On 22 September, Germany will hold federal elections. Philine Schuseil provides an overview of the potential coalitions which might emerge from the elections, and the policies of each of the major parties on Europe and the Eurozone crisis. Using recent opinion polls, she argues that the next German government is likely to be a ‘grand coalition’ between Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU and the SPD. Regardless of the coalition which comes into power, however, the country’s overall course on Europe is unlikely to change significantly, in no small part due to the institutional and public opinion constraints it will be forced to work under.

On 22 September, Germany will hold federal elections. Philine Schuseil provides an overview of the potential coalitions which might emerge from the elections, and the policies of each of the major parties on Europe and the Eurozone crisis. Using recent opinion polls, she argues that the next German government is likely to be a ‘grand coalition’ between Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU and the SPD. Regardless of the coalition which comes into power, however, the country’s overall course on Europe is unlikely to change significantly, in no small part due to the institutional and public opinion constraints it will be forced to work under.

Based on current polls, Angela Merkel looks likely to win a third consecutive mandate as Chancellor in September, and the chances of a non-Merkel government are very slim. Mrs. Merkel’s strong personal approval ratings and popularity are largely due to her handling of European policies. A large majority of Germans polled on those issues support Merkel’s gradualist approach toward the Eurozone crisis. Thus, the question is: which party will she govern with?

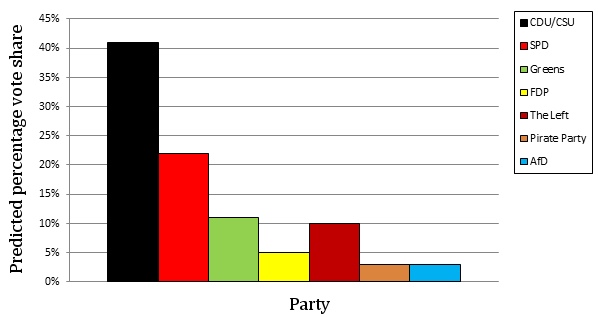

The German government is traditionally made up of two parties that form a coalition and control the majority of the government. A handful of smaller parties compete for the role of junior coalition partner. According to current polls, Mrs. Merkel would be able to choose between three potential coalition partners: her current junior coalition partner, the Free Democrats (FDP), the opposition Social Democrats (SPD) and the Greens. The Chart below shows the predicted vote share for each of the main German parties.

Chart: Predicted percentage vote share for 2013 German federal elections

Source: Forsa, 2013 (28.08.2013)

In a recent interview, Angela Merkel stated that “nobody is seeking a grand coalition”. However, she is not completely excluding the possibility. Indeed, a grand coalition (between the CDU/CSU and SPD) would have several advantages from her perspective. It would provide broad support for fundamental reforms in Germany and across Europe, and it seems to be favoured by a broad majority of the electorate. The main obstacle may be the Social Democrats, who fear a further weakening of their party. The SPD lost about a third of its voter support over the course of the last grand coalition with the CDU/CSU between 2005 and 2009. Concerns among party members had risen to such a degree that some backbenchers demanded that the party leadership formally rule out another grand coalition ahead of the election. This idea was, however, swiftly dismissed by party leaders. An SPD party convention, unusually held shortly after the September 22nd elections, will be crucial in deciding whether the SPD is willing to enter a coalition. In a grand coalition the Social Democrats would likely run finance, labour and foreign affairs, as they did between 2005 and 2009.

The CDU/CSU may have an alternative coalition partner in the shape of the Greens, who became an option after the government’s decision to speed up the phasing out of nuclear power as a reaction to the Fukushima disaster in Japan. But they remain far apart on quite a few key issues, especially after the Greens presented an election platform foreseeing tax increases. During the campaign, party leaders on both sides have also ruled out entering a ‘Black-Green’ (CDU/CSU and Greens) coalition.

It seems therefore that a centre-right coalition between the CDU/CSU and FDP, and a grand coalition are the most likely outcomes of the federal elections. Other scenarios seem less realistic: a Red-Green coalition (SPD, Greens) is mathematically impossible under the current polls, a Red-Red-Green coalition (SPD, The Left, Greens) has explicitly been ruled out by the SPD leadership, and a “Traffic Light” coalition (SPD, Greens, FDP) has been ruled out by the FDP leadership given irreconcilable differences between fiscal policies (the FDP has ruled out tax increases, while the SPD and the Greens are actively campaigning for them).

