Poland is due to hold parliamentary and presidential elections in 2015. Aleks Szczerbiak writes on the emergence of the anti-establishment Congress of the New Right (KNP) party, which gained the fourth largest share of the vote in the country’s European Parliament election in May. He argues that while the party’s performance will give it a platform to build on for next year’s elections, long-term it could suffer from the same problems as previous anti-establishment parties in Poland whose support evaporated fairly quickly after initial success.

Poland is due to hold parliamentary and presidential elections in 2015. Aleks Szczerbiak writes on the emergence of the anti-establishment Congress of the New Right (KNP) party, which gained the fourth largest share of the vote in the country’s European Parliament election in May. He argues that while the party’s performance will give it a platform to build on for next year’s elections, long-term it could suffer from the same problems as previous anti-establishment parties in Poland whose support evaporated fairly quickly after initial success.

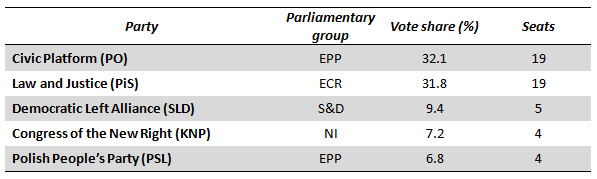

Much of the media commentary on the May 2014 European Parliament (EP) elections focused on the apparent strong showing of anti-establishment parties such as the Front National, the UK Independence Party, the Danish People’s Party and Syriza in Greece. The European election in Poland also saw the emergence of a new radical challenger party, the Congress of the New Right (KNP), which appeared to come from nowhere to finish fourth with 7.2 per cent of votes and win 4 out of the country’s 51 MEPs, as shown in the Table below.

Table: Result of the 2014 European Parliament election in Poland

Note: Only those parties which won a seat are shown. For more information on the groups in the European Parliament see here. For more information on the parties see: Law and Justice (PiS); Civic Platform (PO); Democratic Left Alliance (SLD); Congress of the New Right (KNP); Polish People’s Party (PSL).

In spite of its leader’s numerous controversial statements, the Congress emerged as the most effective vehicle for protest voters, mobilising the frustrated Polish intelligentsia and younger voters around a programme of radical economic liberalism and hostility to the EU. Its election success will provide the party with political momentum over the next few months but its controversial leader is too wilfully provocative, and support base almost certainly too unstable, for it to be anything more than a fleetingly successful but short-lived protest party.

A controversial political veteran

Formed in March 2011, the Congress is the latest project of Janusz Korwin-Mikke, one of its four new MEPs and a veteran eccentric of the Polish political scene who has contested every Polish national election since the collapse of communism in 1989. Many prominent members of other parties – including Civic Platform (PO), the centrist grouping led by prime minister Donald Tusk that has been the main governing party in Poland since 2007 – began their political careers as members of the Real Politics Union (UPR), Mr Korwin-Mikke’s first political party in which he played a leading role until he resigned in 2009. Some commentators have quipped that if everyone who had ever a member of the Real Politics Union joined the same party it would probably be the largest in Poland, and if all those who ever voted for Mr Korwin-Mikke did so at the same election then he would easily win!

In fact, until the recent EP poll, he only had one brief stint in the Polish parliament, at the beginning of the 1990s before the 5 per cent electoral threshold for securing parliamentary representation was introduced. However, Mr Korwin-Mikke’s fortunes began to look up in the June/July 2010 presidential election when, although only securing 2.5 per cent of the votes, he finished fourth ahead of Waldemar Pawlak the then deputy prime minister and leader of the Polish Peasant Party (PSL), Civic Platform’s junior coalition partner since 2007.

Mr Korwin-Mikke is one of the most controversial figures in Polish politics. Right-wing conservative politicians, particularly those from the post-communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, have often fallen foul of the West European liberal cultural and political establishment, but Mr Korwin-Mikke goes way beyond this and is in a league of his own as far as political incorrectness is concerned. During the EP campaign, for example, he appeared to: agree with Russian President Vladimir Putin that Poland had trained ‘Ukrainian terrorists’ who took part in the demonstrations that led to the downfall of the country’s previous pro-Moscow government; claim that there was no proof that Adolf Hitler was aware of the Holocaust; and argue that the difference between rape and consensual sex was very subtle, implying that some apparent victims actually wanted to have intercourse.

Previously, he questioned whether women should vote in elections given that they were less interested in politics and supported higher welfare spending; although his supporters argued that, as a declared monarchist, Mr Korwin-Mikke was actually in favour of depriving every one of the right to vote! On another occasion, criticising the Paralympics, he argued that in order for humanity to flourish, people needed to watch ‘healthy, beautiful, strong, honest and intelligent people’ on TV rather than invalids.

A repository for ‘Generation Y’ protest voters?

However, this string of controversial statements by the party’s leader did not appear to harm the Congress’s electoral prospects in the EP poll. Indeed, if anything it reinforced Mr Korwin-Mikke’s credentials as a ‘political outsider’ and helped his party to emerge as the most attractive repository for protest voters looking for a radical alternative to the political establishment. Such voters often play a disproportionate role in ‘second order’ elections such as EP polls, where turnout is traditionally much lower than in national elections, and Mr Korwin-Mikke was thus able to mobilise his relatively small but extremely loyal following successfully (some commentators earlier doubted whether they would actually come out to vote). In the context of a 22.7 per cent turnout in Poland – the third lowest among the 28-member EU bloc and much lower than the 47.5 per cent average recorded in post-1989 Polish parliamentary elections – these voters provided the Congress with the basis for a respectable EP election result.

