In April, the Spanish parliament rejected a request by Catalan authorities to hold a referendum on Catalonia’s independence from Spain, which had been proposed for November this year. Diego Muro and Martijn Vlaskamp argue that the Spanish government requires a more positive message for the people of Catalonia if it is to reduce public support for independence.

In April, the Spanish parliament rejected a request by Catalan authorities to hold a referendum on Catalonia’s independence from Spain, which had been proposed for November this year. Diego Muro and Martijn Vlaskamp argue that the Spanish government requires a more positive message for the people of Catalonia if it is to reduce public support for independence.

The Catalan secessionist movement may fail in bringing about the political independence of Catalonia, but it has already succeeded at one thing: getting their supporters’ hopes up. Within the pro-independence campaign there are many enthusiasts who willingly spend their free time collecting signatures, organising talks and attending rallies with the hope of realising a brighter political project for the future.

In contrast, the campaign in favour of the status quo is being carried out by the Spanish Government with the support of a handful of Catalan organisations and has been characterised by disdain, neglect and even intimidation. Unsurprisingly, the government’s negative campaign has failed to convince Catalans who want to go it alone.

Spaniards and Catalans against secessionism may have reasonable arguments but their discourse is too often limited to delivering criticism. Supporters of the status quo complain that secessionists are misleading Catalan citizens in presenting a rosy picture of the future. They grumble that the sustainability of new states is unclear and that the nationalists’ position over issues such as membership of NATO or the EU is little more than wishful thinking.

They also object that the harsh realities of the Great Recession have contributed to making political independence more attractive and that the real problem is economic, not political. If Spain was going back to providing high quality public goods for all its citizens, they hope, support for separatist dreams would fade away. These are all valid points, but ultimately the anti-secessionist campaign only delivers a negative message – why secession is a bad idea – while failing to offer arguments to the effect that staying together would be a better option.

One of the pillars of the Spanish Government’s campaign against Catalan secessionism is the international ostracism a Catalan state might face following independence. The Spanish Foreign Minister, José Manuel García Margallo, argued that an independent Catalonia would be ‘damned to wander outer space and would be excluded from the European Union for ever and ever’. The Interior Minister, Jorge Fernández Díaz, further claimed that political independence meant being outside ‘all EU treaties as well as NATO’ and that Catalonia would be a fertile soil for ‘international terrorism and organised crime’.

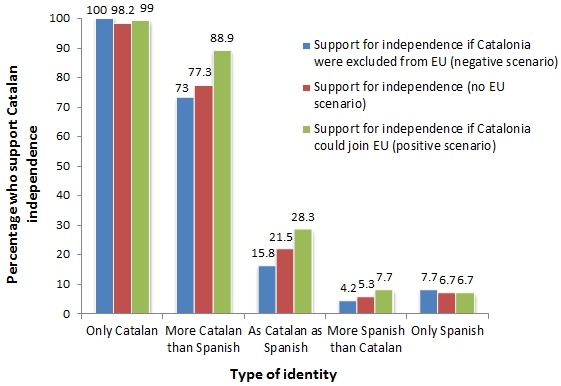

But such threats about international isolation will not be a game-changer. In a recent study funded by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, we confronted 1,200 Catalan voters with various scenarios regarding the EU membership of an independent Catalonia. Even when confronted with a scenario of ‘EU exclusion’ more than 55 per cent of Catalans opted for independence (without this treatment more than 60 per cent of Catalans voted for secession). The Spanish executive should be especially concerned about the fact that even among Catalans who feel both Spanish and Catalan, and who tend to be less nationalist, more than 70 per cent intended to vote in favour of independence under these circumstances. Amongst those whose identity was ‘only Catalan’ support for independence was almost 100 per cent.

Our findings seem to suggest that for many Catalans even the threat of EU exclusion is not credible or strong enough to substantially change their preferences. As can be seen in the Chart below, support for secessionism remains largely stable in all identity groups despite the ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ scenarios concerning EU membership. Those with single identities (‘only Catalan’, ‘only Spanish’) are less likely to change their preferences for secession than those with dual identities (‘more Catalan than Spanish’, ‘as Catalan as Spanish’, ‘more Spanish than Catalan’). The findings therefore confirm the idea that self-identification and support for secession are highly correlated and that threats are not very effective.

Chart: Percentage of people in Catalonia who support independence under ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ scenarios over EU membership (by identity group)

Note: The Chart separates respondents into groups based on their identity – from ‘only Catalan’ through to ‘only Spanish’. The percentages represent the respondents within each group who supported Catalan independence under three different cases – 1) when they were told Catalonia would not be able to join the EU, 2) when they did not have any direction on Catalonia’s future EU membership, and 3) when they were told Catalonia would be able to join the EU. Figures are from the authors’ study funded by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation.

