Slovenia held parliamentary elections on 13 July. Alenka Krašovec and Tim Haughton assess the results of the election, which saw a newly formed party led by Miro Cerar win the largest share of the vote. They write that the key challenge for Cerar will be to retain his new party’s appeal while making the tough decisions necessary to solve the country’s economic problems.

Slovenia held parliamentary elections on 13 July. Alenka Krašovec and Tim Haughton assess the results of the election, which saw a newly formed party led by Miro Cerar win the largest share of the vote. They write that the key challenge for Cerar will be to retain his new party’s appeal while making the tough decisions necessary to solve the country’s economic problems.

Parliamentary elections and party politics in Slovenia are becoming predictable in their unpredictability. For the first two decades of the country’s independence, party politics was largely stable. True, in the second decade the once mighty force of Slovene politics, Liberal Democracy, saw its support drop, the Social Democrats emerged as a powerful force, but only really for one election in 2008, and there were a stream of new parties. Nonetheless, in a region marked by high levels of electoral volatility, Slovenia appeared to be more stable than most.

All that changed in December 2011 when early elections (provoked by the disintegration of a coalition) witnessed two parties formed just weeks before the polls garner 37 per cent of the vote. Three-and-a-half years on, another early election provoked by a battle over the leadership in the biggest governmental party, Positive Slovenia, and the disintegration of the governing coalition, saw one new party – Miro Cerar’s Party – formed just over a month before the polls scoop nearly 35 per cent of the vote.

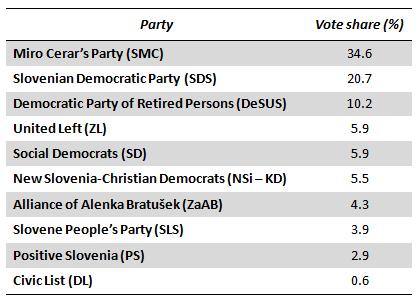

Central to explaining the outcome of the 2014 elections and the twists and turns of party politics in Slovenia during the preceding parliamentary term are novelty, corruption and expertise. The Table below shows the final vote shares for each party in the elections.

Table: Vote shares in the 2014 Slovenian parliamentary elections

Note: Figures from Electoral Commission. For more information on the parties see: Miro Cerar’s Party (SMC); Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS); Democratic Party of Retired Persons (DeSUS); United Left (ZL); Social Democrats (SD); New Slovenia-Christian Democrats (NSi – KD); Alliance of Alenka Bratušek (ZaAB); Slovene People’s Party (SLS); Positive Slovenia (PS); Civic List (DL).

Of the 17 parties which contested the election, seven entered parliament. At the time of writing, it remains unclear whether the Slovene People’s Party (SLS) (with a pedigree stretching back to 1988 before the break-up of Yugoslavia), will cross the 4 per cent electoral threshold. When the results were announced on election night, the party had garnered 3.97 per cent of the vote. Definitive results, however, will be published later in the month once all of the postal ballots have been counted. Given past experiences, the chances of the Slovene People’s Party crossing the threshold look slim.

Three and a half years of political turmoil

Although winning a plurality of the vote in the 2011 elections, Positive Slovenia (PS) and its colourful leader founder, Zoran Janković, who had built a reputation as a ‘man who gets things done’ as the boss of Slovenia’s dominant retailer Mercator, was unable to form a government. Thwarted ultimately by the decision of the other new entrant in 2011, Gregor Virant’s Civic List, to join forces with Janez Janša’s centre-right Slovene Democratic Party, Mr Janša returned to the prime minister’s office he had held from 2004-2008.

Mr Janša’s government, however, did not survive the parliamentary term, due to a constructive vote of no-confidence in February 2013 linked to an anti-corruption watchdog’s revelations involving Mr Janša himself. Mr Janša was replaced as prime minister by Alenka Bratušek, who had become acting leader of Positive Slovenia after Mr Janković had stepped back from the leadership of his party the previous year due to the findings of the anti-corruption commission which had pointed the finger of suspicion in his direction.

Ms Bratušek’s new coalition government, however, survived for little more than a year. Just prior to the European Parliament (EP) elections this year, Ms Bratušek submitted her resignation (and thereby the resignation of her government) ushering in a period of uncertainty. Slovenia’s first female premier had been successfully challenged for the leadership of Positive Slovenia by none other than Mr Janković himself. His desire to take back the party leadership not only engendered a split in the party, but provoked the governing coalition to collapse as the smaller parties in the government refused to work alongside Positive Slovenia with the charismatic but controversial Mr Janković at the helm, thanks mainly to revelations by the same anti-corruption commission in January 2013 which had implicated Mr Janša.

The secrets of success: novelty and the rule of law

The winner of the July 2014 election, Miro Cerar, savoured victory just six weeks after founding his eponymously named party (Stranka Mira Cerarja: SMC). Although, as Allan Sikk has argued, ‘the appeal of newness’ has been a potent mobilising narrative in party politics in Central and Eastern Europe in recent years, Mr Cerar’s success is not just a product of his political novelty.

Indeed, the law professor was not an unknown figure a month-and-a-half before the poll. He was a respected expert particularly on constitutional matters (he had been involved in drafting the new Slovene constitution at the time of independence) and had been a regular guest on television offering expert commentary. As much of the international press coverage of the elections was keen to stress, Mr Cerar’s name had resonance. His father was a gold medal winning Olympic gymnast, but rather than any dexterity inherited from the master of the pommel horse, Mr Cerar junior’s appeal lay in his expert knowledge of the law.