Party positions on Europe

The formal CDU/CSU election platform insists on the mantra of “solidarity in exchange for solidity”: i.e. structural reforms as a condition for giving financial aid to European partners. David McAllister, the Prime Minister of Lower Saxony, has outlined the party’s strategy as follows: “the CDU is strongly in favour of reducing the level of new borrowing and of strict adherence to national debt limits. We also want all EU member states to have balanced budgets and we call for the ECB to remain independent.” The CDU is opposed to any mutualisation of debt by introducing Eurobonds that would lead to a debt union (Angela Merkel has categorically ruled out Eurobonds during her lifetime.) Concrete reforms towards achieving a “union of stability” are: an effective European banking authority at the ECB for banks “too big to fail”, as well as insolvency procedures for banks, rigorous implementation of the rules of the tightened stability and growth pact and the fiscal pact with the possibility of sanctions, the drawing up of a rescheduling procedure within the Eurozone for nations no longer able to service their debts, and a closer coordination of policies on how to improve Europe’s competitiveness.

According to their programme, the Social Democrats aim at transforming the European Commission into a full-blown European government, elected and controlled by the European Parliament, and complemented by a second chamber representing national governments (the Council). They also aim to set up an economic government in the Eurozone to counterbalance the ECB, and to establish a ‘Social Stability Pact’ (e.g. EU minimum standards for social expenditures and minimum wages) to avoid social dumping within the EU. Last they would like to implement effective bank supervision: by the ECB in the short-term, and by an independent EU unit in the long term, with an additional resolution fund financed by the banking industry. The SPD election platform does not include a proposal for Eurobonds.

The FDP tends to be more critical on euro crisis management. Its party leaders call for a more cautious bail-out approach, even stricter conditionality, and advocate a change to the ECB’s voting rights (capital share-based voting weights and a veto for the Bundesbank) given the increasing importance of unconventional monetary policy. In their 2013 election platform, their main aim is to transform the currency union into a stability union, therefore insisting on strict adherence to the fiscal pact and opposing Eurobonds as well as a debt redemption fund. They do not want the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) to become permanent and favour the introduction of a sovereign debt restructuring mechanism.

Politically, the FDP aims to transform the European Parliament into a “full” parliament with rights to legislative initiative, and with the right to decide its location. The FDP would also like to change the Council into a chamber which has the same rights as the Parliament, and they advocate reducing the size of the Commission. In line with the programme of the CDU/CSU, they insist on the independence of the ECB and on the continuation of structural reforms in countries benefiting from EU financial aid. Furthermore, they propose the introduction of the German dual education system in other EU countries, and oppose European taxes under the principle of budget sovereignty.

The Greens, in contrast, support the German Council of Economic Experts’ proposal for a European Debt Redemption Fund and a substantial move towards a closer political union. This includes the election of the President of the Commission, strengthening the role of the European Parliament, and a substantial transfer of fiscal sovereignty as well as more federal control over national budgets. They also explicitly acknowledge that Greek debt is not sustainable and will require a haircut for public-sector creditors at some point in time.

In principle however, there is no real difference between the mainstream parties on European matters. SPD candidate Steinbrück and the Greens have often criticised the policy of Angela Merkel’s government, but have never argued for a radically different approach. Instead, they have voted in favour of all the rescue packages to date in the Bundestag. Moreover, opinion seems to differ more within the CDU/CSU and SPD than between them. The numbers of dissenters within the SPD – which mostly supports the government’s course in parliamentary decisions – almost equals that of their Conservative counterparts.

If anything, the SPD calls for more transparent Eurozone crisis management and for informing the public about the future “costs of Europe”. Greece is a case in point with the SPD openly talking about the need for another debt haircut – this time for the public-sector creditors – while the CDU is making this conditional on Greece achieving a high primary surplus in the medium term. For the time being, the party is working on other temporary solutions to meet Greece’s additional financing requirements. As a senior SPD official puts it: “We both want to stabilise the euro and the Eurozone, but the SPD is a bit more honest about what that will cost. “

Even regarding the most controversial issues (e.g. banking union, debt mutualisation), the positions of Angela Merkel’s government and the SPD only differ marginally. While the Merkel government is supportive of pillar one of banking union, namely a single supervisory mechanism, it has confined itself to advocating this for large banks only. It also supports a resolution framework for large financial institutions. It opposes, however, a common bank resolution fund and a joint deposit insurance regime. Steinbrück has clearly articulated that he favours a resolution fund financed by the industry, but also dislikes common deposit insurance. Mrs. Merkel is openly rejecting treating debt stock problems by mutualisation and she has ruled out euro bonds. The SPD tinkered with the idea of euro bonds and the bond redemption proposal by the German Council of Economic Experts, but finally avoided the matter as polls indicated the electorate’s lack of enthusiasm for ex-post risk sharing.

