In recent years, the EU has made efforts to promote stability and shared values with the countries to its east through the Eastern Partnership. However, as David Rinnert writes, the process of ‘light integration’ of these ex-Soviet states has been plagued by political failings and the influence of Russia. He calls for a rethink of Europe’s eastern strategy to ensure that it offers genuine long-term prospects for the EU’s neighbours and fully takes into account the economic and political dynamics of the region.

In recent years, the EU has made efforts to promote stability and shared values with the countries to its east through the Eastern Partnership. However, as David Rinnert writes, the process of ‘light integration’ of these ex-Soviet states has been plagued by political failings and the influence of Russia. He calls for a rethink of Europe’s eastern strategy to ensure that it offers genuine long-term prospects for the EU’s neighbours and fully takes into account the economic and political dynamics of the region.

On 28-29 November, representatives from all 28 EU member states, the European Commission and the Eastern Partnership (EaP) states gathered in Vilnius, Lithuania for the third high-level EaP summit to discuss the future of the initiative and EU relations with its eastern neighbourhood. Initially seen and billed as ‘one of the most important moments this year not only for the EU, but also for the EaP partner states’, the summit and a number of events ahead of it have turned out to be exceptionally disappointing from the EU’s perspective.

The EaP: Initial objectives and the first years of implementation

The EaP was initiated by Poland and Sweden and was adopted as an eastern dimension of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) in 2009. It comprises six post-Soviet states, namely Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. The initiative was designed to supplement the ENP and enable political and economic integration without the promise of enlargement.

