Participation in electoral politics has declined across Western Europe in recent decades as citizens have become increasingly disillusioned with conventional forms of politics. As James Sloam notes, this is especially true for the current generation of young Europeans, who have turned to alternative forms of political engagement that seem to have more relevance to their everyday lives. Indeed, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, we have witnessed a resurgence of youth political protest. The hallmark of young people’s politics is ‘diversity’: a wide array of participatory acts performed across hybrid public spaces (from Twitter to the town square). But we must also be concerned with ‘who participates’ – in particular the large social inequalities inherent in non-electoral forms of engagement.

Participation in electoral politics has declined across Western Europe in recent decades as citizens have become increasingly disillusioned with conventional forms of politics. As James Sloam notes, this is especially true for the current generation of young Europeans, who have turned to alternative forms of political engagement that seem to have more relevance to their everyday lives. Indeed, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, we have witnessed a resurgence of youth political protest. The hallmark of young people’s politics is ‘diversity’: a wide array of participatory acts performed across hybrid public spaces (from Twitter to the town square). But we must also be concerned with ‘who participates’ – in particular the large social inequalities inherent in non-electoral forms of engagement.

Participation is a cornerstone of citizenship in liberal democracies. Yet most European democracies are today characterised by low or falling voter turnout and the dramatic decline and ageing of political party memberships. These trends are most striking amongst young people (defined here as 15 to 24 year olds), who have become alienated from mainstream electoral politics in established European democracies.

Nevertheless, there is overwhelming evidence to show that young people are not apathetic about ‘politics’ (in a broader sense) – they have their own views and engage in democracy in a wide variety of ways. Indeed, it is young people themselves who are diversifying political engagement: from consumer politics, to community campaigns, to international networks facilitated by online technology; from the ballot box, to the street, to the Internet; from political parties, to social movements and issue groups, to social networks. Indeed, the slow-burning participatory crisis in democratic politics has become transformed by the global financial crisis into a new wave of youth protest, from Cairo, to Madrid, to New York, to Istanbul to Rio de Janeiro.

Today’s young people can be portrayed as ‘stand-by citizens’. They have a preference for intermittent, non-institutionalised, horizontal forms of engagement on issues that have relevance for their everyday lives. In this context the proliferation of protest politics amongst young Europeans – faced with a hostile labour market and austerity budgets that have reduced spending on education and youth services – is hardly surprising. 2011 was the year that many young people rose up and overthrew their leaders in North Africa and the Middle East (the so-called ‘Arab Spring’). Youth activism also became a major feature of European politics: from mass demonstrations of the ‘outraged young’ (the ‘indignados’) against political corruption and youth unemployment, to the Occupy movement against the excesses of global capitalism, to the emergence of new political parties promising a new style of citizen-centred democracy (such as BeppeGrillo’s Five Star Movement in Italy or the German Pirate Party).

However, these young activists predominantly come from privileged backgrounds. Socially excluded young people have sometimes expressed their frustration and lack of hope through political extremism and violence, as illustrated by the rise in support for nationalist parties (such as the National Front in France and Golden Dawn in Greece) and riots that have shaken several European countries (including the UK and Sweden) in recent years.

In one sense, young people’s politics remains vibrant, as repertoires of participation have become more diverse – a further realisation of Pippa Norris’ ‘democratic phoenix’ thesis. On the other hand, the fact that (in Europe) these alternative forms of engagement are much less socially equal than voting (see my Table below) is troubling.

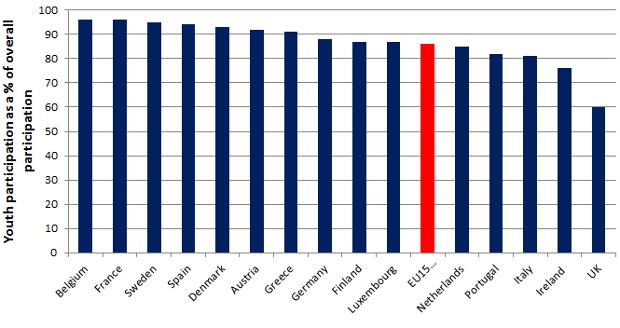

An analysis of European Social Survey data for the old EU15 highlights the diversity of participation. My Table below compares voting to some of the more common non-institutionalised forms of engagement (often grouped together as ‘protest politics’). For young Europeans, voting is the most popular form of participation – 59 per cent of those eligible to vote claimed that they had done so in the previous parliamentary election (compared to 82 per cent for the general population) – but youth participation is more evenly spread across different forms of participation than is the case for older generations. Unlike voting, the four alternative forms of participation are as popular or more popular amongst young people in comparison to the population as a whole. However, the ratio of youth participation varies significantly across these four activities. In particular, the more overt forms of protest (displaying a badge or sticker, taking part in a demonstration) are dominated by the young.

