In Italy’s European Parliament elections Matteo Renzi’s Democratic Party received over 40 per cent of the national vote, with Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement finishing in second place on just over 20 per cent. Roberto Orsi assesses what the elections mean for Italy’s political landscape. He notes that while Renzi has attempted to portray the country as simply requiring a number of piecemeal reforms to solve existing problems, Grillo has adopted a far stronger stance, arguing for a period of deep and fundamental reconstruction. While the European election results were perhaps not surprising given Renzi’s current public image, long term it may be difficult for Grillo to win widespread support for this vision.

In Italy’s European Parliament elections Matteo Renzi’s Democratic Party received over 40 per cent of the national vote, with Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement finishing in second place on just over 20 per cent. Roberto Orsi assesses what the elections mean for Italy’s political landscape. He notes that while Renzi has attempted to portray the country as simply requiring a number of piecemeal reforms to solve existing problems, Grillo has adopted a far stronger stance, arguing for a period of deep and fundamental reconstruction. While the European election results were perhaps not surprising given Renzi’s current public image, long term it may be difficult for Grillo to win widespread support for this vision.

The European election results in Italy were rather surprising. In the context of today’s three-party political landscape (the centre-left Democratic Party, Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement, and Berlusconi’s Forza Italia), most pre-vote polls indicated a rise of Grillo’s movement, closing in on current PM Matteo Renzi’s Democratic Party, with Berlusconi’s faction below 20 per cent. Instead, the results were surprisingly in favour of the ruling establishment, while Grillo has suffered a defeat which, while not so substantial in terms of sheer numbers, entails a deep political cost.

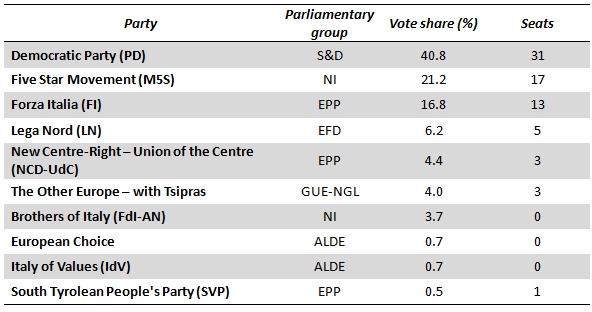

Grillo himself appeared confident that his movement might become the first party in Italy. However, the Democratic Party reached 40.8 per cent, against 21.2 per cent for the Five Star Movement, and a meagre 16.8 per cent for Berlusconi. Lega Nord, which has been recovering from a series of scandals and electoral defeats, scored 6.2 per cent at the national level. The Table below shows the overall results in Italy.

Table: Result of the 2014 European Parliament election in Italy

Note: For more information on the parties, see: Democratic Party (PD); Five Star Movement (M5S); Forza Italia (FI); Lega Nord (LN); New Centre-Right (NCD); Union of the Centre (UdC); The Other Europe – with Tsipras; Brothers of Italy (FdI-AN); European Choice; South Tyrolean People’s Party (SVP). European Choice is an electoral list centred around the Civic Choice party. Italy’s electoral law guarantees that one seat goes to the German speaking minority in South Tyrol – this seat was taken by the South Tyrolean People’s Party. Other parties with low vote shares are not shown in the Table.

There are several lessons which can be drawn from these results. The first one is the slow but constant decline of Berlusconi’s party and his personal power. Since Berlusconi stepped down as PM in the dramatic days of a financial tempest in November 2011, apparently under unprecedented international pressure, he has been convicted for fiscal evasion, deprived of his passport and expelled from the Parliament.

More remarkable is the Renzi-Grillo contest, which was the central question in the EU election for Italy. While Grillo has presented this vote largely as a political test for the current government, Renzi has clearly managed to overcome the hurdle with stunning success. The Democratic Party had indeed never attained such a percentage of the vote, and even considering the relatively low electoral turn out, down to 58.7 per cent from 66.4 per cent in 2009, it was a spectacular victory. There may be several reasons why so many Italians decided to back Renzi.

