Turnout at European Parliament elections has fallen significantly since the first elections in 1979. This has led some politicians and commentators to suggest that integrating national parliaments into the EU’s legislative process may be a more effective method for improving the EU’s legitimacy. Jon Worth argues that the logic underpinning such arguments is undermined by the fact that national elections have also witnessed a substantial drop in turnout over the same period. Moreover, in most EU countries citizens actually trust their own parliament less than the European Parliament, raising doubts over the ability of national parliaments to confer a greater degree of legitimacy.

Turnout at European Parliament elections has fallen significantly since the first elections in 1979. This has led some politicians and commentators to suggest that integrating national parliaments into the EU’s legislative process may be a more effective method for improving the EU’s legitimacy. Jon Worth argues that the logic underpinning such arguments is undermined by the fact that national elections have also witnessed a substantial drop in turnout over the same period. Moreover, in most EU countries citizens actually trust their own parliament less than the European Parliament, raising doubts over the ability of national parliaments to confer a greater degree of legitimacy.

With the European Union struggling to overcome the financial crisis, and the knock-on impact on the politics of the European project, national political classes have been grasping for solutions to the EU’s perceived legitimacy problem. One of the most commonly cited solutions is to seek a greater role for national parliaments in EU decision making.

The case in favour is that while the European Parliament has enjoyed increasing powers since its first direct elections in 1979, election turnout has consistently declined. This seeming contradiction, proponents of a greater role for national parliaments contend, shows that the European Parliament is not the way to ensure the EU’s legitimacy. National parliaments – as opposed to national governments – are by definition democratic, and thanks to higher turnouts are more legitimate than the European Parliament, and hence the EU can become more legitimate through greater involvement of national parliaments.

Arguments of this nature have been proposed on this very blog by Mats Persson, and elsewhere by David Lidington and Charles Grant, and similar sentiments even appear in the German national coalition agreement. The problem is that none of the aspects of the argument in favour of a greater role for national parliaments hold up to much scrutiny.

While it cannot be contested that the legislative powers of the European Parliament have increased with every change to the EU’s Treaties since 1979, principally through the increasing number of policy areas where the Ordinary legislative procedure (formerly Co-decision) applies, it nevertheless remains the case that the European Parliament has only very limited scope to change the overall direction of EU integration. A voter can still have no expectation that a more social democratic or more conservative EU, or more or less integrated EU, will emerge as a result of the outcome of a European Parliament election.

The problem, then, is that while the European Parliament’s legislative powers have increased, it still fails to meet Schumpeter’s classic definition of a party system: that parties present programmes; voters make an informed choice between competing parties; the successful party puts its programme into practice; and the governing party is judged on its performance at the next election.

So while the European Parliament may wield legislative clout over everything from fishing quotas to food additives to CO2 emissions from cars, the connection between the outcome of the European elections and parties being judged five years later is still missing. The Parliament’s additional power is incomprehensible at best and invisible at worst for the voters. The argument that more legislative powers should equate to higher turnout is spurious.

That turnout has been falling in European Parliament elections is also not as clearcut as the headline figures suggest, and ignores the context in which this has been happening. Firstly, the number of countries with compulsory voting skews the European election turnout figures (2 of 9 Member States in 1979, 3 of 10 Member States in 1984, 3 of 27 Member States in 2009). Fewer countries with compulsory voting means a lower average turnout. Secondly, enlargement of the European Union has brought countries into the European Union with traditionally lower turnouts in national elections than in the ‘old’ member states.

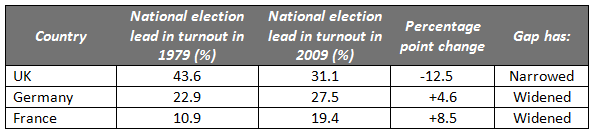

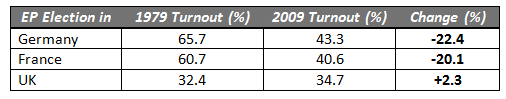

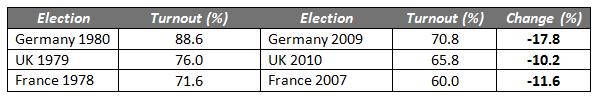

Table 1 below compares election turnout in the three largest Member States – the United Kingdom, France and Germany – between the 1979 and 2009 European elections, and between the Parliamentary elections that took place the least amount of time before or after the EP elections in each country. In section a) the differences in turnout between the 1979 and 2009 EP elections are shown, while section b) shows the differences in turnout between the closest general elections to the 1979 EP vote and the closest general elections to the 2009 EP vote. Section c) illustrates the differences in the gap between general election and European election turnout between 1979 and 2009.

Table 1: Changes in turnout at the European Parliament elections in France, Germany and the UK from around 1979 to around 2009

(a) Turnout at European Parliament elections

(b) Turnout at nearest Parliamentary general elections

(c) The gap between general election and EP turnouts

Note: In (a) The UK European Parliament election in 1979 was held using the first past the post electoral system. In (b) The elections contained in the table are the closest national elections to the 1979 European Parliament elections and the 2009 European Parliament elections. Source: European Parliament; International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

While the declines in France and Germany at European elections are more marked than national declines, the UK shows the opposite trend – with national turnout down and European election turnout up. At the very least turnout in European elections should be seen against the backdrop of declining participation nationally as well as at the EU level, with the second order elections effect explaining the initial difference in turnout. To put it another way, it is not as if all is healthy at the national level but problematic at the EU level; there are problems at both levels.