Table: The proportion of people who undertook five main types of political engagement across the EU15 countries (Blue numbers are for the overall population, red for young people aged 15 to 24)

Source: European Social Survey cumulative data (waves 1 to 4, 2000-2008)

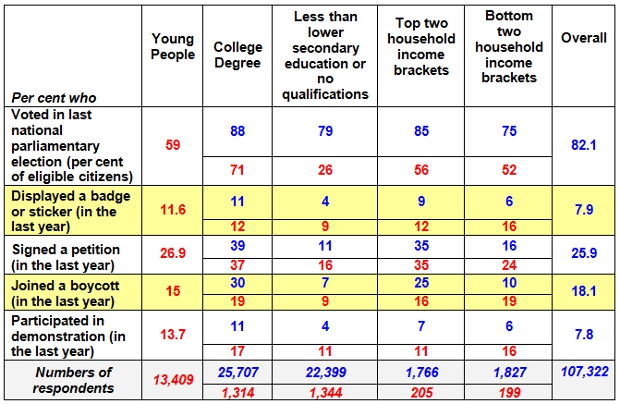

Despite these common trends, youth participation is strongly related to a country’s civic culture. In countries where certain forms of engagement are relatively high for all ages – for example, demonstrations in Spain and petitions in the UK – this is usually the case for young people too. And, youth participation as a proportion of the general population is relatively constant. In thirteen of the EU15 states, young people participate at between 81 per cent and 96 per cent of the rate for all ages (see my Chart below). The main outlier is the UK, where the proportion of youth participation falls to 60 per cent (I discuss the comparative weakness of youth participation in the UK in a recent issue of the PSA’s Political Insight magazine).

Chart: Youth participation rates as a percentage of the participation rates for all citizens in each of the EU15 countries

Note: Eight activities were included in calculating total participation rates: ‘voting in last national election’, ‘working for a party or action group’, ‘working for another [political] group association’, ‘displaying a badge or sticker’, ‘signing a petition’, ‘joining a boycott’, ‘participating in a demonstration’

Source: European Social Survey cumulative data (waves 1 to 4, 2000-2008)

The Table shows that socio-economic status (here, educational attainment and household income) is a more important indicator of engagement in non-electoral forms of participation than it is for voting. This is certainly a cause for concern when it comes to youth participation. However, my Table also suggests, counter to expectations, that social inequalities are reduced for young people in these alternative forms of participation (even though they are increased for voting) in comparison to older generations. There are at least two explanations for this interesting phenomenon. On an optimistic note, it could reflect the ‘normalisation’ of these alternative forms of participation across social groups over time. Second, it suggests that institutions matter. There is evidence to show that being in school or university matters more than levels of educational attainment in predicting political participation. In other words, educational institutions have the potential to neutralise social inequalities in participation.

The evidence demonstrates that, behind the common trends in youth participation, we are witnessing a diversification of political engagement in terms of how young people find political voice and which young people find political voice. However, the gap between youth turnout and overall turnout in national elections is problematic. The ageing of European populations means that 18 to 24 year olds are a shrinking group in European electorates. If only a small proportion of this shrinking group votes, politicians will pay little heed to young people’s interests, leading to further disillusionment. And, the vicious circle continues. A further symptom of this malaise is the lack of contact between young Europeans and the people who make the decisions that affect their lives. In the EU15, contact between young people and politicians or officials is about half the rate of the population as a whole.

Clearly, politicians and public officials have much work to do if they are to engage effectively with today’s young Europeans. Efforts to interact with young people on issues of concern, including youth unemployment, might be a starting point. However, policy-makers should be aware that a mix of solutions is needed to reconnect with a socially, economically and politically diverse generation.

For a longer discussion of these issues, see two recent articles by James Sloam, in West European Politics and Comparative Political Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1aslEkJ

_________________________________

James Sloam– Royal Holloway, University of London

James Sloam– Royal Holloway, University of London

James Sloam is Senior Lecturer in Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London, where he is also co-director of the Centre for European Politics. His recent research has focused on the civic and political engagement of young people in Europe and the United States. He is also co-convenor of the Political Studies Association specialist group on young people’s politics and will be running a working group on this subject at the APSA Annual Meeting in August. If you are interested in joining this group and/ or participating in the working group in Chicago, please contact him at james.sloam@rhul.ac.uk He tweets about young people’s politics @James_Sloam

If you don’t vote – you don’t have a democracy. End of story. To suggest there are “other ways” to maintain a democracy beyond voting is a fallacy. If no one votes then you have a bunch of idiots complaining on their Tumblr blogs about an allowed dictatorship.