This book is about the global crisis and the right to resistance, about neoliberal biopolitics and direct democracy, about the responsibility of intellectuals and the poetry of the multitude. Using Greece as an example, Costas Douzinas argues that the persistent sequence of protests, uprisings and revolutions has radically changed the political landscape. This new politics is the latest example of the drive to resist, a persevering characteristic of the human spirit. By asking if another world is possible, Douzinas presents some hope that the rebellion against austerity is perhaps a sign of a more democratic and equitable Europe to come, writes Jia Hui Lee.

This book is about the global crisis and the right to resistance, about neoliberal biopolitics and direct democracy, about the responsibility of intellectuals and the poetry of the multitude. Using Greece as an example, Costas Douzinas argues that the persistent sequence of protests, uprisings and revolutions has radically changed the political landscape. This new politics is the latest example of the drive to resist, a persevering characteristic of the human spirit. By asking if another world is possible, Douzinas presents some hope that the rebellion against austerity is perhaps a sign of a more democratic and equitable Europe to come, writes Jia Hui Lee.

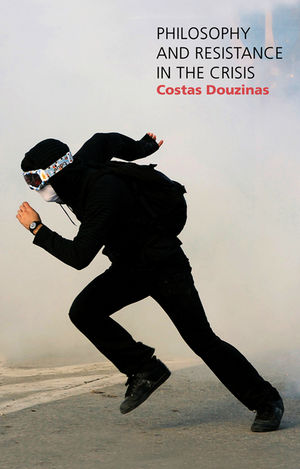

Philosophy and Resistance in the Crisis: Greece and the Future of Europe. Costas Douzinas. Polity. May 2013.

Philosophy and Resistance in the Crisis: Greece and the Future of Europe. Costas Douzinas. Polity. May 2013.

Philosophy and Resistance in the Crisis: Greece and the Future of Europe provides a meditative account of Europe’s current predicament. Costas Douzinas, a Professor of Law at Birkbeck, University of London, draws on philosophical works by Aristotle, Alain Badiou, Thomas Hobbes, and Slavoj Žižek, in an attempt to articulate a framework for addressing the recent sweep of mass uprisings, increasing xenophobia, and public cuts across the continent. Using the mass uprisings against austerity in Greece as a case study, Douzinas carefully examines the conditions that make our era one of resistance. The future of Europe, Douzinas argues, is a resistance that must bind together the “infinite encounters of singular worlds” (p. 208) and “learn again what it means to be at home with the other” (p. 207).

Douzinas opens Part I with a discussion of debt: the cause of the European crisis. He links the condition of indebtedness with an increasing consumerism enabled by technological developments in the finance industry (pp. 33-34). For Douzinas, the socio-political model that defines European states is neoliberalism, a “convergence of classical liberalism and social democracy” that retains a strong state to “uphold order and keep resistances in check” while “public utilities and social amenities” are being “privatised” (pp. 25-26). In order to achieve these aims, the neoliberal state has to manage its population by limiting its services, attacking immigrants in Greece who pose a ‘strain’ on the healthcare system under a campaign called ‘Hospitable Zeus’ launched by New Democracy, the centre-right Greek political party that came to power. The arrest of ‘foreign-looking’ sex workers who were detained pending trial and subjected to HIV tests is a grim emblem, Douzinas tells us, of the biopolitics of austerity (p. 42). The management of failure requires the forsaking of individual immigrants who must be incarcerated for the Greek population to survive.

Part II provides the philosophical background for thinking through the mass uprisings that forced Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou to resign in 2011. For Douzinas, the mass uprisings and electoral gains made by the Greek Coalition of the Radical Left, or Syriza, are the way out of Europe’s crisis. He wonders if the retreat of state sovereignty, prompted by capital mobility and an emerging global neoliberal consensus, means that Left politics must abandon its current privileging of singular (gender, racial, national, and class) identities for the “multitude” gathering in public squares to resist austerity. For Douzinas, resistance by the multitude brings together radical equality and democracy. The multitude, he says, may only understand exploitation and domination by embracing the excluded: “undocumented immigrants, the unemployed, [and] the poor” (p. 114). The resistance movement’s insistence on including conflicting constituents of power turns it into a “self-determining multitude” (p. 133) with the radical potential to create new forms of governance.

Part III charts the possibilities that a resistance by the multitude might offer. Douzinas particularly challenges Salvoj Žižek’s skepticism of mass uprisings. Žižek fears that a mass movement without direction or strong leadership would be easily incorporated into late capitalism’s “self-revolutionizing” project (p. 185), resulting in little fundamental changes to the systemic redistribution of wealth away from the poor. Douzinas counters however that Syriza’s electoral gains not only effectively bring together the militant and raw energy of a resisting multitude but is also motivated by a clear goal to reconfigure politics through parliamentary democracy.

In the Prologue, Douzinas admits that the book was written in a “short period” while the original Greek edition was written in “outrage and despair” (p. 4). Such emotions, coupled with haste, come through in Douzinas’ writings. His arguments are occasionally hard to follow and his discussions of critical theory and radical philosophy are often too cursory for a reader to fully engage. It is also easy to forget, in Douzinas’ fervent desire to bring together past philosophical reflections on the Left, what the thrust of the book’s arguments is. Douzinas would perhaps like to see the resisting multitude rise up and govern Europe, but it is unclear what that exactly means, or how it would work, given the diversity of contexts of austerity, let alone of Europe. And although Douzinas, who is critical of the European Union, calls for a “protest against meaningless European citizenship” (p. 208), he does not offer any insight into whether resistance means a Greek exit from the EU.

These assessments should not, however, devalue the significance of this book. Reading Douzinas’ book will be useful not only to those seeking to understand the anti-austerity protests that continue to rock Europe but also to those intent on pursuing current debates about the future direction of neoliberal economic governance. Douzinas’ writings form an exciting entry point into the critical theories that are coming to grips with the age we live in. By asking if another world is possible, Douzinas presents some hope that the rebellion against austerity is perhaps a sign of a more democratic and equitable Europe to come.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/134Nkaj

_________________________________

Jia Hui Lee – University of Cambridge

Jia Hui Lee – University of Cambridge

Jia Hui Lee is a postgraduate student in the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge. His research has focused on the relationships between neoliberal capital and sexuality, changing conceptions of gender across time and place, and international development. He is also working on developing community organising approaches through his work in the students’ union and in ethical investments. Read more reviews by Jia Hui.

Am I missing something here?

Greece is a hot and rather dusty country that needs to work really hard to deserve and maintain a successful modern way of life. It was been utterly mis-run for a long time, borrowing money that it can not now pay back.

Can someone explain what specific policies the likes of Žižek and the ‘resisting multitude’ in Greece plan to offer the tough Asian financiers as the people who need to be persuaded to invest funds to keep this idiotic situation staggering on? Won’t they be utterly baffled if not annoyed that with so many things going wrong in Europe we are still producing rambling irrelevant books about Leftist ‘critical theory’ rather than working flat out to do something practically useful?