What determines a country’s bargaining success when negotiating EU legislation? Using data from legislative proposals negotiated between 2004 and 2008, James P. Cross assesses the impact that direct intervention in the decision-making process has on outcomes. He finds that those states which voice disagreement over Commission proposals most often tend to have the least bargaining success.

What determines a country’s bargaining success when negotiating EU legislation? Using data from legislative proposals negotiated between 2004 and 2008, James P. Cross assesses the impact that direct intervention in the decision-making process has on outcomes. He finds that those states which voice disagreement over Commission proposals most often tend to have the least bargaining success.

A number of recent EUROPP contributions have considered the different factors that determine the winners and losers in legislative negotiations in the EU. Jonathan Golub considered member state bargaining success and argued that smaller states do comparatively better than larger states. Stuart A. Brown argued that the success of smaller member states in affecting the negotiation process might be because they take positions closer to potential winners in the first place.

Neither author considers the actual process of negotiation itself, which starts with the initial positions of member states, and ends with final policy outcomes. This intermediate stage of negotiations is key in determining legislative outputs, as it is exactly when member states can argue for their policy positions in attempts to affect policy outcomes in their favour. To be fair to both authors, they do not have the data necessary to examine this stage of the negotiation process, but careful consideration of negotiator activities during the negotiation process is none the less required to fully understand who wins and who loses in EU negotiations. This post aims to add to the debate surrounding winners and losers in the Council by considering whether member states can actively affect their bargaining success through direct intervention during the negotiation process.

My own research uncovers how negotiators behave during negotiations. I combine data on member states’ initial positions and final policy outcomes with a measure of the amount of interventions each member state makes over the course of negotiations. An intervention is defined as any explicit statement of disagreement with the Commission proposal at a particular point in the legislative process. These interventions are made by a member state at official meetings in Council working groups and in the Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER) over the course of negotiations for a particular proposal. They are important, as they act as a signal to other negotiators that a member state is dissatisfied with a particular part of the proposal and would like to see it changed.

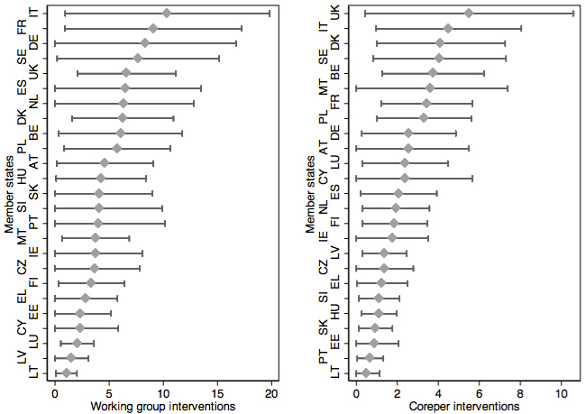

Figure 1 shows the total number of interventions made by each member state at the working group and COREPER levels within the Council for 16 legislative proposals decided upon between 2004 and 2008. Two things stand out here. Firstly, larger member states tend to intervene more than smaller member states. This more assertive behaviour is perhaps not surprising, given that larger member states will usually represent a larger cross section of domestic interests. Secondly, there seems to be a divide between older and newer member states, with those member states that joined the EU in the 2004 enlargement intervening less than older member states. This might be due to the fact that newer member states were finding their feet in the Council following the 2004 accession, and thus tended to intervene less.

Figure 1: Mean number of interventions at the Working Group and COREPER levels of negotiation

Source: Cross, J.P. (2012). Interventions and negotiation in the Council of Ministers of the European Union. European Union Politics 13(1): 47–69.

While it is clear from figure 1 that larger and older member states are more active than smaller and newer member states during legislative negotiations, a more important question is whether this intervention activity translates into legislative influence. Interventions might positively influence negotiations in favour of the intervenor, by influencing other member states to change their position and thus change the final outcome in the intervenor’s favour. On the other hand, interventions might be better characterised as a signal of dissatisfaction over the direction in which negotiations are headed, and are made when a member state sees thing are not going in their favour. Both interpretations of intervention behaviour are plausible, but we need to consider the relationship between interventions and legislative bargaining success to determine which more accurately describes their role in the negotiation process.

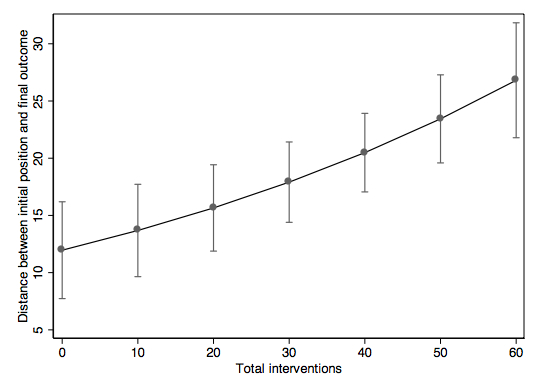

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the number of interventions made by a member state over the course of negotiations and that member state’s bargaining success. An increase in the distance between a member state’s initial position and the final outcome (y-axis) represents a decrease in bargaining success. As can be seen, there is a positive relationship between interventions and a member state’s distance from the outcome, suggesting that a member state that makes more interventions tends to have less bargaining success, and that interventions are a signal of discontent expressed by member states when negotiations are not going in their favour.

Figure 2: The relationship between interventions and member state bargaining success

Source: Cross, J. P. (2012). Everyone’s a winner (almost): Bargaining success in the Council of Ministers of the European Union. European Union Politics. 14(1) 70-94.

Some might see this as a surprising finding. The idea that more interventions imply less legislative bargaining success suggests that changing legislation through direct intervention is difficult. This in turn suggests that official Council meetings might be little more than a place where member states can register their discontent about expected policy outcomes, and the real negotiation determining legislative outcomes occur elsewhere. Indeed, when one watches the webcasts of Council meetings online, one gets the impression that negotiators are reading out pre-prepared statements rather than actually engaging in negotiation.

On the other hand, even if these official meetings represent a forum to publically state opposition to legislation through pre-prepared statements, this process itself can aid in holding decision makers to account. The fact that some public access is allowed to meeting records allows the public to monitor governments at the EU level. This potential for accountability is seen by many (but not all) as a good thing, and could in time lead to a more equal distribution of bargaining success across member states.

It is clear that further research into the manner that member states seek to influence legislative negotiation during the negotiation process is needed. A careful look at the content of interventions and their timing is appropriate, as the evidence discussed above does not account for these aspects of intervention behaviour. For instance, interventions relating to budget matters, sovereignty, and other salient issues are likely to have more influence than those relating to more technical issues. Similarly, one would expect that interventions made at the beginning of negotiations before consensus begins to form will probably be more influential than those made after significant progress towards agreement has been made. The above research represents a first step at uncovering these factors, but considerable work remains to be done.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/YVKdyk

_________________________________

James P. Cross – ETH Zürich & European University Institute

James P. Cross – ETH Zürich & European University Institute

James P. Cross is a post doctoral researcher in the European politics research group at the ETH Zürich, and a Max Weber fellow at the European University Institute. His research interests include EU decision making, EU institutions, comparative politics, and legislative transparency.