The success of Beppe Grillo’s Five-Star Movement in February’s Italian elections has focused attention on his use of the Internet as a campaigning tool. Duncan McDonnell argues that many of the techniques he has adopted, such as using social media in political communications, are not as revolutionary as they are often portrayed. The real innovation has been his and the movement’s use of the Internet to encourage grassroots co-ordination among activists at the local level.

The success of Beppe Grillo’s Five-Star Movement in February’s Italian elections has focused attention on his use of the Internet as a campaigning tool. Duncan McDonnell argues that many of the techniques he has adopted, such as using social media in political communications, are not as revolutionary as they are often portrayed. The real innovation has been his and the movement’s use of the Internet to encourage grassroots co-ordination among activists at the local level.

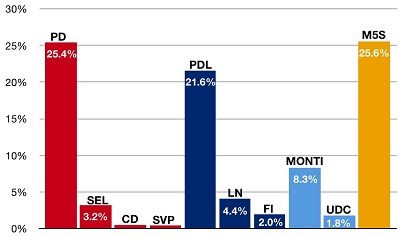

Close to nine million people voted for the Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S – Five-Star Movement) in the Italian general election on 24 and 25 February. More than anyone – pollsters, mainstream politicians and probably even Beppe Grillo himself – had expected. It was an extraordinary result. From under 5 per cent in opinion polls in early 2011, the M5S grew over the course of less than twelve months to take 25.6 per cent in the lower house of parliament (the Chamber of Deputies), thus becoming the single-most voted party in Italy. To put it in historical context: the M5S did better in its first general election than Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia did in its first one in 1994 (when it got 21 per cent of the vote). Figure 1 shows the vote share for each party in the Chamber of Deputies.

Figure 1: Party vote shares in the Chamber of Deputies

Notes: Parties in coalition are the same colour. Data based on that provided by the Ministero dell’Interno. It does not include the ‘Italians abroad’ and Valle D’Aosta constituencies.

The election result has provoked much media interest in the M5S and discussion of what type of political movement it is. However, the most common answer – that it is a new type of ‘Internet-based’ party dominated by its founder – is reductive. In fact, it is not so much Grillo’s use of the Internet per se at the national level that makes the M5S innovative, but how the online and offline are combined in its local organisation. Three points are worth making here about what is not so new about Grillo and the movement.

First, Grillo’s blog may have looked fresh and exciting when created in 2005, but it now appears quite dated both in its format and appearance. For example, there is no interaction between Grillo and those who comment on his posts. In this sense, we might say that Grillo ‘monoblogs’. Second, while the M5S organised online voting by circa 50,000 registered members on the movement’s national parliamentary candidates and its possible nominees for President of Italy, its use of the Internet to make decisions, whether on general policies or single issues, is still a long way from resembling liquid democracy platforms of the type advocated by the Pirate Party in Germany.

Third, although the idea that Grillo deploys social media in new and exciting ways in order to bypass traditional communication channels makes a good story, in reality he is not so different in this respect to other politicians. If we look, for example, at his Twitter account, we see that Grillo uses it fundamentally in the same ways as other Italian politicians: to tweet links to articles or statements that he has made elsewhere or details about his latest public rally. Simply having more followers than other politicians does not equate to a revolutionary use of social media.

So what is new then? In my view, the really innovative aspect of how the movement has used the Internet has been organisational, especially at the local level. In part through Grillo’s blog itself as a form of ‘shop window’ to recruit interested passers-by, but mostly via the use of meetup.com to create the Beppe Grillo meet-up groups which have formed the cornerstone of the movement’s presence across the country. In fact, Grillo has constantly encouraged his supporters to discuss – both on the Internet and in physical locations – the general issues he raises as they pertain to local questions in people’s own cities and towns.

On this point, it is worth noting that those activists I have spoken to all tell the same story of how they became involved: they began reading Grillo’s blog, then they checked the site of the local meet-up, then they started posting comments and participating in discussions on the meet-up’s forum. Sooner or later, they decided to go to a meeting – organised via the Internet, but held in a real physical location in their town – and thereupon joined in the local offline activities of the movement. For M5S activists, the Internet therefore does not simply replace face-to-face contact: it facilitates and complements it.

While innovative and, so far, very successful, the organisational model of the M5S also brings a series of challenges for the movement, especially given its spectacular emergence at the national level. Local activists focus on local issues, such as urban planning, environmental concerns, public utilities and decisional transparency. Activists join because – irrespective of their ideological backgrounds – they agree that these particular issues present problems and they believe that the other parties are at best incapable or, at worst, corrupt in their management of them.

However, given the movement’s general election result, all sorts of potentially divisive questions have now been created. For example: should the M5S provide a vote of confidence for the centre-left in order to help them form a government? Or what is the movement’s position on membership of the euro, or on immigration policy? There may be very different views on these issues among its activists and voters given the ideological heterogeneity and different political backgrounds present in both groups, particularly – but not only – the latter.

Organisationally, the M5S also has to face the question of the role of Grillo who, until now, has been the ‘national’ face of the movement while the grassroots busied itself with the local level. The M5S needs to prove to its detractors that it is not another personal party, in a country well used to personal parties such as those of Silvio Berlusconi. To do so, it must find a way of linking the grassroots to the new national level, which currently seems to be almost entirely in the hands of the leader. To put it in political science terms (which the movement would probably abhor), the M5S needs to join the dots between the party in public office, the party in central office and the party on the ground.

Sudden and enormous electoral success brings sudden and enormous organisational challenges. The M5S has so far shown – at least at the local level – that it is capable of finding innovative solutions in this respect. If it is to become a lasting force nationally, however, it will need to find more.

This article first appeared on EUDO café.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/14JAeVU

_________________________________

About the author

Duncan McDonnell – European University Institute

Duncan McDonnell – European University Institute

Duncan McDonnell is Marie Curie Fellow in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the European University Institute in Florence. He is the co-editor of Twenty-First Century Populism (Palgrave, 2008), the 2012 ‘Politica in Italia/Italian Politics’ yearbook and has recently published on the Lega Nord, Outsider Parties and Silvio Berlusconi’s personal parties. He is currently working with Daniele Albertazzi on a book entitled ‘Populists in Power’ which will be published by Routledge. He tweets at @duncanmcdonnell.

3 Comments