First, it has to be noted that Renzi enjoys the unanimous and almost uncritical backing from the mainstream press, to the point of embarrassing cult-of-personality-like articles, a mix of former Eastern bloc techniques and post-modern, multiculturalist and kitsch content. More importantly, the whole Renzi government, in charge now for little more than three months, has been successfully engineered as a public relations operation, in order to provide a new row of frontline faces to the same policy line, as Monti and Letta rapidly became too unpopular. Renzi, albeit belonging to the same political area and being connected to the same prominent allies both at home and abroad, has constructed over the years an image of homo novus, which, despite its disputability and long-term fragility, was enough to gain the vote of many citizens, exhausted from the political and economic situation and inclined to accept any appearance of “change”.

While both Grillo and Renzi insist on the unavoidability of such “change”, their narratives thereof are very different. For Grillo, the country is already hopelessly bankrupt, and it has consequently to look beyond the current disaster to a period of deep and painful reconstruction. For Renzi and the Democratic Party, Italy is a “great country” with a series of problems, which can nevertheless be solved through a number of moderate (to the point of cosmetic) slow-motion “reforms”. But overall, their narrative is that the country is fundamentally fine as it is at present. Indeed, the Democratic Party has presented the electoral contest as one between “fear” and “hope”.

Not surprisingly then, the majority of Italians, who remain moderate (also because of demographic reasons), have preferred Renzi’s promise of slow, almost imperceptible reforms which would gradually lift the country out of today’s predicament, without any serious challenge to the status quo. The Democratic Party’s message was certainly appealing to its core electoral base (pensioners, public employees), to the elderly, and more in general to those who intend to defend their current socio-economic position in the face of the most serious crisis to occur in Italy during peacetime.

On the other hand, Grillo’s alarming tones – albeit certainly reflecting the anger of the non-guaranteed, particularly the younger generation and a large part of the small business owners, who are bearing the brunt of the crisis’ costs – proved unpalatable to most voters. Grillo’s campaign was also excessively polemical to the point of hysteria. More importantly, though, his diagnosis and vision of the country’s future is simply too bitter to accept, even if arguably closer to the reality than Renzi’s. It requires an almost heroic ethical stance, which is unlikely to be prevalent in Italy.

This can actually be Grillo’s main political problem: while his project is squarely grounded in the idea of mobilising the Italians for the sake of national reconstruction (even without nationalism), he may well realise that such mobilisation is not attainable in the way and duration he wishes. More broadly, the whole idea of radically changing the country “from below” appears historically and politically weak, as the Italians and their prevalent political culture, as already argued in this blog, are actually the problem, and not the solution.

While in theory the exponential economic and social damage caused by the crisis should favour Grillo in the long run, revealing how the country is indeed so greatly compromised that any talk of “recovery” coming from the establishment is pure nonsense; Grillo may never see a historic turn in the direction he is favouring, as more and more Italians, especially those unable to emigrate, will fatalistically surrender to a narrative of a present and a future which embrace degradation and steep decline as the way forward. Indeed, if that is to appear as the “unavoidable” direction of events, it seems certainly easier to accommodate such a trajectory, rather than to fight it. Those who are too ambitious to accept the end result of such a process may well leave the country, as is already happening.

This article originally appeared at the LSE’s Euro Crisis in the Press blog

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1p6jXBf

_________________________________

Roberto Orsi – University of Tokyo

Roberto Orsi – University of Tokyo

Dr Roberto Orsi is a co-investigator on the Euro Crisis in the Press project. He holds a PhD in International Relations and is currently Project Assistant Professor at the Policy Alternative Reasearch Institute (政策ビジョン研究センター) of the University of Tokyo (Japan). His research interests focus on international political theory, history of ideas (particularly modern continental political philosophy and critical theory), political theology (Carl Schmitt). He is also interested in social science epistemology and classical philology.