The Spanish Government has not come up with an alternative strategy to counter the seemingly unstoppable rise of secessionist attitudes in Catalonia. Many of the grievances of ordinary Catalans are quite similar to those of otherSpaniards and they can be fixed, if there is political will. According to polls conducted by the Catalan Government, the ‘relationship with Spain’ is not even among the top problems of Catalan citizens (only 20 per cent of the respondents mentioned this issue and not more than 8 per cent of them ranked it first on their list of priorities). Catalans mostly care about unemployment, general economic problems and political corruption: issues that score just as highly in the rest of Spain.

The secessionist campaign in Catalonia has managed to create an appealing movement driven by positive messages about the real chance of ending these grievances ‘right here, right now’. The Spanish Government cannot counterbalance this democratic movement by disregarding popular demands, not engaging at all (PM Rajoy’s favourite strategy), or bullying Catalan voters with ineffective threats (as our research has suggested).

Instead, Madrid-based politicians need to come up with specific proposals about a Constitutional reform, a new funding system, protection of language rights, and improving health and education, among other areas, instead of barricading themselves behind the legal status quo. Either that or they will continue to throw more wood into the bonfire of secessionism.

But even if Spanish politicians are quick to react, it is doubtful that the ardent desire to secede can be calmed down at this stage anymore. By not engaging in a constructive way with the problems, the Spanish Government has enabled secessionists to create such a momentum that most Catalans now want to express their frustration in voting, whether in a referendum on November 9th or in snap elections.

Will Madrid be able to offer a positive political project capable of keeping the country united? Calls for profound reforms and changes are not unique to Catalonia, but are also voiced in the rest of Spain. Spaniards mistrust key political institutions (governments, parliaments and political parties) and there are signs of exhaustion with respect to the current political system, as indicated by the emergence of new parties, increasing social mobilisation, and unprecedented rates of political disaffection.

Recently there was misplaced hope that the new King Felipe VI would be able to initiate a ‘second transition’, similar to the one his father contributed to when Spain was transitioning to democracy in the 1970s, but the monarch’s powers are largely ceremonial. In the end, politicians and representatives will ultimately be responsible for coming up with specific proposals to regenerate Spanish politics and accommodate Catalan aspirations. If these proposals are crafted in a positive manner, they may convince more Catalans than the current negative campaign of indifference, contempt, and intimidation.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: Olli A (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1qyY9SM

_________________________________

Diego Muro – Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI)

Diego Muro – Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI)

Diego Muro is Assistant Professor in Comparative Politics at the Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI). Prior to joining IBEI he was Associate Professor in European Studies at King’s College London and Senior Fellow at St Antony’s College, University of Oxford.

Martijn Vlaskamp – Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI)

Martijn Vlaskamp – Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI)

Martijn Vlaskamp is a doctoral researcher at the Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI) and a PhD candidate at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. His research interests include EU Foreign Policy; natural resources and armed conflicts; and illicit trade.

This is quite a different picture to Scotland, where a significant proportion of those with a strong Scottish identity still oppose independence. You certainly wouldn’t get 100% of Scots with an “only Scottish” identity backing independence. Identity does play a role there, but it’s not as clear cut as the chart here and the argument is driven more by practical issues.

In other words we don’t have a situation where having an exclusively Scottish identity is inconsistent with wanting to stay in the UK – yet the chart in this article would imply that’s precisely the situation you have in Catalonia. The question would be why opinion has become so extreme in that sense and whether it’s just ingrained in the electorate or is a reflection of how the Spanish government has responded (clearly the main difference in Scotland is that the UK allowed the referendum to take place).

Alan Merton, another significant difference is that, unlike Scotland, Catalonia has never consented to be part of a kingdom that rules it “by right of conquest.” There have been many periods when the majority of Catalans (historically gifted with a talent for “pacts”) cooperated with a triumphant Madrid, pursuing hopes of modernizing and democratizing Spain, but those hopes have been repeatedly, and now definitively, dashed. Hence the results reported above (which even underplay the massive role that cultural factors, even more than economic ones, play).

Good article, though you shall also take into account the political consequences of the fact that Spanish government does not allow the referendum in Catalonia (explained by you in the article’s introduction), thereby giving a sort of moral legitimacy to Catalan independence supporters. Just to add some figures, while as you argue around 55 % of Catalans may vote in favour of independence, a greater majority of around 75 % supports holding a referendum.

