EU citizens have the right to live and work in any other EU state. As Roxana Barbulescu writes, however, this principle of freedom of movement has come under pressure from a number of recent developments. Focusing on the UK, she notes that while there are substantial economic benefits from freedom of movement, there is now growing support for putting restrictions in place. In the short term this will include putting a minimum earnings threshold on EU citizens’ access to certain types of welfare from 1 March, but across Europe far wider changes could take place if politicians attempt to placate anti-immigration sentiments among their electorates.

EU citizens have the right to live and work in any other EU state. As Roxana Barbulescu writes, however, this principle of freedom of movement has come under pressure from a number of recent developments. Focusing on the UK, she notes that while there are substantial economic benefits from freedom of movement, there is now growing support for putting restrictions in place. In the short term this will include putting a minimum earnings threshold on EU citizens’ access to certain types of welfare from 1 March, but across Europe far wider changes could take place if politicians attempt to placate anti-immigration sentiments among their electorates.

The liberal, cosmopolitan and gay marriage-friendly United Kingdom is currently facing a difficult challenge. On 1 January 2014, temporary restrictions placed on workers from Romania and Bulgaria ended – an event which generated a wave of hysteria in British politics. Tabloids such as The Daily Mail and The Sun featured stories of remote impoverished villages in Romania and printed glossy pictures of Roma Romanians begging and living in bad conditions in Marble Arch, one of the most emblematic, tourist-friendly and affluent areas of London. This media coverage was ostensibly designed to highlight the degree of poverty of people in a far-away country.

However, the challenge goes well beyond the press and it has triggered strong declarations from politicians and party leaders. Prime Minister David Cameron and cabinet ministers have promised that the current coalition government will look at ways to limit immigration from the EU and have announced a set of measure that would restrict access to social benefits. Cameron has insisted that, if his Conservative Party wins the next election in 2015, freedom of movement would be renegotiated as part of a reform of the UK’s relationship with the EU. He has also promised a referendum on the renegotiation as to whether the UK should remain within the EU.

So what is going on here? Why does the UK seem to fear immigration from Romania and why is it challenging EU freedom of movement? The simple answer is because of UKIP. The more accurate answer is far more complex than that.

UKIP and EU freedom of movement

The UK Independence Party (UKIP) has changed the dynamics of electoral competition in the UK, pushing mainstream parties into adopting a more conservative stance on immigration. The party’s success at the English local elections in May 2013 was unprecedented and alarming for the major Westminster parties, particularly so for the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. UKIP came out of the elections with 147 local councillors, adding 139 seats from the mere 8 it had won in 2009. With 23 per cent of all votes cast going to UKIP, they emerged as the third most popular party after Labour (which received 38 per cent of the vote) and the Conservatives (which received 31 per cent of the vote). The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats lost 335 and 124 seats in local councils respectively.

UKIP currently has no representation in the UK Parliament, but it got as close as it has ever come to winning a parliamentary seat in the South Shields by-election in May 2013, where the seat was left vacant by the departure of former Labour Foreign Secretary David Miliband. South Shields is a constituency where Labour has won uninterrupted since 1935. The by-election put UKIP second (23 per cent of the vote) only after Labour, which won the seat (with 50 per cent of the vote), but far ahead of the Conservatives (11 per cent of the vote).

The clear defeat of the Conservatives and UKIP’s success in a historically safe Labour constituency have meant that both parties have had to pay more attention to UKIP and to UKIP’s voters. They are mostly older (71 per cent of UKIP voters are over 50 years old), poorer than Conservative or Labour voters (23 per cent of UKIP voters live in households whose total income is more than £40,000, compared with 38 per cent of Conservative and 28 per cent of Labour voters). It has also meant that the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats have to take on board the issues raised by UKIP – and Romanian and Bulgarian migration made it to the top of UKIP’s concerns.

