Hungary held parliamentary elections on Sunday. As Erin Marie Saltman writes, Viktor Orbán’s ruling Fidesz party came out comfortably ahead in the vote and will maintain its majority in the next parliament. However with the votes still being counted, there is still some doubt over whether Fidesz will have the ‘supermajority’ required to alter the country’s constitution. Regardless of the final count, she argues that the elections mean Hungary will continue along a more centralised and nationalistic path, including a potential reorientation away from ‘Western powers’ and toward Russia.

Hungary held parliamentary elections on Sunday. As Erin Marie Saltman writes, Viktor Orbán’s ruling Fidesz party came out comfortably ahead in the vote and will maintain its majority in the next parliament. However with the votes still being counted, there is still some doubt over whether Fidesz will have the ‘supermajority’ required to alter the country’s constitution. Regardless of the final count, she argues that the elections mean Hungary will continue along a more centralised and nationalistic path, including a potential reorientation away from ‘Western powers’ and toward Russia.

The primary outcome of Sunday’s national elections in Hungary did not hold many surprises as right wing conservative party, Fidesz, took a clear lead over their opposition, winning in all individual constituencies apart from Budapest and Szeged. Polls taking place in the months leading up to the national elections had predicted a clear Fidesz win and the party has won 96 out of the 106 constituencies counted so far. However, there were significant gains made by the radical right party Jobbik and disappointing results for the liberal-left coalition, which had united six political parties in an attempt to turn the tide against Fidesz.

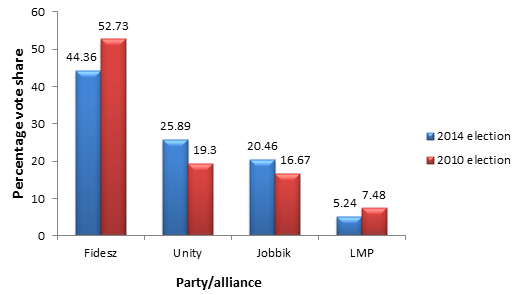

With 96 per cent of the vote counted by nearly one in the morning last night, results showed Fidesz support at around 44.5 per cent. The Unity Alliance, made up of both old and new liberal and left wing opposition parties, currently stands at just under 26 per cent. Meanwhile, Jobbik has strengthened their support, increasing from 16.67 per cent in the last elections, to 20.54 per cent. Green party LMP has also just barely passed the 5 per cent electoral threshold with 5.25 per cent. Chart 1 shows the provisional vote shares for the four main alliances.

Chart 1: Provisional vote shares in 2014 Hungarian election and comparison with 2010 results

Note: Unity is an alliance of five parties. These five parties did not compete as an alliance in 2010, but they have been grouped in the chart for context – the figure for 2010 represents the vote share for the largest party in the alliance, the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP). Source: Hungarian national voting site

The National Election Office reported a 60.48 per cent turnout. Although this is slightly less than the 64.38 per cent turnout in 2010, Hungary remains around the EU average of 68 per cent for national election turnout and maintains a higher turnout than most other Central and Eastern European countries.

Splitting hairs for the supermajority

However, the vote counting has become tense, as the two-thirds majority previously held by Fidesz is currently dependent on one district seat in Budapest and very close results in Miskolc. The exact electoral outcome is now expected to take another day or two to ensure every vote is counted in this tense finale. Whether or not Fidesz will manage their previous supermajority depends primarily on the voting results of Budapest’s 15th District, where Ágnes Kunhalmis (Unity Alliance representative from the Socialist Party – MSZP) faces Simon Kucsák (Fidesz).

If Kucsák wins, Fidesz will maintain their supermajority in parliament with 133 of the 199 parliamentary seats. If Kunhalmis wins, Fidesz will be one parliamentary seat short of their previous decision-making powers. The voting counts coming in last night after midnight gave 37.61 per cent to Kucsák and 37.57 per cent to Kunhalmis. Chart 2 below shows the provisional seat distribution.

