A common theory is that voters are more likely to transfer their support to far-right political parties during periods of economic crisis. Cas Mudde argues that despite the widespread popularity of this idea, there is little evidence that Europe has actually experienced a shift to the far-right since the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008. He notes that more than a quarter of the EU’s 28 Member States have no far-right party of any standing, and of the countries which do have notable far-right parties, there is a fairly even split between those which have experienced an increase in support and those which have not.

A common theory is that voters are more likely to transfer their support to far-right political parties during periods of economic crisis. Cas Mudde argues that despite the widespread popularity of this idea, there is little evidence that Europe has actually experienced a shift to the far-right since the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008. He notes that more than a quarter of the EU’s 28 Member States have no far-right party of any standing, and of the countries which do have notable far-right parties, there is a fairly even split between those which have experienced an increase in support and those which have not.

Since the start of the Great Recession, the US subprime mortgage market crash that turned into a global economic crisis, it has become received wisdom that the far right is on the rise. How else could it be? Since the rise of the Nazis in Weimar Germany conventional wisdom holds that economic crises breed far right success. While there is no elaborate academic theory underlying it, the economic-crisis-breeds-extremism thesis might be one of the most popular social science theories out there today (together with the closely related modernisation theory). It is received wisdom among academics, journalists, and policy makers alike.

The idea that the Great Recession fuelled a resurgence of the far right, i.e. both radical and extreme right parties, is based mostly on two highly publicised cases, both in 2012: the National Front (FN) in France and Golden Dawn in Greece. Having finally replaced her father, party founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine Le Pen took the FN as a phoenix from the ashes. After years of electoral decline, she led the party to its best ever results in the presidential and second best ever results in the parliamentary election of 2012. Even more shocking were the two Greek parliamentary elections in May and June 2012, which saw the entrance of the, until then marginal, neo-Nazi Golden Dawn into the Greek parliament. While many radical right parties have entered national legislatures since 1980, this was the first time that an openly extreme right party was able to pull it off. For most observers, academic and non-academic, these two cases were symptomatic of the rise of the far right in Europe, the expected result of the economic crisis.

An analysis of the recent electoral results of far right parties in EU member states shows a very different picture, however. If we compare pre-crisis results (2005-2008) with results during the crisis (2009-2013), the striking lack of electoral success of the far right stands out most. First of all, more than one quarter, eight of the twenty-eight, current EU member states have no far right party to speak of. Interestingly, this includes four of the five bailout countries (Cyprus, Ireland, Portugal and Spain); Greece being the only exception.

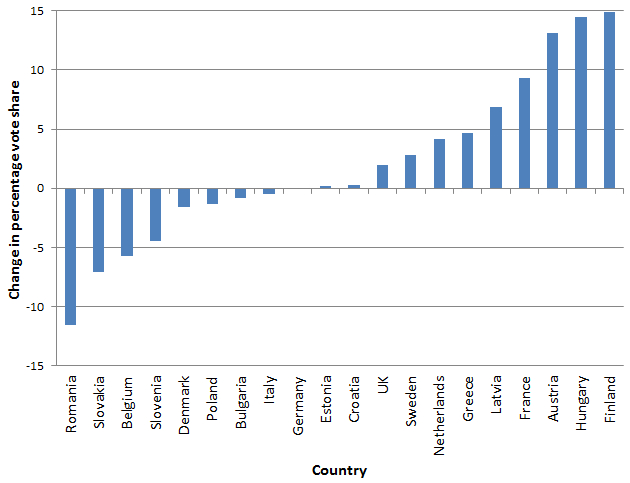

Second, among the twenty countries with (somewhat) relevant far right parties, the electoral results are almost evenly split: eleven have seen an increase in electoral support for far right parties during the period 2005-2013, and nine have not. Third, of the eleven countries with rising far right support, only five saw more or less sizeable increases in absolute (rather than relative) terms. However, against these five countries in which far right parties gained more than five per cent of the vote between 2005 and 2013, stand three countries that saw a decrease by more than five per cent (Belgium, Romania and Slovakia). My Chart below illustrates the results.