Only the Left party completely disagrees with Mrs. Merkel’s policy and has consistently voted in the Bundestag against bailout packages for other Eurozone countries. In their election platform the Left emphasises the idea that the crisis is not a debt, but a financial crisis: the rescue of banks caused the high levels of debts in Eurozone countries. In order to fight the (financial) crisis they favour a financial transaction tax of 0.1 per cent, the introduction of a bank levy, and the possibility of the ECB directly financing Eurozone central banks in a fixed framework (i.e. the creation of a European bank for public bond issues). Moreover, they demand a one-off charge on inheritances above 1 million euros, and a 75 per cent tax on high revenues for all EU Member states.

Impact of the elections on Europe and the crisis

Regardless of the future government, a major shift on key European issues is unlikely given factors other than the outcome of the federal elections. First, constitutional issues will likely constrain far-reaching political moves. Germany’s federal republic is marked by a plenitude of institutional checks and balances, including a very strong constitutional court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) protecting the Basic Law (Grundgesetz). During the Eurozone crisis representatives from both the ruling coalition and the SPD have challenged government decisions by appealing to the Constitutional Court. The Bundesbank has also presented objections before the Constitutional Court. Moreover, should EU leaders agree to call for another European Convention to revise the EU Treaty, which requires changes to Germany’s Basic Law, a referendum might become a realistic possibility.

Second, public opinion constrains far-reaching political moves since concerns of the German electorate over entering a so called ‘transfer union’ should limit the enthusiasm of MPs to approve ever larger bailouts. Note that the SPD would not be more lenient on the bailout question: it was the SPD who insisted on haircuts for Cypriot depositors.

Third, a continuation of the centre-right coalition would still have to negotiate constant compromises with the SPD-Green majority in the Bundesrat, the upper house where the 16 federal states are represented. Last, most of the upcoming Eurozone crisis decisions have to be taken by a majority of the plenary of the Bundestag (e.g. Spain’s ESM request). For reasons of political legitimacy, both the current and any new government would probably opt for broad approval of measures to be taken, even if formally not required.

Hence, the next Federal government will probably not be very different from the present one as far as EU economic policy is concerned. Germany is likely to stick to its course of providing as much financial and political support as is required to contain an escalation of the crisis in exchange for continued commitments to reform, adjustment and institutional improvements in the crisis countries. At the same time, it will seek to carefully limit the upside risks to its financial commitments, which are already very large in both absolute and relative terms. Moreover, the current paralysis of decisions on controversial issues in Europe might not be resolved after September 22. It is plausible that decisions which eventually need a treaty change might even be postponed to a later moment given European elections and French municipal elections in 2014, and British elections in 2015.

The fact that the elections will probably not change Germany’s political course in Europe is reflected in the run-up to the election itself. It seems that, with little to separate the Christian Democrats from the main opposition, the subject has been delicately avoided. This is also because the SPD cannot win votes by bashing Mrs. Merkel on her Eurozone policy as her balancing act of being pro-European, while defending the national interest, is what the voters want. The election campaign has therefore been dominated by domestic concerns, rather than by the Eurozone crisis given that Germans have been unscathed by the soaring unemployment and sweeping public sector cuts of Spain or Greece.

With this stated, the Eurozone crisis broke cover when finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble conceded in a speech to party supporters that Greece would need a third bailout, though he ruled out the need for another debt haircut. According to the Financial Times, a 3-4 billion euro financing gap became evident in Greece’s second bailout this year, but officials had sought to play down the shortfall. That still ignores a warning by the IMF which said in July that the financing gap, which it puts at 11 billion euros to cover the period into 2015, would need to involve some debt relief. Eurozone officials have insisted they will not discuss further debt relief for Greece until April 2014 at the earliest.

Bailing Greece out again is very unpopular among Germans, as shown in the BILD newspaper which is running a campaign to get all the political parties to commit themselves to “no more money for the Greeks”. SPD candidate Steinbrück took the occasion to turn the spotlight on the government’s silence on the subject and urged the government to come clean with voters about the costs of another Greek rescue. Nevertheless, in an interview to the Wirtschaftwoche on August 26, Schäuble insisted that there were no “secret plans” regarding Greece that had been postponed to the period after the elections.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/15yg8rN

_________________________________

Philine Schuseil

Philine Schuseil

Philine Schuseil is currently enrolled in the Master of Science in Economics at the Toulouse School of Economics in France, and she holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics from the Humboldt-University of Berlin. During her studies, she spent one year at the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Cachan in France. Her work experience includes internships at the OECD, the French Ministry of Economy and at Bruegel.