The past two decades have seen a massive rise in the number of foodbanks in Germany, often linked to the country’s welfare reforms. But what are the consequences of foodbanks, beyond simply helping those in need? Stefan Selke argues that the foodbank movement is in fact a backwards-looking policy that sees the solution to social problems in local neighbourhoods, and replaces structural attacks on the causes of poverty with the symbolic relief of its consequences.

The past two decades have seen a massive rise in the number of foodbanks in Germany, often linked to the country’s welfare reforms. But what are the consequences of foodbanks, beyond simply helping those in need? Stefan Selke argues that the foodbank movement is in fact a backwards-looking policy that sees the solution to social problems in local neighbourhoods, and replaces structural attacks on the causes of poverty with the symbolic relief of its consequences.

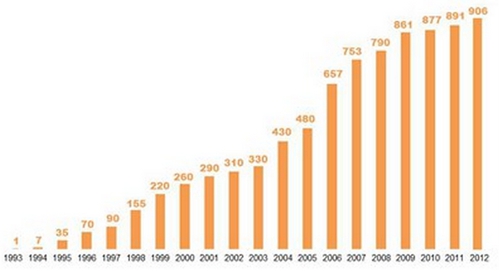

In 1993 the first foodbank (“Tafel”) was founded in Berlin. In the past 20 years, the number of foodbanks in Germany has grown to more than 1,000, as shown in Figure 1 below. Now, over 50,000 volunteers across Germany are involved with the collection of wasted food from supermarkets, which is then offered to the poor by local organisations. In the past 20 years foodbanks in Germany have been able to extend the range of their users considerably, and now provide more than 1.5 million people (from children to senior citizens) with food.

Figure 1 – Growth in number of foodbanks in Germany, 1993 – 2013

Source: http://www.tafel.de/die-tafeln/zahlen-fakten.html

Source: http://www.tafel.de/die-tafeln/zahlen-fakten.html

The main growth of foodbanks in Germany began 2005, when Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s government introduced the “Agenda 2010” of tax cuts, and cuts to pension and unemployment benefits. Around the same time, a new form of unemployment insurance (“Hartz IV”) was introduced, reducing previous benefit levels and the duration for which they can be received. In recent decades hardly any other phenomenon has become more prominent in the public consciousness, with the foodbank movement being seen largely uncritically and usually celebrated as a success. However, the first research projects (e.g. the “Tafel-Monitor” at the Furtwangen University, managed by Stefan Selke) into Germany’s foodbanks present paradoxes, discrepancies and consequential costs for those affected and for society as a whole.

The current situation

Despite their large number, one can observe regional disparities between the distribution and the accessibility of foodbanks (the supply side) and the distribution of poverty (the demand side). Until now, there has been no independent data set about the structure of foodbanks, the socio-demography of the users and (often overlooked!) about those who refuse to use foodbanks.

By now, the practice of foodbanks has been examined in qualitative research projects. We know that those that use foodbanks are being placed into a vulnerable situation with both physical and psychological stress factors. The physical causes of stress include queuing in public and long waiting times. In interviews the psychological stress factors named repeatedly were fear (of being seen by others), embarrassment, restrictions (no choice, no right to complain) and duties (statements of gratitude, rituals of submission). However, the main stress factor is shame. There is a fundamental conflict in that. Voluntary involvement is seen, on the one hand, as socially desirable while, at the same time many emotionally stressful experiences of shame and denial are accepted and socially permitted by foodbank volunteers.

The system of foodbanks is centred on questions of the legal form of foodbanks, the standards of food distribution and the rules concerning access and use. Users of foodbanks often perceive those rules as restrictive, discriminating and stigmatising. The distribution of donations of food by private persons within a volatile system (i.e. without guarantees, and dependent on numerous factors such as the amounts of food, personal feelings etc.) is diametrically opposite to the German constitution’s criterion of unconditional help in the context of an institutionalised system of solidarity in a welfare state.

Social contexts

Foodbanks are a controversial issue in Germany. They make conflicts of social policy visible, that have continued to be latent for the last 20 years. The mobilising and activation of civic participation means a shift from state guarantees to merely voluntary or honorary activities. As seen by many critics, this makes the foodbank movement a prototype for a backwards-looking policy about poverty and society, that sees the solution to social problems in local neighbourhoods and replaces structural attacks on the causes of poverty with symbolic relief of its consequences.

Moreover, the modification of the foodbanks’ basic legitimacy within a great alliance of “food saviours” is striking. Foodbanks have moved beyond being simply a social strategy (help for the homeless and poor) and are increasingly adopting an ecological strategy within which they stylise themselves as an environmental movement. However, foodbanks are neither social nor sustainable, at least, when sufficiently refined definitions of social sustainability are used, not taken from companies’ internal Corporate Social Responsibility ‘guidelines’. The causes of poverty cannot be fought with donations of food. Reducing the over-supply of food does not lead to a reduction in the amount of poverty.

Poverty as a commodity

Meanwhile, foodbanks in Germany have become a brand. They profit from their positive connotations by with an enhanced image, which they pass on to industry partners and sponsors. Foodbank users however, consider them to be a symbol of their own social exclusion and unrealised participation in the majority of society. Foodbanks have become established as a firm system that deals with social matters using economic criteria (expansion, market share, growth, efficiency, synergies etc.); 20 years of foodbanks are the irrefutable evidence for that. They indicate the failure of politics, that firstly produces “poverty made in Germany” and then exports it into a private volunteer system. Here, it is less and less a matter of fighting poverty sustainably, because it is profitable to too many who recognise poverty as a commodity and draw benefit from it. Foodbanks are a part of such a market in which symbolic and economic profits can be achieved from poverty. For example, businesses increasingly use Corporate Social Responsibility actions as a substitute for taking on real social responsibility. They replace payments of tax, minimum wages and other compulsory actions.

Emergency solution instead of long-term solution

It is becoming simpler and more normal in Germany to receive public approval for voluntary relief of poverty than political legitimacy for combating the roots of poverty. The offerings of foodbanks are only the short-term alleviation and management of poverty. The danger behind this is an indirect (and unintended) stabilisation of poverty because the tasks of the state are more and more being delegated to supported employers, subsidised agencies and private players.

A society should be judged by how it deals with its weakest members. Foodbanks still have their reason for existence as an emergency solution for those in need, but not as an institutionalised long-term solution. This assertion marks both the fundamental boundary shift of the past 20 years and the task of a new orientation. It would be regrettable if foodbanks were to lead only to socially well arranged needs for many. The question is therefore not whether voluntary commitment makes sense, but where and how it is appropriate.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/12lTfWT

_________________________________

Stefan Selke – Furtwangen University

Stefan Selke – Furtwangen University

Professor Stefan Selke is professor of sociology and social change at the Furtwangen University in Germany. Foodbanks have been his research field since 2006. He has published five books and numerous arcticles on different aspects of foodbanks. As a public sociologist he often appears in the media. Currently he manages the research project “Tafel-Montor“ about foodbanks in Germany.

Food banks in any wealthy country are a disgrace and all politicians in those countries should be ashamed that their policies have led to this.

In every single policy that I have read that comes out of the EU, there is a very glaring omission. None of the policies mention anything about ‘the people’. The EU is concerned only with methods of making money by whichever method they can – the people are of no consequence except to do the work to create profit.