is no causal link between bonuses and excessive risk-taking. They state that the real cause of risk-taking is the widespread policy of bailing out banks which are deemed ‘too big to fail’, and that capping bankers’ bonuses might simply drive business away from Europe towards other global financial centres.

A provisional EU agreement has been reached on the principle of capping bonuses in the European banking industry. Kent Matthews and Owen Matthews present a case for maintaining bankers’ bonuses, arguing that there is no causal link between bonuses and excessive risk-taking. They state that the real cause of risk-taking is the widespread policy of bailing out banks which are deemed ‘too big to fail’, and that capping bankers’ bonuses might simply drive business away from Europe towards other global financial centres.

The European Parliament is misguided in thinking that a cap on bankers’ bonuses will reduce risk-taking and tilt the banking industry back to the boring banking world of Captain Mainwaring. The argument is based on the simplistic notion that there is a positive relationship between bankers’ bonuses and risk-taking: therefore controls on bonuses will also control risk taking. The problem with this argument is that bankers’ bonuses are an effect and not a cause of excessive risk taking by banks. In other words, both compensation and risk taking are endogenous variables, driven by the widespread expectation that banks are ‘too-big-to-fail’ and will always be bailed out by the taxpayer.

In bailing out the banks, governments cemented the view that because of their size, influence, and nature, banks were too big to fail. To allow them do so would lead to a systemic risk which would quickly infect the entire banking system. There is perhaps some truth to this, but the unintended consequence of deeming banks to be too big to fail is that it actively encourages excessively risky behaviour. What incentive is there for a banker to exercise restraint when he knows that if the worst comes to the worst the taxpayer will step in?

What then is the solution? A ‘no bailout policy’, which would be the ‘first best’ case is ‘time inconsistent’. It lacks credibility because of the fundamental importance attached to the protection of depositors and the payment mechanism from systemic failure. Counter-cyclical capital requirements, deeper capital adequacy, higher liquidity ratios, ring fencing, lower leverage ratios and even downsizing are all regulatory measures that have been proposed in the Basel 3 measures and the Vickers Report. Caps on bankers’ pay are not part of this.

While the European proposal is superficially appealing to a banker-bashing electorate, the decision has been largely derided by commentators and industry experts, with London’s typically outspoken mayor describing the deal as “possibly the most deluded measure to come from Europe since Diocletian tried to fix the price of groceries across the Roman Empire.” Controls on pay for bankers will do nothing to address the risks its proponents are concerned about, and could end up damaging the most profitable square mile in the world. The economics of tax evasion and avoidance (sometimes referred to as ‘avoision’) provide clues as to the response of the industry. Discussions have already begun on the ways in which banks may seek to circumvent such rules, with the most popular suggestion being that they will increase salaries in order to retain the top talent. Doing so would not only diminish the link between pay and performance, it will substantially increase banks’ fixed cost base, reducing their competitive position and leaving them with less flexibility to reduce or claw-back bonuses when needed.

Raising salaries is also unlikely to be the banks’ only option. From generous housing allowances to devising loyalty payments, banks in London have a history of finding ways around payroll legislation they don’t like (in the 1990s some paid part of their employees’ salaries in gold bullion, diamonds and fine wines in a bid to avoid a form of payroll tax).

The UK, whose government is opposed to the current proposals, already has some of the most stringent compensation regulation in the developed world. The Remuneration Code, introduced in January 2010 and revised in 2011, applies to some 2,700 financial sector firms (and also applies to overseas branches of UK headquartered banks covered by the Code). Its provisions include requirements that at least 40 per cent of variable remuneration should be deferred for at least 3 to 5 years, that 50 per cent of variable remuneration is paid in shares or some other non-cash form, and that bonuses should include performance adjustment mechanisms to allow unvested awards to be reduced where there is evidence of employee misbehaviour or material error, or there is a material downturn in the financial performance of the firm. Anything more restrictive will play into the hands of competing financial centres such as New York, Hong Kong and Singapore.