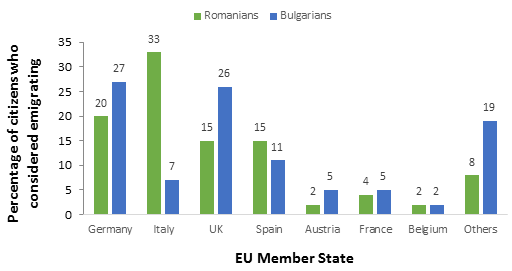

But why does the UK seem to fear immigration from Romania? And should it fear it? For many people in the UK, Romanian immigration seems very similar to Polish immigration. After Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004, the UK opened its labour market to Polish workers immediately, without the types of transitional controls placed on Romanians and Bulgarians in 2007. Many people came from Poland, and today more than 700,000 Poles live and work in the UK. With the expiration of the temporary restrictions on workers from Romania and Bulgaria, some have feared that a similar situation might happen again, with high numbers coming to the UK. Furthermore, Britons seem to fear Romanian migration more than other Europeans because in general they fear immigration more. Anti-immigrant sentiments are on the rise across Europe, but the British clearly tend to regard immigration more negatively than other Europeans, as shown in Chart 1 below.

Chart 1: Percentage of citizens in UK, EU, Western Europe, and Scandinavia who rank immigration as one of the two most important issues facing their country

Source: Ipsos MORI

Source: Ipsos MORI

Currently, around 80,000 Romanians work in the UK, and it is unlikely that the numbers will increase significantly in the short term. In the 2004 enlargement, out of the 15 old EU Member States, only three countries – UK, Ireland and Sweden – fully opened their labour markets immediately to workers from Poland and the other new Member States following their accession. This meant that immigrants naturally preferred to go to these destinations.

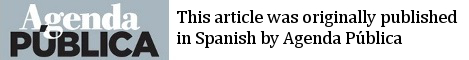

This time, restrictions for Romanian and Bulgarian workers ended in 2014 in nine EU Member States. The remaining 16 countries had already given them full labour market access before this date. Furthermore, if Romanians and Bulgarians decide to emigrate, they are more likely to go to Italy and Germany than to the UK, as they feel culturally and linguistically closer to those countries, and they already have large expatriate communities. An opinion poll commission by the BBC in April last year found that, of those who considered looking for work abroad, only 15 per cent of Romanians and 26 per cent of the Bulgarians listed the UK as their top choice (see Chart 2 below).

Chart 2: Preferred destination for Romanians and Bulgarians who considered emigration in last 5 years

Source: BBC – Romania / Bulgaria

Source: BBC – Romania / Bulgaria

Since Romania and Bulgaria are the poorest countries in the EU, some have feared that large numbers of people would come to the UK simply to claim welfare benefits. UKIP, the Conservatives and most recently Labour have announced their desire to limit access to social benefits for all non-UK EU citizens. From 1 March, a minimum earnings threshold will be put in place that EU immigrants must meet before claiming certain benefits.

A recent study by University College London shows that EU migrants are more likely to contribute to the UK’s economy and less likely to receive social benefits than UK citizens. It found that, between 2001 and 2011, immigrants from the European Economic Area (the EU plus Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein) contributed 34 per cent more to the economy than they took out, with a net contribution of around £22.1 billion. At the moment, the UK is benefiting from Romanian migration by being able to recruit fully trained and experienced doctors to fill current shortages in the NHS, at the expense of creating a shortage of doctors in Romania.

Despite calls for a sensible migration debate, with accurate facts and numbers, the political debate continues to be one-sided. For example, in January it emerged that the British government tried to supress a report that confirmed the positive contribution of European migrants to British society. It is true that a voice must be given to the significant disenfranchised segment of a population which has been ignored and which has over time developed strong anti-immigrant feelings. People in this segment may think that any immigration, regardless of its economic benefit or intensity, is bad for the UK.

This is a group often forgotten by politicians in ambitious development plans, and one that is remembered only when it comes to cutting welfare. It is impoverished and ill-equipped to compete in the UK – one of the world’s most competitive and deregulated labour markets. If only the political class could have invested more in them earlier on, it would have prevented the widening social gap. On immigration they have won – they are voices the parties in Westminster seem to be listening to. Yet they have themselves forgotten that it is social factors and the labour market, not immigration, which affects them and their families.