I mean, in recent months, besides constant menaces on the consequences of hypothetical Catalan independence by Spanish government, it has been really easy to defend independence in Catalonia using the “democratic argument”. Pro-independence political parties and associations are able now to make a sort of relation between the concepts “independence” and “democracy” (“Volem votar”, “We want to vote”), thanks to the Spanish government’s continuous denial to hold a referendum. Living in Catalonia, it’s a long time without hearing economic arguments in favour of independence, the favourite one now is the “it is just about democracy”, which gives to pro-independence side a huge advantage.

If you allow me to criticize a point in your article …

Your questions groupping people if they feel more ‘Catalan’ or ‘Spanish’ propably has been done because yhis question has been traditionally used in polls in Catalonia.

For who do not knows catan or spanish politics let me explain why this questions is tendencious and has been used traditionally for who want an unitary Spain:

– A large part of catalans are of mixed origins : catalan, spanish or elsewhere.

– Therefore while many population can feel themselves 100% politically catalan witth this question you are forcing them to answer they are a mix of catalan-spanish – because its ancestors are in fact are -. But one think is ethnicity and others politics.

– On the other part some people who are fully Spanish can answer as well a mix results. Because they feel ‘regionally catalan’, while in fact they can negate Catalonia is a nation, or have its own culture.and only recognize Catalonia to be a spanish region how it can be La Rioja or Extremadura.

At the end, while you could be arrived to correct interpretation, your data is biased by a bad.question.

P.S.: Let me explain in plain words: For a lot of Catalan poppulation, you are asking if they love more his father or her mother, so you can always get a result of ‘one of them, but the other too’ and not how they are politically identified.

I think the bottom line here is that more and more “pact-prone” catalans have finally reached the conclusion that the only dignified response towards spanish disregard and violent undertones is independence. The cycle of repression (political and otherwise) by which Spain has always controlled catalan nationalistic outbursts is no longer viable in a western EU context. Threat and use of force from an overwhelming enemy hasn’t stopped catalans in the past. Just kept them subdued. What could stop them now?

Catalans have been in a distance run towards independence for centuries -the only thing unclear now is how close they are to the finish line.

I bet you a hair that major Spanish newspapers and television channels simply will ignore this analysis

I was born in Barcelona, to immigrant parents from other regions of Spain. I have lived in other regions of Spain and have traveled all over the country, and half of Europe, Canada, USA and many Latin American countries. My perspective is critical and I value all opinions to form my own idea. My appologies for my English.

The article accurately reflects in their conclusions the Catalan sentiment towards independence and the questions are correct. In my opinion, need explain in more detail the indignation of Catalonia by the campaign against the Catalan products and Catalan Statute (voted for the Catalan people) that the actual Goverment (PP, Popular Party), started during the years when he was in opposition. This was the actual seed that started the majority accession to independence. The policies implemented since it governs the PP and especially against language and education in Catalan, have continued adding followers. Their indifference and opposition to a referendum requested by 75% of the Catalan population, despite its origins, has done the rest.

Whatever the outcome in the future will be studied in the faculties of Political Science and Master in the orientation of the diplomatic staff “The process of Catalan independence: 298 years of waiting and a incompetent management, that accelerated the process in only 2 years.”

The answer was very easy. The same It gave Canada to Québec. We love you. We do not want you leave. What can we do for you?

This analysis is asking for a Third Way, between statu quo and Independence. And this way does not exist. The Solanistan experiment that was implemented in Serbia-Montenegro to avoid the Independence of Montenegro was a failure.

The very fact is that Spaniards do not consider Catalonia as a nation, that is, as a political subject. They consider Catalonia only as an Autonomous Community, a subordinate body to Spanish Central Powers. They reduce all to debate to a territorial-administrative-legal management affair.

On the contrary, a growing number of Catalans, see themselves as a nation, a people in the sense of the United Nations definition, and act politically accordingly. They are fed up with the supremacist policies from Madrid in areas such as language, fiscal affairs, business, infrastructures, and so on, and think that the right moment is arrived for Independence.

The PP-PSOE alternative means a progressive minorisation of the Catalan identity and prosperity, doomed to become a region of low skilled workers in tourism, as a monoactivity, in the same way as the Catalan identity has become in France: a folkloric, patois expression for tourists.

New political parties, such UPyD, are even worst, since favours the suppression of Catalan Autonomy. In the case of the new kid in the block, that is, ¨Podemos¨, it is not good news the fact that its popularity comes from a TV channel that belongs to a multimedia group totally opposed to Catalonia´s right to decide.

To conclude, Catalans are committed to vote, and Spain rulers and politicians and media outlets do not want this to happen. The key element, in this scenario, is that Catalans will keep its word until the end, and if the case arrive, if Spanish Government will send its Guardia Civil and Police units to confiscate thousands of two euros worth polling boxes spread in the territory. That, for sure, will be a good present for photojournalists, audiovisual agencies, and also for twitters, instagramers users.