Moreover, although Mr Korwin-Mikke is 72 years old, the Congress of the New Right enjoyed particularly high levels of support among younger voters. According to the exit poll conducted by the Ipsos agency, the Congress secured 28.5 per cent of 18-to-25-year-old voters – more than any other party – and these comprised half of the party’s supporters (overall three-quarters of its voters were under 40-years of age). Although more data and empirical analysis is required before more definitive judgements can be made about the party’s demographic profile, some sociologists have argued that many of these voters are drawn from what social commentators sometimes refer to as ‘Generation Y’: the large numbers of young and fairly well-educated unemployed in Poland who live at home with their parents and are frustrated that Poland is not developing more rapidly and with the apparent ‘glass ceiling’ of vested interests and corrupt networks that stifles opportunities for them.

These young people often face a choice between moving to take jobs abroad that fall well short of their abilities and aspirations or remaining in a country which they feel offers them few prospects for the future. These younger voters – who spend much of their time on the Internet, which is their main source of political information rather than the traditional broadcast and print media – also helped to give the Congress a very strong on-line presence; Mr Korwin-Mikke’s Facebook page, for example, has nearly 400,000 ‘likes’.

More broadly, the Congress of the New Right appeared to tap into what sociologists have termed the ‘frustrated intelligentsia’: fairly well-educated Poles, sometimes running small businesses, who blame the deadweight of state bureaucracy, excessive regulation and red tape, high taxes, vested interests and cronyism for blocking individual freedom and initiative, thus preventing them from realising their professional and career ambitions. For example, 16.6 per cent of managers and specialists and 13.4 per cent of private entrepreneurs voted for the Congress in the EP poll. Moreover, many of these voters also increasingly see the EU as the embodiment of a stifling bureaucracy and political and cultural oppression rather than symbolising the civilisation progress and socio-economic modernisation and solidarity that Poles were promised at the time of accession to the Union.

Radical economic liberalism is the core

The Congress of the New Right is an economically libertarian and socially conservative party, but the core of the party’s programme, and main driver of its support, is its radical economic liberalism. The Congress opposes all but the most minimal form of state intervention in, and regulation of, the economy, which, it argues, stifles opportunities for the most dynamic sections of Polish society. Mr Korwin-Mikke’s party supports the abolition of income tax and slashing other tax rates, together with radical and far-reaching privatisation and government expenditure cuts, leaving only a residual and massively slimmed-down public sector.

The party combines this with a traditionalist conservative stance on some social and moral-cultural issues: for example, favouring a tough approach to law and order and the restoration of capital punishment, while opposing same-sex marriage. However, the Congress also supports some social libertarian policies, such as the legalisation of cannabis, and does not have the same high profile commitment to Christian values and promoting policies rooted explicitly in the Catholic Church’s moral and social teaching, which has, to a greater or lesser extent, been the hallmark of almost every other Polish centre-right party.

Rather, the party argues more generally that Polish laws should be underpinned by the norms and principles of ‘Latin civilisation’. Interestingly, 20 per cent of those who voted for the Palikot Movement (RP) – a liberal, but also strongly anti-clerical, protest party that came from nowhere to finish third in the most recent 2011 parliamentary election, winning 10 per cent of the vote – switched to the Congress of the New Right in the 2014 EP poll. The Congress is also a radically Eurosceptic party, with Mr Korwin-Mikke arguing that half of the current EU Commissioners should be arrested, and promising to ‘blow up the EU from within’ and turn the European institution buildings into a brothel.

A flash in the pan?

As far as the Congress’s future prospects are concerned, the party’s relatively strong EP election showing will certainly give it a higher media profile over the next few months that could carry it through to relative success in the summer 2015 presidential and autumn 2015 parliamentary elections. Mr Korwin-Mikke will use his new EP platform to continue to make controversial statements and outspoken attacks on the EU that will no doubt delight his most dedicated supporters and get thousands of ‘hits’ on Internet sites like YouTube.

However, although at the time of writing it is unclear which of the Eurosceptic European party groupings the Congress will choose to align itself with, Mr Korwin-Mikke will also be an extremely marginal, maverick voice in the EP. His often-wilfully outrageous statements will limit his ability to attract the support beyond the party’s core that it needs to make a real breakthrough, and he may eventually also prove too much for all but his most committed supporters. In addition to straightforward rebuttal and trying to contextualise his remarks, these are often forced to defend Mr Korwin-Mikke’s more controversial claims by (not very convincingly) distinguishing between their leader’s personal opinions and the party’s official stance.

Moreover, the Congress’s anti-establishment protest electorate is an impulsive and unstable one. Even if the party is able to retain this support for a period, it could evaporate very quickly. While the Congress of the New Right will undoubtedly benefit in the short-term from the political momentum derived from its EP success, there is, therefore, every chance that it could prove yet another flash-in-the-pan and join the long list of fleetingly successful but relatively short-lived anti-establishment protest parties that have been a recurring feature of the post-communist Polish political scene.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image: Polish Parliament, Credit: (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1pAILBE

_________________________________

Aleks Szczerbiak – University of Sussex

Aleks Szczerbiak – University of Sussex

Aleks Szczerbiak is Professor of Politics and Contemporary European Studies and Co-Director of the Sussex European Institute (SEI) at the University of Sussex. He is author of Poland Within the European Union? New Awkward Partner or New Heart of Europe? (Routledge 2012) and blogs regularly about developments on the Polish political scene at http://polishpoliticsblog.wordpress.com/