Trade between Germany and China has increased substantially over the last decade. Emanuele Schibotto writes on the relations between the two countries and whether they now constitute an emerging ‘special relationship’ with implications in areas beyond trade, such as foreign policy, human rights and energy. He argues that a closer relationship with Germany could reduce China’s dependence on its traditional trade partners, including the United States and Japan.

Trade between Germany and China has increased substantially over the last decade. Emanuele Schibotto writes on the relations between the two countries and whether they now constitute an emerging ‘special relationship’ with implications in areas beyond trade, such as foreign policy, human rights and energy. He argues that a closer relationship with Germany could reduce China’s dependence on its traditional trade partners, including the United States and Japan.

Since the resumption of diplomatic ties in 1982, Germany favoured the “business first” policy towards China. From the small and medium-sized companies (the so-called Mittelstand) to multinationals, Corporate Germany understood long before its European competitors the business opportunites offered by emerging economies – with China being the first and biggest bet.

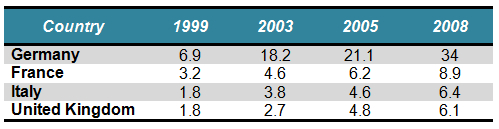

German pragmatism paid off. From 1995 to 2010, German exports increased sevenfold whereas its imports of Chinese goods increased by 800 per cent. Since 2002, China is Germany’s second main export destination outside Europe. In 2009 China became Germany’s first supplier and it is now its third largest trading partner, with bilateral trade volumes exceeding 140 billion euros in 2011. Today Berlin accounts for more than 25 per cent of China’s total trade with Europe. It is without doubt the most influential European player in China. The Table below shows the growth in German exports to China in relation to other states in the EU.

Table: Value of exports to China from selected EU states (billion euros)

Source: Eurostat

Further enhancing economic relations with China is instrumental to Germany for three main reasons. Firstly, Berlin’s goal is to boost trade flows with non-European countries in an effort to diversify export destinations and hold a strategic presence in one of the most dynamic regions of the globe. A recent Asian Development Bank report estimates that Asia’s contribution to world GDP will top 50 per cent by 2050. German companies still depend massively on Europe – over 70 per cent of their exports are shipped to European countries, whereas 7 products out of 10 imported by Germany come from the Old Continent. However, this is changing fast. If bilateral trade relations were to continue at the current pace, then Beijing would become Germany’s number one trading partner by 2020.

Secondly, China is deemed fundamental to keep Germany manufacturing primacy. German firms foresaw Beijing’s preminent role in the global supply chain years before their rivals. Volkswagen is a typical case. One of the first international automakers to venture into China, Volkswagen first took contact in 1978 as the Chinese government decided to open up to foreign enterprises under Deng Xiaoping. In 1984 it established the Shanghai – Volkswagen Automotive Company joint venture. The following year production started. China is now the Volkswagen Group’s largest sales market with a share of 20 per cent of the passenger car market and sales of 2.8 million vehicles in 2012. “We have always assumed that growth won’t occur primarily in Europe, but in China, Russia and in South and North America”, Volkgwagen Group CEO Martin Winterkorn said in an interview this year with Spiegel.

Along with Volkswagen there are over 2,400 companies operating in China, the majority of which are medium-sized or small, making the country the top foreign investment destination for German companies. Corporate Germany not only saw China as the world’s factory, rather it undertood its huge potential as a consumer market. The number of cities with more than a million residents is set to double by 2025 – from 120 to 240. According to McKinsey, by 2022 more than 75 per cent of China’s urban consumers could earn as much as Italy’s (in purchasing-power-parity terms).

Thirdly, the German government eyes the growing interest of Chinese investors in Europe. Over the past 10 years the number of transactions between Chinese and European companies has more than tripled. In 2013 alone investors from the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong have taken over 120 companies and shareholdings in Europe. “Chinese companies create jobs when they invest in Germany, and are very welcomed,” said German Economy and Energy Minister Sigmar Gabriel when celebrating the opening of the new Chinese Chamber of Commerce in Germany this year.

According to China’s Ministry of Trade, Germany is the European country with the best investment opportunities. China is the second largest non-European investor in Germany after the United States. Investments are piling up. Sany, a Chinese multinational heavy machinery manufacturing company, acquired German mid-sized company Putzmeister, a leading manufacturer of concrete pumps. Lenovo took over the electronics company Medion. Weichai Power bought a stake in Kion, the largest forklift truck maker in Europe. The Chinese Central Bank, through the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, has acquired a 3.04 per cent stake in Munich Re, a world leading reinsurer. According to data provided by the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, more than 2,000 Chinese companies are operating in Germany and had invested 2.7 billion euros by September 2013.

This emerging special relationship is mutually beneficial for China. Berlin is the country’s strategic foothold in Europe, with Chinese companies gaining insights into European markets. Furthermore, the presence of high-tech German companies on Chinese soil and Chinese-German scientific and academic collaboration help the Asian giant advance on the tecnology frontier. Industries such as automotive, pharma, renewables and high-technology in which Germany is a world champion are all considered strategically vital by Chinese political and economic leaders. Germany is not only China’s number-one trade partner in the EU, it is also the only country to collaborate with Beijing on its space programme. Finally, as Germans continue to import ever more goods, China’s dependence on its traditional trade partners – the United States and Japan – is progressively decreasing.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: Peter F. (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/WcogBs

_________________________________

Emanuele Schibotto

Emanuele Schibotto

Emanuele Schibotto is a PhD candidate in Geopolitics at the Guglielmo Marconi University in Rome, Editorial Director of the Italian think thank on International Relations Equilibri.net, Director for Development at the Asian Century Institute, and Business Development Manager for the international language consulting firm Maka.