The EU’s Eurobarometer poll asks European citizens about their trust in political institutions, and here too a comparison between the European Parliament and national parliaments can be made. Across the EU-28, 39 per cent of citizens trust the European Parliament, versus 25 per cent that trust their national parliament. In only 5 Member States – the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria, Sweden and Finland – is the trust in the national parliament higher than trust in the European Parliament.

Lastly the behaviour of national parliaments when it comes to EU business so far gives no additional argument why their role should be further strengthened. With the notable exception of the Danish and Finnish Parliaments, which have each developed nuanced and strong ways to control national Ministers going to Council meetings, national scrutiny of EU business remains sporadic, poorly resourced, and often reduced to complaining after decisions have been taken in Brussels. That the “yellow card” procedure for national parliaments has been used just twice since its introduction is testimony to this.

That national parliaments behave this way is logical from a self-interested point of view: ambitious, hard-working politicians would prefer to deliver changes to schools, hospitals, roads or railways nationally than embroil themselves in the technical matters of EU law. A political party is – rightly – never going to win or lose an election nationally on the basis of its ability to scrutinise EU law.

All things considered, the notion that the European Parliament’s greater legislative power should equate to higher election turnout is a spurious argument, and turnout should in any case be seen in the context of declining turnout at national level too. Further, when it comes to trust and the behaviour of national parliamentarians on EU business to date, there is no case for a greater role for national parliaments in EU decision making.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1bhGSqo

_________________________________

Jon Worth

Jon Worth

Jon Worth is a Berlin-based blogger and campaigner. His blog – www.jonworth.eu – is one of the longest running blogs dedicated to EU affairs. He works as a freelance communications consultant and is a visiting lecturer at the Graduate Institute of International Affairs, Geneva, and the University of Maastricht, Netherlands.

Jon, thanks for your reflection. Two points I think you should consider. First, the “trust” as measured by Eurobarometer is largely pointless. Do you trust the UN? Probably more than your “corrupt” national politicians, because you don’t know what it does (I know you do, but most of the respondents to EB don’t…) and hence don’t really care. I would argue that the same is for the EP, too little knowledge about its powers, its work and the work of individual MEPs can drive “trust” higher. You should check the national figures for EP trust after some national scandals – for example cash-for-amendments. Trust was not as high then. Second, I would always argue that voters are always better informed on national politics – they read more about it, know more and care more. Tell me, how many “European” newspapers your parents read? Do they know at all what the EP is doing at the plenary at the end of February? This relates to the previous point, but also drives another arguments in favor of greater scrutiny powers for national parliaments. At least, you know those people and you read about them. In theory you have a functioning national media scene, which is hardly the case for EU affairs. And finally, what is your suggestion? To keep things as they are? To have pan-European lists? Lead candidates for European Commission president? Sure, that helps, but I would tend to be a bit more realistic and claim that democracy to a great extent still resides with the nation – something we should hope to change, but not ignore.

One of the biggest obstacles in the credibility of the EP is simply that it lacks compared to national parliaments in the North in both credibility and legitimacy.

It needs Northern style credibility to have that credibility (among others that is).

Therefor how the whole of the EU with semi-platana republics overrepresented looks at things is a horrible criterion. The South want Northern standards that is why they like the EU more than their local reps.

It should therefor step up to Northern level and no better way to do that is give all (Northern alone is a no go of course) parliaments the supervision. So part of the supervision is Northern and with basically a veto like situation (it will depend on how votes are counted or when vetos are possible) say the Finns or the Danes can push the thing forward. I simply see no other way. Dodgy MPs out of Europe’s own 3rd world as far as corruption goes at least will always be a problem.

Another big issue is that the EP simply has a nearly complete lack of credibility. Turn out is an indication but also that it is seen nearly everywhere as a second class election.

An important third point it is not in the first place about increasing credibility. In the first place it should go over having a democratic platform.

This is simply lacking. In other words until the EP gets democratical legitimacy and real one where the people also have the choice to abolish it for instance this is an issue without any priority. First the preliminary questions should be answered.

Jon, I thank you for a balanced perspective on legitimacy of the European Parliament vis-à-vis national parliaments. On one hand it is very tempting to give the national parliaments influence on the EU process of decision making. It would make national politicians responsible for EU decisions as well. This might improve the “perceived” legitimacy of EU decisions among the Europeans. This holds true for the strong role of the Council of the European Union as well in which the member states’ executive branch of government have a strong impact on the legislative process in EU. This method is probably based on the German definition of federalism, which is more “cooperative”, where states and the federal government are sharing responsibilities. This is different from the American “dual federalism”, where competences are clearly split between the state and the federal level of government and the states are only represented directly in the Senate.

But this is the problem in the EU. It makes EU less visible in the daily lives of the 500+ million people. In addition it is blurring the responsibilities of the national politicians and is diminishing the role of the European Parliament. Furthermore this makes it much more fun for journalists to be around national capitals instead of Brussels.

I can see some advantages of this cooperative model. However, I tend to prefer a more dual model in which national politicians are dealing with national issues and EU politicians in the executive and legislative branches of government should be elected directly by the people of Europe.