Latvia’s government collapsed at the end of 2013, with new elections scheduled to be held in October this year. Licia Cianetti writes that the country’s European Parliament elections are likely to be dominated by the national situation, with the results potentially giving an indication of where parties stand in the run up to October. She notes that the key issue for voters has been the legacy of austerity policies implemented by Latvia in the wake of the financial crisis, but that the campaign is also being fought against the backdrop of the Ukraine crisis given the large Russian population living in the country.

Latvia’s government collapsed at the end of 2013, with new elections scheduled to be held in October this year. Licia Cianetti writes that the country’s European Parliament elections are likely to be dominated by the national situation, with the results potentially giving an indication of where parties stand in the run up to October. She notes that the key issue for voters has been the legacy of austerity policies implemented by Latvia in the wake of the financial crisis, but that the campaign is also being fought against the backdrop of the Ukraine crisis given the large Russian population living in the country.

This year has so far been particularly intense for Latvian politics and will most likely continue to be. After the resignation of former Prime Minister Dombrovskis in late 2013, January saw the formation of a new government. This is headed by the former Minister of Agriculture Laimdota Straujuma and is based on the previous coalition (Dombrovskis’ right-of-centre Unity, former president Zatlers’ Reform Party, and the right-wing nationalist National Alliance) with the addition of the Union of Greens and Farmers (ZZS).

The latter is under the control of the multimillionaire mayor of Ventspils, Aivars Lembergs, and is one of the infamous parties of oligarchs that controlled Latvian politics until 2011 and whose corruption scandals led former president Zatlers to call for a referendum to disband the 2011 parliament. Once again the moderate Russophone party Harmony Centre, currently the biggest party in the Saeima (the Latvian parliament) with 31 seats out of 100, was excluded from the governing coalition.

The new government is slated to be in office only until the next parliamentary elections, scheduled for October this year. The elections to the European Parliament on 24 May are set to take place in this context of on-going political turmoil. All of the parties are likely to use the European election campaign in order to position themselves in view of the October parliamentary elections.

The European elections

Latvia will elect eight MEPs, with a proportional electoral system incorporating fixed party lists and a 5 per cent threshold. Polls put Harmony Centre at a clear advantage with around 35-40 per cent of the vote and three MEPs, which would mean doubling its results from 2009 (when it got 19.5 per cent of votes) and adding one MEP to its current two.

The other, more radical, Russophone party – For Human Rights in a United Latvia (FHRUL) – has not cleared the 5 per cent threshold in Saeima elections since 2010, but it secured EP representation with about 10 per cent of the vote and one MEP in 2009. However, this time MEP Tatjana Zhdanoka – who is very popular among Russophone activists in the Baltics at large and is again the leading candidate in FHRUL list – seems set to lose her seat. In the run up to the elections FHRUL can count on the support from the radical Russophone party Zarya (Za rodnoy yazik, For mother tongue), a controversial party born in the wake of the 2012 referendum on the status of Russian as a second state language. However, Zarya’s poor results in the 2013 Riga municipal elections suggest that this will not likely boost FHRUL’s results.

As for the governing parties, their fortunes in the EP elections are likely to be mixed. The Reform Party initially seemed unlikely to go beyond the 5 per cent threshold, however it has now announced its intentions to merge with Unity and is no longer filing a list for the EP elections. National Alliance (NA) is expected to increase its share of votes from 7.45 per cent in 2009 to 11 per cent. However, given the low number of seats to be distributed, this will still leave NA with only one MEP. The main governing coalition party, Unity, has seen a sharp decrease in popularity over recent years, but it is expected to retain two MEPs and gain somewhere in the region of 25 per cent of the vote. The polls also suggest that ZZS will confirm its return to the fore of Latvian politics with the EP elections. In 2009, at the centre of several corruption scandals, ZZS failed to meet the 5 per cent threshold; this year it is expected to gain around 17 per cent of the vote.

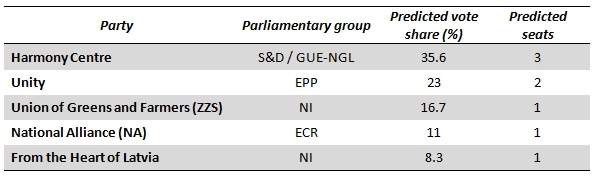

A new entry in the Latvian political landscape, “No sirds Latvijai” (From the Heart of Latvia), was created in January 2014 and seems set – according to recent polls – to get about 8 per cent of the vote and one EP seat. From the Heart of Latvia is led by Inguna Sudraba, the former Latvian State Auditor and the most trusted public figure in Latvia according to a 2013 poll. Her anti-corruption credentials are likely to attract the votes that had gone to the Reform Party before its collapse. The party platform’s focus on reclaiming Latvia from the politicians that have impoverished and disappointed their people might also attract a portion of the disaffected and anti-austerity vote. The table below shows the latest Pollwatch2014 predictions.

Table: Pollwatch2014 predictions for the European Parliament elections in Latvia

Note: Harmony Centre is an alliance of two parties – the Socialist Party of Latvia and the Social Democratic Party. Predictions are based on a poll from 6 April conducted by Faktu. Only parties predicted to get a seat are shown in the table. For more information on the parties see: Harmony Centre, Unity, Union of Greens and Farmers (ZZS), National Alliance (NA), From the Heart of Latvia.

The results of the EP elections should prove a good indicator of the parties’ relative power after the sudden changes of the past six months. The results will therefore in all probability help shape the parties’ strategy for the October general elections. Harmony Centre has a chance to further establish itself as a respectable, left-of-centre, mainstream party. NA is likely to keep its focus on ethnic and national issues; the perception of a “Russian threat” that the party typically plays up in its electoral campaigns may have some marginal added currency with the news coming from Ukraine.

