Most coverage of the European Parliament elections has noted the rise of several far-right and Eurosceptic parties across Europe. Cas Mudde argues, however, that a more important trend was toward increasingly fragmented party systems. Presenting a series of numbers from the elections, he illustrates that ‘big parties’ are experiencing declining vote shares, with a greater number of smaller parties now competing for power in many EU countries.

The 2014 European elections have led to a surprising amount of media attention and speculation. The dominant frame, which had been decided upon well before the actual results came in, is that “the far right” or “Euroscepticism” has won the elections. In fact, we are told that there has been an “earthquake” that has led to “concerns in Europe”. The new European Parliament will “struggle to find majorities”, divided as it is between a Pro-EU and an anti-EU camp.

But behind this simplistic and sensationalist narrative lays a deeply fragmented reality of a European Parliament with over 100 national parties. In many ways, this reflects an ongoing trend of fractionalisation in national party systems, in which big parties are shrinking, or even disappearing, the number of represented parties is growing, and turnout is (on average) dwindling.

I’ll present some of these trends in a set of remarkable numbers from the 2014 European elections. I have not systematically compared them to similar numbers in the 2009 European elections or the last national parliamentary elections. My hunch is that the 2014 European elections continued a broader trend, but with important national and, to some extent, regional differences. The biggest shocks were in Southern Europe and Western Europe, while Eastern Europe was remarkably stable on average.

Medium (M) is the new large (L)

Scholars started to note the decline of the Grand Old European parties in the 1980s, but it has become particularly visible in the 21st century. Given that one of the golden rules of second-order elections is that “big parties lose”, we wouldn’t expect too many big parties in the 2014 European elections. And this was exactly what happened, but to an even larger extent than previously.

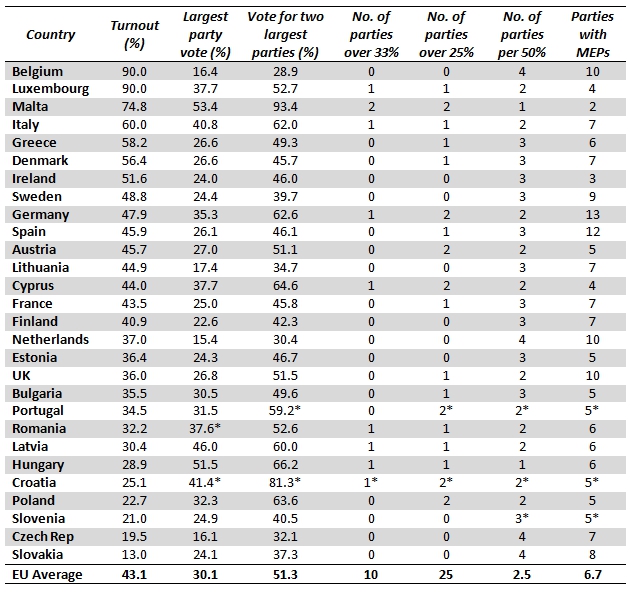

The highest percentage of votes received by a single party in any country during the 2014 European elections was 53.4 per cent. With it, the Maltese Labour Party (PL/MLP) was only one of two parties to get a majority of the vote; the other one was Fidesz with 51.5 per cent in Hungary. Perhaps even more striking, in just three other countries did the biggest party get more than 40 per cent: the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) with 41.4 per cent in Croatia, the Democratic Party (PD) with 40.8 per cent in Italy, and Unity (V) with 46 per cent in Latvia. In all cases the parties were either current (HDZ+) or former electoral alliances that had since merged into one political party (PD and V).

The lowest percentage of the vote received by the largest party in a country was 15.4 per cent. Surprisingly, it was in the Netherlands and not Belgium, despite the fact in the latter country no political party contests elections throughout the whole territory! In a total of four countries the biggest party attracted less than 20 per cent of the vote.

In only one country did two parties gain more than 33 per cent of the vote each: Malta, the last remaining two-party system in the European Union. In a staggering two-thirds of the twenty-eight EU member states not one party was able to win at least one-third of the vote, while in a quarter of the countries the biggest party attracted less than one-quarter of the votes, as shown in the Table below.

Table: Turnout and party statistics at the 2014 European Parliament elections

Note: Figures marked with * indicate that at least one of the parties involved is an electoral coalition. The figures in the “No. of parties per 50%” column indicate how many parties are required to add up to a vote share greater than 50 per cent (based on the largest vote shares). Source: Website of the European Parliament

A fragmented European Parliament

The two largest political groups in the European Parliament – the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) – hold a combined 411 seats. While a decrease of 59 MEPs, though in a slightly smaller parliament, it gives the two strongly pro-EU groups a majority of 54.7 per cent of the seats – 6.7 per cent less than in the previous parliament. However, it can count on the support of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats in Europe (ALDE), which has been reduced to 59 seats (from 83), in virtually all important decisions.

The total number of political parties that elected representatives to the 2014-2019 European Parliament was 186. This is 16 higher than after the 2009 elections. It should be noted that several of these parties are in fact electoral coalitions, so the actual number of parties with MEPs will probably be around 200.