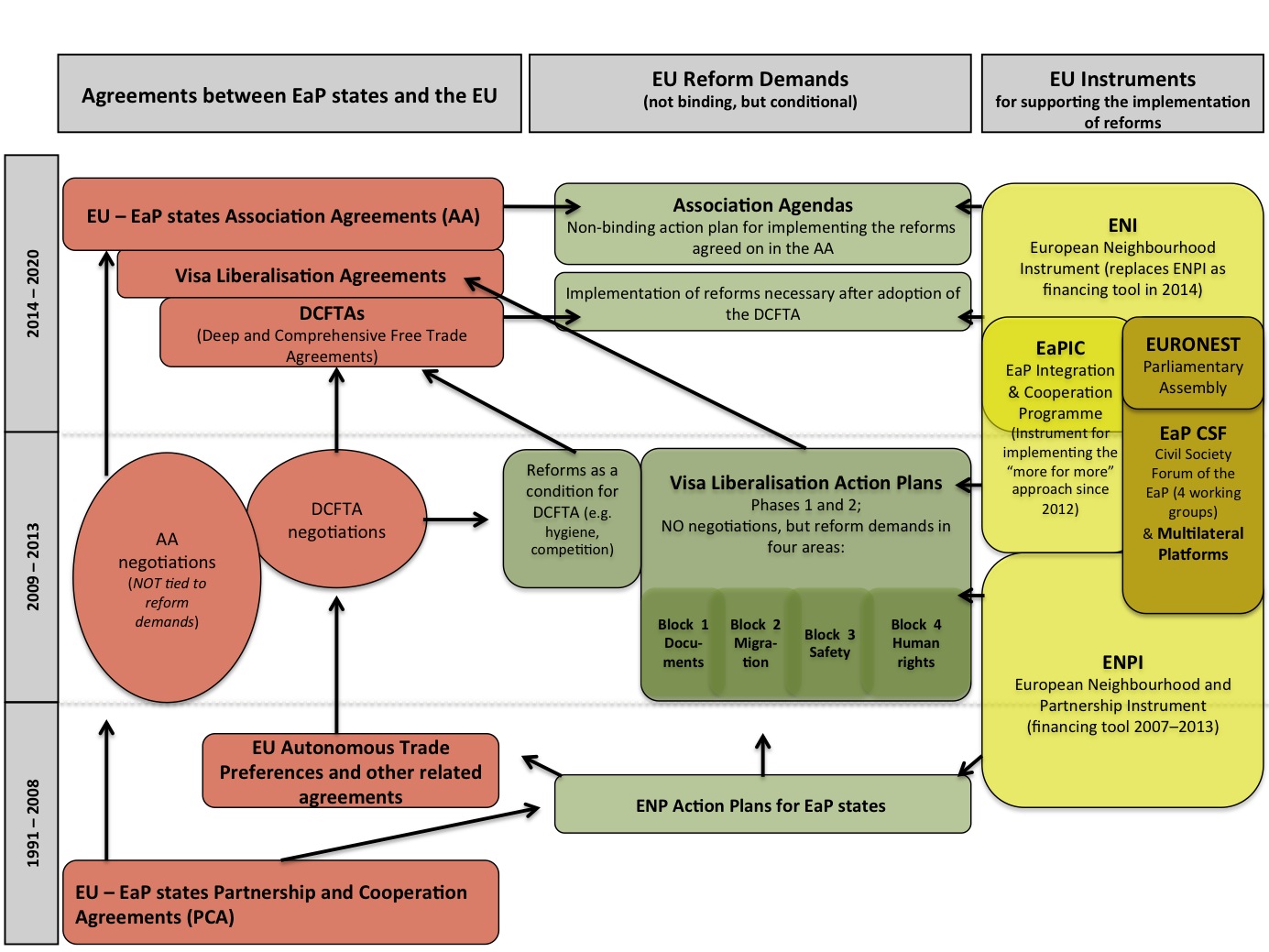

The EU’s core offerings within the context of the EaP are Association Agreements (AA), Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTA), and visa liberalisation agreements. The EU has provided instruments for all three areas, ranging from financial aid to technical assistance and multilateral platforms, focusing mainly on legal approximation of partner countries (see Figure 1). The guiding principles of the collaboration are joint ownership and conditionality, which means that both parties should set priorities together. At the same time, the scope of the assistance depends on each partner country’s performance in reforms. As a result, the EaP is in reality a relatively technical policy initiative, in stark contrast to the geopolitical dynamics of the region.

Figure 1: Mechanisms of collaboration between the EU and EaP partner states since 1991

While it began with high hopes in Brussels, the EaP’s implementation over the past four years has been mostly disappointing. While Azerbaijan and Belarus showed little interest from the beginning, the EaP has also not yielded great results beyond legal approximation in the other four countries. There are different reasons for this.

While it began with high hopes in Brussels, the EaP’s implementation over the past four years has been mostly disappointing. While Azerbaijan and Belarus showed little interest from the beginning, the EaP has also not yielded great results beyond legal approximation in the other four countries. There are different reasons for this.

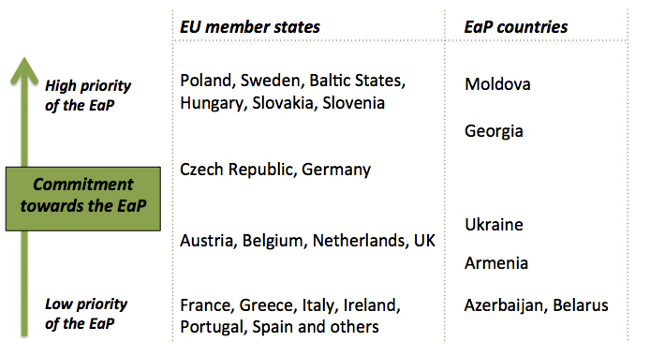

On the EU’s side, they include a lack of interest from the majority of member states (see Figure 2), a renewed focus on the southern neighbourhood due to the Arab spring, and the financial and economic crisis of the past few years. On the eastern neighbourhood’s side, even the most pro-European partner states have lost their initial enthusiasm for the EaP, due to disproportionate conditionality (e.g. a large number of conditions have been imposed simply to begin DCFTA-negotiations with Georgia and Moldova), limited attractiveness of the incentives offered (especially in the short-term) and the lack of a clear long-term strategy.

Figure 2: Commitment towards the EaP: An overview

Nevertheless, up until late 2012, the EU remained optimistic, as negotiations for Association Agreements were underway with four of the six EaP partner countries and officials in Brussels hoped that the Vilnius summit in 2013 would finally mark a breakthrough for the EU’s policy in its eastern neighbourhood.

Nevertheless, up until late 2012, the EU remained optimistic, as negotiations for Association Agreements were underway with four of the six EaP partner countries and officials in Brussels hoped that the Vilnius summit in 2013 would finally mark a breakthrough for the EU’s policy in its eastern neighbourhood.

The political economy of the EaP in 2013: Reasons for a disappointing Vilnius summit

This year started off with a large-scale political scandal in Moldova, leading to the ousting of former Prime Minister Vlad Filat, which called into question the EU’s narrative of the small republic as the “success story” of the EaP. Despite the finalisation of negotiations in 2012, the signature of an Association Agreement with Ukraine was also put on ice due to on-going EU concerns about selective justice in the country, referring mainly to the jailing of former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko.