Chart 2: Provisional distribution of seats in Hungarian parliament

Note: Not all votes have been counted: it is possible Fidesz-KDNP could end up with 132 seats after final count. In terms of parliamentary alliances, Fidesz and the Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP) form an alliance, while the Unity alliance is made up of the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), Together 2014, the Democratic Coalition (DK), Dialogue for Hungary (PM), and the Hungarian Liberal Party (MLP).

Close election calls in Miskolc, a stronghold of Jobbik, could also swing the balance as votes seem evenly split between Zoltán Pakusza of Jobbik (31.56 per cent), László Sebestyén of Fidesz (31.11 per cent) and László Varga of the left-wing coalition (30.21 per cent).

The people’s choice: Fidesz and Jobbik

This election, in many respects, represents the solidification of Fidesz’s ‘new path’ for Hungary. The election itself put into practice new legislation put forward by the Fidesz government, redrawing voting districts and decreasing the number of seats in parliament from 386 down to 199. This was also the first time that Hungarian national elections were decided in one, rather than two, rounds of elections.

Despite a number of complaints and critiques from the opposition over what was perceived as electoral gerrymandering, and concerns expressed over potential electoral fraud, the elections took place without a hitch. Despite all opposition efforts, Fidesz succeeded in maintaining its hegemonic presence and Jobbik maintained a strong nationalist stance on issues, gaining legitimacy as a stable and viable party for many Hungarians.

In the meantime, liberal and left wing opposition forces failed to appeal to the average voter. In the year leading up to elections the Unity Alliance had slowly united the Socialist Party (MSZP), the Democratic Coalition (DK), the Hungarian Liberal Party (Liberálisok) and the Together 2014 movement-party along with the LMP splinter party Dialogue for Hungary (PM). Yet despite this catch-all opposition union, internal disputes between party leaders were made a public affair where egos seemed to come before ethos.

The opposition also seemed to campaign almost solely on attacking the Fidesz government’s actions in the last four years rather than presenting comprehensive viable reforms. Even in the aftermath of defeat, opposition leaders seemed keener on continuing their attack rather than conceding. Former Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány, leading the Democratic Coalition Party as part of the Unity alliance, was quoted as saying: “We believe in a country where the people are free, not the powerful… Viktor Orbán’s Hungary is not my country.”

The next four years

If Fidesz continues on its current course over the next four years, more changes can be expected to both domestic political infrastructures and international relations. Internally, the continuation of centralising efforts can be expected, affecting utilities, educational institutions and judicial systems. Externally, Fidesz is currently on course to strengthen relations with Russia through its Paks nuclear deal, which will be financed by the Russian state company Rosatom, offering a 10 billion euro credit line to Hungary for development. This will also wean Hungary further away from its EU financial dependencies.

The ever more Eurosceptic stance of Fidesz is also reflective of the equally conservative and nationalistic stance of the Hungarian majority. This is most reflected by the support given to Jobbik and its young energetic chairman, Gábor Vona, who, since the results of yesterday’s election, now leads the strongest radical right party in the European Union. Jobbik’s openly xenophobic stances and vocal questioning of EU membership has caused great concern for international as well as many domestic onlookers.

The EU continues to have very few measures installed to counter perceived ‘liberal backsliding’ within member states, usually resorting to economic sanctions or diminished voting powers. As Hungary becomes less financially dependent on ‘Western powers’ there will be less incentive for Fidesz to cater to EU directives that might go against the increasingly centralised and nationalistic path Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has for Hungary.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image Viktor Orbán, Credit: European People’s Party (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1lFDree

_________________________________

Erin Marie Saltman

Erin Marie Saltman

Dr Erin Marie Saltman works as a research project officer at the counter-extremism think tank Quilliam. She completed her PhD in Political Science at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES) at University College London (UCL) in 2013. Erin’s main topic of research focuses on the process of contemporary political socialisation in Hungary looking at youth activism and party alignment in a post-communist setting.

1 Comments