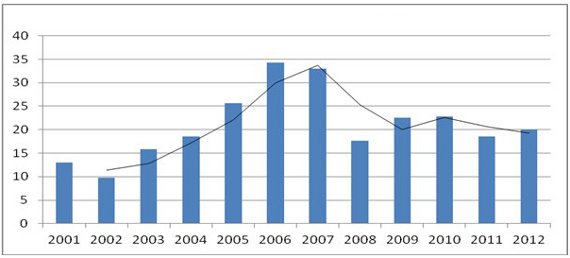

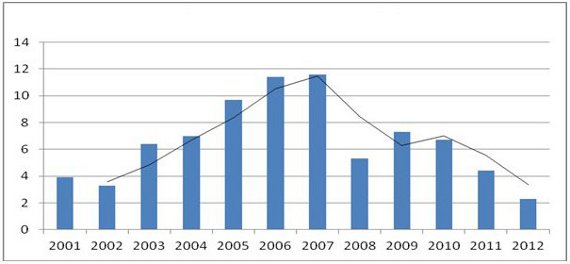

Figures published on bonus compensation (Figures 1 and 2) already show a clear divergence between the City of London and Wall Street since the onset of the financial crisis. While neither have returned to pre-crisis levels, London’s bonus pool has continued to shrink, whereas Wall Street variable compensation appears to have stabilised. A recent survey of UK banking professionals conducted by Hays recruitment showed 69 per cent of respondents were dissatisfied with their bonuses, and 34 per cent of them were looking to leave their employers because of their bonuses falling below expectations. Such evidence lends further support to the argument that over the longer term London’s coveted position as a global financial epicentre will continue to be eroded as bankers vote with their feet and move to jurisdictions with fewer restrictions on pay.

Figure 1: New York (Wall Street) Bonuses ($ billion)

Source: New York State Comptroller

Figure 2: London Bonuses (£ billion)

Source: Centre of Economics and Business Research

Figure 1 shows a stabilising of total bonus payments in New York, but the level is still well below the peak of 2006-7. The hard line is the two-year moving average which indicates the trend development. Figure 2 shows the total bonuses for London, illustrating a clear downward trend. This downward trend in London is a result of restructuring in response to anticipated regulation. The scaling back of bonuses is consistent with the research of Phillipon and Reshef. They find that financial deregulation and corporate activities linked to IPOs (initial public offerings) and credit risk increase the demand for skills in financial jobs, which in turn drives the earnings and bonuses of financial sector workers.

The impending regulatory environment has affected banking behaviour and bank lending (whether this is a desirable outcome in the current economic climate is another matter). Banks that were a few years ago posting returns on average equity targets of 25 per cent, are now targeting more modest returns of 10-15 per cent. However, the banks will still need financial market specialists to generate returns in individual profit centres, even if overall profits are down or even negative, and these specialists operate in a competitive labour market.

Bankers have been singled out as the principal villains in the blame game of the great recession, but in reality they were only a link in a long chain of villains starting with Western central banks and regulatory agencies, and ending up with highly leveraged households and firms. The link between pay and risk taking in banking is an established empirical fact, but the bottom line is that pay does not cause risk taking. Regulation can mitigate some of the risk taking generated by the creation of ‘too big to fail’ policies. Caps on bankers’ pay will at a minimum create market distortions, deadweight losses through avoision schemes and be welfare inferior. In the worst case, it will drive business away from Europe and do nothing to protect us from the next banking crisis.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/15xdGEp

_________________________________

Kent Matthews – Cardiff University

Kent Matthews – Cardiff University

Kent Matthews is a graduate of the LSE and the Sir Julian Hodge Professor of Banking at Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University. His research is in the area of bank deregulation, banking performance and competition in emerging economies.

–

Owen Matthews – Deloitte LLP

Owen Matthews – Deloitte LLP

Owen Matthews is a graduate of LSE and is a former City Solicitor now working in restructuring services at Deloitte LLP.

4 Comments