At the same time, Russia began to intensify its activities in the region, aiming both at preventing the planned signatures of EU-EaP agreements in Vilnius and encouraging the EaP partner states’ participation in its own Eurasian Customs Union (a Russian initiative for economic integration, intended to be expanded to a political union in the coming years). Ahead of the Vilnius summit, Russia’s engagement was fruitful. In September 2013, Armenia declared it no longer wanted to sign the negotiated Association Agreement with the EU, but would instead join the Eurasian Customs Union.

To the EU’s surprise, Ukraine followed Armenia’s example in mid-November, shortly before the Vilnius summit, with Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych publicly declaring his country’s support for the Russian integration project. As Ukraine is by far the largest and most important country in the EaP, many saw the signature of agreements with Kiev as the litmus test of the initiative’s success.

Considering the EaP mainly functions as a technical initiative, the EU did not sufficiently take into account the “Russia factor” and the geopolitical implications. At the same time, Brussels overestimated its own importance to EaP countries. For instance, despite the fact that the EU accounts for approximately one third of Armenia’s and Ukraine’s trade, taken together, Russia and the other CIS states are equally important for both countries in terms of trade volumes.

Beyond offering further short-term benefits, such as reduced gas prices for EaP states, Russia’s leadership also increasingly made use of (credible) threats throughout 2013. For instance, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin said that “Russia would close its borders to goods from any country signing the EU association agreements and migrant workers would be banned from finding jobs in Russia”. Taking into account these Russian “carrots” and “sticks”, as well as the relatively high short-term costs of implementing AA, DCFTA and visa-liberalisation agreements with the EU, it is understandable why Armenia’s and Ukraine’s political elites decided to opt for the Eurasian Union.

The above-mentioned events earlier this year led to a summit that could not yield the results the EU had initially hoped for. Among the few pieces of good news from Vilnius are the offer of a visa-free regime for Moldova and the initialling of Association Agreements and Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements with Georgia and Moldova. While these results mark significant steps for both countries in their relations with Brussels, they do not make up for the dashed hopes of the EU for Armenia and especially Ukraine. The joint declaration from the summit was also significantly watered down in the final version, in just another sign of the need for an EaP revision after Vilnius.

The way forward for the EU: Between geopolitics and more effective policies

As outlined recently in a number of policy papers, a revision of the EaP needs to take into account the realities mentioned above. First, when adjusting the EaP, the EU should factor in the economic (and, in some cases, political) dependence of most partner countries on Russia. Second, this also implies a re-design by the EU of short- and long-term incentives for partner countries. While agreements such as DCFTAs would benefit most EaP countries in the long-term, costs would arise for local economies in the beginning (e.g. for Moldovan farmers through increased competition with EU farmers).

Additionally, the EU has to offer a strategic perspective for EaP states: what is on the table for them after the AA’s implementation? Third, for different reasons the EU has so far largely excluded security issues from the EaP. Four out of the six EaP states are involved in internal long-running conflicts – Armenia and Azerbaijan [Nagorny-Karabakh], Georgia [Abkhazia and South Ossetia] and Moldova [Transnistria]. However, Russia continues to use these conflicts to influence the region and the EU has to think about ways of incorporating conflict resolution instruments into the EaP.

Following Vilnius, the EU needs to rethink the EaP. The approach of ‘enlargement light’ has largely failed, not only in the east but also in the south, where the EU’s other neighbourhood initiative (Union for the Mediterranean) has been even less successful in light of the Arab Spring. This will not be an easy task, though, especially since interest in the eastern neighbourhood varies widely among EU member states. Without a reform of the EaP, the EU will not be able to achieve the initial objectives of its neighbourhood policies: creating a neighbourhood of stable and democratic states which share the EU’s fundamental values.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/IoA0dj

_________________________________

David Rinnert

David Rinnert

David Rinnert is a Master of Public Administration dual degree candidate at the LSE and Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, with a focus on development and governance in the post-Soviet space. Following his undergraduate studies in Berlin, New York and Paris, he worked in Georgia and Moldova. In addition, he is an independent policy analyst and has published several papers on the region. You can follow him on Twitter: @DRinnert

1 Comments