After having lost the Riga municipal elections with a highly ethnic and nationalist campaign, Unity might use the EP electoral campaign to re-establish its image as a pragmatic, economically literate, competent party. Former PM Dombrovskis was also in the running to be the European People’s Party candidate for the post of EU Commission President, but lost out to Jean-Claude Juncker. As for ZZS, good results in the EP elections might seal its resurgence from the ashes of the 2011 anti-oligarch referendum, already heralded by its inclusion in the new government.

The campaign: austerity and ‘Latvia’s success story’

The main topic of discussion in the EP elections continues to be the legacy of Dombrovskis’ years of austerity. Heavily hit by the 2008 financial crisis, Latvia lost about a quarter of its GDP between 2007 and 2009 and was bailed out by the IMF. Dombrovskis responded to the crisis by implementing one of the most severe austerity programmes in Europe.

This included laying off one third of public employees and introducing steep wage cuts for the rest (30 per cent on average). Welfare provisions were also cut, hospitals were closed down, VAT was increased, the flat personal income tax went from 23 to 25 per cent, and the non-taxable minimum income was reduced from 90 to 45 LVL (for a recent analysis of the austerity measures and their consequences, see the Friedrich Ebert Foundation’s report).

The regressive impact of these measures was also noted by the IMF: while praising Latvia’s successful recovery, it warned against the risks of growing poverty and inequality. Indeed, notwithstanding positive GDP growth indicators, Latvia is experiencing high unemployment (14.9 per cent) especially among the youth (21.9 per cent). The country also has some of the lowest wages in Europe, has lost over 5 per cent of its population to emigration, has one of the highest income inequality rates in Europe, and, according to Eurostat data, 36.6 per cent of its population is at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Dombrovskis’ re-election in 2010 during the most severe period of cuts was interpreted as a general acceptance of the need for ‘harsh medicine’ for Latvia to recover, and prompted observers to remark on the Latvians’ tenacity and almost pride for collective hardship.

However, there are signs that this acceptance of austerity measures as an inescapable necessity might be waning. A public opinion poll showed that over half of Latvia’s inhabitants now judge the response to the crisis as “incorrect and even devastating”. A survey held just months before Dombrovskis’ resignation showed that 76 per cent of Latvians were critical of his governments’ performance. Dissatisfaction with severe austerity measures was also voiced by the Latvian Confederation of Employers and the Free Trade Union Confederation of Latvia.

In this context, Harmony Centre is the party best positioned to attract the votes of disillusioned Latvians. Although it is largely associated with the Russian-speaking minority, Harmony Centre is the only left-of-centre party in the Latvian party system and has consistently opposed the government’s austerity policies. Its EP elections slogan – “Latvia’s problem is not the Russians, Latvia’s problem is poverty” – clearly shows the party’s attempt at repositioning itself as social-democratic and at challenging ethnic readings of the Latvian party system.

Although Harmony Centre has started attracting a share of the ethnic Latvian electorate (at least in local elections), it remains to be seen whether it will be able to dispel its image as the “party of the Russians” and more strongly establish its credentials as the main representative of Latvia’s left. The EP elections will offer Harmony Centre the opportunity to strengthen those credentials ahead of the October parliamentary elections.

Euroscepticism is not a major feature of Latvia’s EP election debate

The adoption of the euro in January this year, against the opinion of the large majority of Latvians who were negatively disposed towards it, could have been an occasion for Eurosceptic parties to emerge or for some of the existing parties to use Eurosceptic rhetoric to their advantage. However, this was not the case. The parties that were in opposition when the country opted to join the single currency – Harmony Centre and ZZS – were sceptical about the timing of the decision, but not necessarily its substance.

Harmony Centre was in favour of joining the euro, but criticised the government for having rushed the decision to enter the Eurozone in 2014 without an open discussion about the pros and cons of such a move. Moreover, Harmony Centre’s party programme is openly pro-EU and has a long section on the need for further European integration. ZZS was more vocal against joining the euro and in August 2013 even presented a bill to keep the national currency until 2019. Apart from this, however, the party has not deployed a recognisably Eurosceptic rhetoric.

Even the nationalist NA constructs its national discourse in opposition to the East rather than to the EU. This means that they strongly support EU membership, were in favour of entering the Eurozone, and so far have not used the Eurosceptic discourse typical of other nationalistically minded parties in other EU countries. Thus, no major party seems inclined to run a Eurosceptic campaign. One small and widely unknown party, “Sovereignty”, has registered a list based on an anti-capitalist, anti-EU, anti-inequality platform. Although some of its claims might resonate with an impoverished and disillusioned population, it seems unlikely that this small party will have enough visibility to become a relevant player in the elections.

Therefore, barring unexpected developments in the next couple of weeks, Euroscepticism should not be a major feature of the Latvian campaign. Rather, parties will continue to conduct their campaigning with an eye to the upcoming parliamentary elections. The EP elections will be part of the prolonged electoral campaigning that started with the formation of the new government and will culminate in the vote in October. Latvia’s economic policy is at the centre of the debate, but the events in Ukraine also have some relevance as they offer an opportunity to discourage ethnic Latvian voters from trusting the “Russian” Harmony Centre. In any case, the elections will provide an occasion for parties to test their campaigning strategies and to gauge their relative power.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1j2DyMx

_________________________________

Licia Cianetti – University College London

Licia Cianetti – University College London

Licia Cianetti is a PhD student in the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London. Her primary research interests are in minorities, democratic representation and power. Her PhD research concerns the political representation of Russian-speaking minorities in Latvia and Estonia and their access to the policy making process.

1 Comments