Chart: Change in percentage vote share for far-right parties in elections before (2005-2008) and during (2009-2013) the financial crisis

Note: The chart shows changes in percentage vote shares for far-right parties from the last national election held before 2008 to the most recent national election (as of August 2013). In most cases the comparison is based on the vote share for a single party in each election, however in certain cases the figure is an aggregate change based on more than one party. Figures taken from European Election Database (EED).

The five EU countries that have seen a substantial rise of populist radical right electoral support are Austria (+13.1 per cent), Finland (+14.9 per cent), France (+9.3 per cent), Hungary (+14.5 per cent), and Latvia (+6.9 per cent). Greece comes close (+4.7 per cent), almost doubling its support, and will be discussed separately below. The single biggest increase is in Finland, where the True Finns jumped from 4.1 percent in 2007 to 19.0 percent in 2011. Interestingly, Finland was among the least affected EU countries, having faced its own economic crisis over a decade before the Great Recession. This notwithstanding, the economic crisis played a major role in the electoral campaign and success of the True Finns, who vehemently opposed Finnish participation in bailouts. That said, the populist radical right status of the party is heavily debated, and it seems at best a borderline case.

The other two West European countries, Austria and France, have both suffered rather moderate economic distress, unlike the two East European countries (Hungary and Latvia). And while there is no doubt that the parties have profited from political dissatisfaction related to the economic crisis, both the FN and the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) are established populist radical right parties, which have gained similar electoral results well before the crisis started (1997 and 1999, respectively). This leaves Hungary and Latvia, two of the hardest-hit countries in the former East, which as a region has not born the grunt of the Great Recession.

The rise of the Movement for a Better Hungary (Jobbik) has received significant academic and public attention, although it sometimes takes a backseat to the troubling policies of Premier Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz government. Jobbik won a staggering 16.7 percent of the vote in its first elections in 2010, replacing the marginal Hungarian Justice and Life Party (MIÉP) as the country’s premier populist radical right party. This was the second biggest increase after Finland. But where the True Finns might be too moderate to be considered populist radical right, Jobbik might be too extreme. It walks a fine line between radical right and extreme right, in part represented by the political party (Jobbik) and the paramilitary movement (Hungarian Guard). Although Hungary has been extremely hard hit by the economic crisis, and has been flirting with a bailout, the 2010 elections were not really fought over the Great Recession. While both Fidesz and Jobbik profited from widespread political dissatisfaction, its cause was partly economic (i.e. the economic crisis), partly political (i.e. the Gyurcsány scandal).

The most pure case of the economic crisis theory seems, oddly enough, the tiny and little noticed Baltic country of Latvia. Hit extremely hard by the banking crisis, Paul Krugman called Latvia “the new Argentina” in 2008. The fact that the populist radical right National Alliance (NA) has practically doubled its electoral support between 2006 and 2011 should therefore surprise no one. Moreover, following the Weimar scenario even more perfectly, the NA joined the Latvian government in 2011, although as a junior coalition partner. The puzzling aspect is, however, that the rise of the NA took place in 2011, after the peak of the economic crisis. While the economy nosedived in 2008-2009, the NA gained a mere 0.7 per cent in the 2010 elections (compared to 2006). Yet, after the economy stabilised in 2010, the party jumped from 7.7 to 13.9 per cent in the 2011 elections. That year, the Latvian economy showed a real GDP growth of 5.5 per cent!