Law and novelty were at the heart of his appeal. Not only did Mr Cerar claim a vote for his party would give a chance to new faces, but he also called for the re-establishment of the rule of law in Slovenia and a change in the country’s political culture, particularly for more co-operative and respectful conduct between political opponents. Mr Cerar’s appeal resonated with large sections of the Slovene electorate who had lost faith with their politicians and political system.

Protests and party politics

Slovenia has undergone a tumultuous few years. Not only has the country experienced tough austerity measures, the shenanigans of party politics (outlined above) and the controversial incarceration of a former prime minister (Mr Janša), but there were also widespread demonstrations. Initially sparked off by disputes over a ‘disproportionately large network of speed cameras’ around Slovenia’s second largest city Maribor, a series of demonstrations, dubbed the ‘Maribor Uprising’, took place over the winter of 2012-13 with some of these turning violent.

Some of the protestors formed the core of Solidarity which forged an electoral coalition with the Social Democrats (SD). Solidarity, however, contributed little to the Social Democrats’ electoral success. Indeed, the electoral coalition may rather have contributed to the biggest defeat in Social Democrats’ history with the party garnering just 5.9 per cent of the vote.

Another part of the protestors formed the Initiative for Democratic Socialism which became part of the United Left (ZL) coalition. The Initiative was seeking to change fundamental thinking in politics. Among its most radical proposals was the idea to cap the highest salaries at no more than five times higher than the lowest paid worker. In contrast to Solidarity’s impact on the Social Democrats, the Initiative and its young leader’s impact on the United Left was positive, probably contributing to its unexpected success in winning just under 6 per cent of the vote. Having said that, a year-and-a-half on from those huge demonstrations, it is fair to say that the Maribor Uprising – and a later, more general protest wave – did not translate into significant changes in party politics, thanks in no small part to the difficulty in organising political parties from a diverse movement.

Potent appeals: corruption and the rule of law

If there is one word which encapsulates what fuelled the fires of discontent shown in the Maribor demonstrations and acted as a motor of politics it is ‘corruption’. There was a widespread feeling in Slovenia that politics, politicians and indeed the entire system was bedevilled by corruption. Although few front-line politicians and parties were tarred by the brush of corruption, the focal point for many of the accusations and counter-accusations was Mr Janša.

The former prime minister was found guilty in 2013 of taking payments from a Finnish defence contractor during his 2004-2008 spell as Slovenia’s premier. In April 2014 the verdict was upheld by the Court of Appeal and Mr Janša was sent to prison. As we have written elsewhere, Mr Janša is a controversial figure akin to a Richard III style villain to his opponents, but to his party faithful he is a heroic leader like Henry V. The supporters of Mr Janša and his Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) saw the court’s verdict as politically motivated. The party’s poor showing in the election (20.7 per cent) provoked it to claim the elections were not free and fair – and, therefore, also not legitimate – the first time any Slovenian party had made such a claim in twenty years of independence.

European themes: secondary and largely absent

Central to the campaign was the debate over how the different parties would tackle the country’s economic difficulties. This theme was linked to EU politics, particularly the European Commission’s recommendations to Slovenia (together with deadlines to achieve them) to tackle the country’s debt and economic woes.

Prior to the election, the Commission had recommended the consolidation of public finances, further privatisation and a fight against corruption. Apart from this indirect impact, however, European issues and themes were notable for their absence in the national electoral campaign; perhaps no surprise given the EP elections in May, where we might have expected European issues to be more prominent, were also dominated by domestic themes.

More than just riding the wave

Winning an election for a new party riding on a wave of discontent with the existing menu of parties is not the hard part. The poetry of campaigning is now replaced by the prose of governing. Mr Cerar’s main initial task is to form a governing coalition. Thanks to the Slovenian Democratic Party’s stance on the elections and Mr Cerar’s moderate left-leaning economic agenda, the latter’s party looks certain to form a coalition with some of the smaller groupings on the left.

He has expressed a desire to form a broader-based coalition with the inclusion of the New Slovenia-Christian Democrats party, but the latter’s preference for neo-liberal economic policies makes a government combining forces of the left and right unlikely. Almost certainly the pensioners’ party (DeSUS), which has been part of most coalition governments in the past two decades, will be included in the coalition. Thanks to its more loyal, older voter base in an election with a lower than usual turnout (51 per cent), the pensioners won 10.2 per cent of the votes.

Slovenia faces tough economic choices, especially in dealing with its public debt. The country looked to be on the brink of needing a Eurozone bailout on several occasions in the past few years. Mr Cerar and his party of experts (and new faces) will need to deploy all their expertise to ensure the country does not fall into that trap.

The problem with appeals based on novelty is that they don’t remain new for long. Playing the anti-corruption and rule of law card is easy in an election campaign, but much harder in government. As Gregor Virant and Zoran Janković, whose parties entered both parliament and government after the 2011 elections, discovered, new parties can be difficult to manage and have less of a sense of cohesion once the tough challenges of governing begin.

Mr Cerar’s new cohort of parliamentarians was attracted by the party leader’s expertise, novelty, rule of law and anti-corruption appeal. His challenge is to convert that attraction into deeper-rooted attachments to ensure the party remains coherent and cohesive whilst taking the difficult, and probably unpopular, decisions needed to tackle Slovenia’s economic woes.

This article was cross-posted at the European Parties Elections and Referendums Network (EPERN) blog

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: Luigi Rosa (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1jDn2JS

_________________________________

Alenka Krašovec – University of Ljubljana

Alenka Krašovec – University of Ljubljana

Alenka Krašovec is Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science and Centre for Political Science Research, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana.

–

Tim Haughton – University of Birmingham

Tim Haughton – University of Birmingham

Tim Haughton is Reader (Associate Professor) in European Politics at the University of Birmingham and is currently writing a book on political parties in Central and Eastern Europe.