Meanwhile, freedom of movement is being questioned more than at any other point in its history. The return of immigration quotas was recently backed in a referendum in Switzerland and will have an impact on the Swiss-EU agreements pertaining to freedom of movement. Germany, Austria and the Netherlands have also joined the UK in pushing to limit freedom of movement. On 15 January, the European Parliament hosted a debate on the issue. The result of such a re-evaluation of free movement rights is likely to be negative and trigger reactionary limitations that will adversely affect all EU citizens, including the French, Italians and Spaniards living in London today.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1jI6XOG

_________________________________

Roxana Barbulescu – University of Sheffield

Roxana Barbulescu – University of Sheffield

Roxana Barbulescu is Research Fellow in the Department for Sociological Studies at the University of Sheffield and Country Expert for Romania in the EUDO Citizenship Observatory at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute. Her research interests focus on state-driven migration in its voluntary and mandatory policy-variants, immigrants’ rights, intra-European mobility and migration governance, access to citizenship, EU citizenship, anti-Roma prejudice, anti-discrimination policies and unaccompanied minors in asylum systems. Follow her on Twitter: @roxanabarbulesc

You might humour me & tell me why you use this phrase? “The liberal, cosmopolitan and gay marriage-friendly United Kingdom” What point are you trying to get across?

I’d guess the point is that the UK is liberal in many ways yet also more anti-immigration than many other countries in Europe.

Except that is not the case. The UK is the most pro immigration but I agree it is anti spongers & allowing economic refugees from the EU to take the low scale jobs that students used to do to help them through third level education. As JFK said ask what you can do rather than what you can get & if its the former you will be made welcome

All you’re really doing there is rationalising anti-immigration sentiment – i.e. you’re trying to argue that we aren’t really “anti-immigration” per se, it’s simply a rational reaction to supposed “economic refugees” (about as loaded a term as I can think of) coming to the UK.

Show me an anti-immigration movement in any country in the world which doesn’t make a claim to be “rational”. It’s always justified on the basis of supposed practical concerns, but you’re sticking your head in the sand if you think the entirety of anti-immigration sentiment in the UK is based on simple economics – particularly when we already know immigrants from the rest of the EU provide a clear benefit to the UK’s economy.

Well I have no issue with Immigrants who chose to retire sell their assets back home & bring them over to the UK & live of their home state pensions which is what the majority of UK expats are doing to swell the numbers of so called UK migrants. We cannot sustain the numbers that are coming in without jobs that can maintain their families. When UK families move to spain they have to pay for their kids to learn Spanish, they have to pay to send their kids to English language schools to get them past the language obstacle. In the UK the state picks up the bill. I have private insurance as does everyone I know in Malaga for their medical costs why can’t immigrants coming to the UK do likewise? at least for say the first 5 years? It would make their presence much easier to take for the services. No immigrants should have access to public housing for the same period of time if not longer. We refused to take in Hong Kong citizens when we handed their country over to the Chinese & many of those seeking refuge we’re well able to provide for themselves for the simple reason our public services couldn’t cope with the potential numbers & they held UK passports

These arguments are made regularly, but where is the evidence to back it up? We know from the recent study on this subject that EU immigrants contribute more to UK finances than is spent on them through public services. Therefore they don’t damage public services, they actively contribute to them. Public services would be worse if we had no EU immigration, not better.

We have a significant deficit in the UK so putting restrictions on something that actively helps our economy is the last thing we should be doing.

We have to pay too for our children to learn English because the English state school are of such a poor quality! My daughter is learning English because I enrolled her to an independent school otherwise she would not have learned one word in the State school she was registered!

“Currently, around 80,000 Romanians work in the UK, and it is unlikely that the numbers will increase significantly in the short term” (2014)

Given that the current number of Romanians is now over 500,000 (and that’s only an official number) you might like to reflect that concerns expressed in 2014 were entirely justified.