In short, the numbers simply don’t add up. Despite all the talk of the rise of the far right as a consequence of the Great Recession, the sober fact is that far right parties have gained support in only eleven of the twenty-eight EU member states (39 per cent), and increased their support substantially in a mere five (18 per cent). Just as was the case during the Great Depression, i.e. Weimar Germany (and to a lesser extent Italy), the unfounded generalisation of a few high-profile cases (i.e. France and Greece) has obscured the fact that the vast majority of EU countries have electorally and politically marginal populist radical right parties, both before and during the Great Recession. At the end of 2013, only about half of EU member states have a populist radical right party in their national parliament, and only two in their national government, as junior partners (Bulgaria and Latvia).

This is not to say that the far right is irrelevant in contemporary Europe, or that the situation in Greece is not extremely troubling. Rather, it is a warning against selective perception and sensationalist generalisations as well as a call for keeping our eye on the real political threats of today. Throughout Europe politicians use the alleged threat of a far right resurgence, backed by the economic crisis thesis, to push through illiberal policies. A relatively moderate example is Greek premier Antonis Samaras’ increasing support for tough discourse on immigration and immigrants. An extreme example is Hungarian premier Orbán’s frontal attack on the country’s constitutional order. Both have defended their actions as necessary in the wake of mounting far right pressures, presenting their governments as the only realistic alternative to the far right hordes. And although both countries are indeed confronted with a particularly dangerous far right opposition, which is truly anti-democratic, neither party is even close to gaining political power.

In short, Europe is not at the brink of a Weimar Germany scenario. In sharp contrast to the situation in Weimar Germany in the early 20th century, extremists are relatively minor political players in the Europe of the early 21st century. Even more importantly, whereas the Weimar Republic was a democracy without democrats, democracy is hegemonic in contemporary Europe. It is important that Europeans remain vigilant toward the far right, but they should not get paralysed by an irrational fear, which can turn them into the uncritical masses of opportunistic and power-hungry ‘democratic’ political leaders.

This article also appeared at Policy Network

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/13RLni3

_________________________________

Cas Mudde – University of Georgia

Cas Mudde – University of Georgia

Cas Mudde is an assistant professor in the Department of International Relations at the University of Georgia. He is the author of Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe (2007) and co-editor of Populism in Europe and Latin America: Corrective or Threat for Democracy? (2012).

What if we remain critical on those so called “power-hungry ‘democratic’ political leaders” blaming them for extensive far-right leaning rhetoric (as for instance the anti-immigration speeches of samaras, or pasok ‘fence’ policies before). These so called power hungry democratic leaders are responsible for bringing far right ideas and terminologies back in the mainstream political space. Oh, and what a coincidence, this is quiet similar to how Hitler was introduced to the main political scene in Weimar democracy… what a coincidence.

Interesting articl, Cas. Have you also done a comparison of this with the changes in support for far right wing parties in other periods e.g. the 8 years before 2005, and the 8 years before that etc, to see if there are any similarities/differences in the distribution of change in support? That might be interesting of informative.

I agree, please present similar charts for 2000-2008 and 2000-2013!

Europe is walking a thin line, if the submissive left wing parties continue the way they do, people will give a quick rise to the far right. Happened before & will happen again. I don’t agree with Nazism but for people watching their beautiful countries being destroyed by African & Middle East Trash, It will be the only option.

I am afraid that you have completely missed out Russia and Ukrain. They are the first stopping point for anyone that is doing research on the subject.

This is a very interesting analysis indeed. To follow up on these results it would be interesting to figure out why we see an increase of right-wing politics in some countries, i.e. what they have in common. I have a feeling that one common denomnator might be (a perceived) inferiority complex of these countries. Austria, Hungary, and Finland for example all have larger neighbours to which they have to stand up to. Also France is still living the “grand nation” although this status was lost (or is at least fading) over the years. Together with the fact that these countries pay a significant amount (in comparison to other countries, i.e. think of the net contributor status) to the EU and for the fight against the crisis, I think something like an inferiority complex might play a role here. I believe this could be an interesting reasearch project that may help us to understand the EU, as complex international entitity, better. It would be interesting to hear other professional opinions about these thoughts.