The largest number of seats for any individual party was 43, although technically the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) is in a coalition with the Christian Social Union (CSU), its more conservative Bavarian counterpart. It is thereby 12 seats bigger than the second-biggest faction, that of the Italian Democratic Party (PD), but eight seats smaller than it was in the last legislature – it should be noted that the 2014-2019 European Parliament is 15 seats smaller than its predecessor.

The number of new parties in the 2014-2019 European Parliament is 37. Although twenty member states saw a new party enter the EP, Germany alone accounted for eight (21.6 per cent), a consequence of the Constitutional Court’s decision to strike down the electoral threshold of 3 per cent. By far the biggest new party is Italy’s Five Star Movement (M5S), which gained 17 seats.

The number of parties that lost representation in the European Parliament was 21. Interestingly, given that narrative of the “earthquake of far right success,’ no less than five far right parties lost representation: Ataka (Bulgaria), the British National Party, Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS), the Greater Romania Party (PRM), and the Slovak National Party (SNS). The biggest number of seats was lost by Italy of Values-List Di Pietro (7), while the Austrian single-issue Hans-Peter Martin’s List ‘lost’ the largest percentage of votes (17.7) by not contesting the 2014 elections. Incidentally, 21 is also the highest number of seats gained by any party. This honour went to the French Front National (FN), which no newsreader could have missed.

The number of countries in which no seat changed hands was 2: Cyprus and Luxembourg. In two more, only one seat moved from one party to another (Estonia and Malta), while in three others just two seats moved (Finland, Latvia, and Netherlands). The case of the Netherlands is particularly striking, as it is a medium-sized member state with a total of 26 seats and a highly fragmented party system (see below).

Balkanised national party systems

The highest percentage of the vote gained by two parties in a single country was in Malta, where the two biggest parties together gained 93.4 per cent of votes. The second-highest percentage, 81.3 per cent in Croatia, was the combined results of two electoral coalitions: one of two parties and one of five. In the other eleven countries in which the two biggest parties together got a majority of the votes, it was between one-half and two-thirds. Not only has the biggest party become at best medium-sized, the two biggest parties together attracted a majority of the votes in just 13 EU states (46 per cent). Moreover, in most of these 13 cases at least one of the two parties is either a current or former electoral alliance.

The average number of parties which had MEPs elected per country across the EU was 6.7. This ranges from just two in Malta to thirteen in Germany. Of the other four countries with a double-digit number of represented parties, the Netherlands was the only one without regional parties: i.e. parties with a regionally highly concentrated electorate.

The average number of parties needed to represent a majority of voters in a country was 2.5. The range is from one to four with a plurality requiring three – remember that in many countries this includes at least one current or recent electoral coalition. Of the four countries requiring four parties for a majority of the vote share, Slovakia is the only one with a biggest party of over 20 per cent of the votes. Lithuania, on the other hand, is the only country with a biggest party of less than 20 per cent that requires just three parties.

Twisted turnout

The turnout in Greece was 58.2 per cent, which was above the EU average, but shockingly low for a country that actually has compulsory voting (although no longer enforces sanctions). Greece had a lower turnout than Malta, which never had compulsory voting, and Italy, which abolished compulsory voting in 1993. The two other countries with compulsory voting, Belgium and Luxembourg, still hit 90 per cent turnout.

Slovakia experienced the lowest turnout ever recorded in a European election, at only 13 per cent. The country had a turnout of 59.1 per cent in its parliamentary election two years ago. It was less than a third of the EU average and exactly two-thirds of the second-lowest turnout, which was, interestingly, in the Czech Republic.

Finally, there were 8 countries in which the biggest party gained a higher percentage of the vote than the percentage of turnout in the country. Not surprisingly, all countries were in Eastern Europe, although in two the biggest party was an electoral coalition. Slovakia even had two parties with a higher percentage of the vote than national turnout!

In the end, these numbers confirm the trend in European politics toward highly fragmented party systems with 2-3 medium-sized parties surrounded by 3-5 smaller parties. The multiparty systems are increasingly in flux, so much so that the two big parties change regularly. Flash parties emerge with an ever bigger bang, while party mergers have become much more significant than significant splits. Even though the 2014 European elections were once again second-order elections – with big parties losing, small parties winning, and low turnout (although governmental parties seemed to have done fairly well) – these trends can be observed in first-order elections too.

The end of the big parties has so far received relatively little attention, being pushed to the sidelines by the flashier rise of new and ‘extreme’ parties. Its ramifications are more profound, however, at least in the short to medium term. Smaller parties lead to more difficult coalition formation processes, which can weaken government performance, and cause rising dissatisfaction and protest voting. Such processes can already be observed in Belgium and the Czech Republic, while the Netherlands requires more and more creative short-term alliances to keep its governments in power. Perhaps that should be one of the major national lessons of the European elections.

*The counting of anything in European elections or the European Parliament is a highly complex and frustrating activity. Parties change names, merge and split, or emerge into the spotlight from the amorphous “others” category. All the presented numbers are presented in the naïve understanding that they are correct.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

So? After all this upheaval, there are the same seven alliances in the European parliament, of which at least 5 will get group status and 1-2 will struggle. And if at least one of the two manages it, then we’ll probably see a reduction in the number of NI.

In other words, the larger number of parties has no problem building alliances, which makes the narrative more parties = less effective decision-making simply unsustainable.