Recep Tayyip Erdoğan won Turkey’s presidential election on 10 August, becoming the first directly elected President in the country’s history. Firat Cengiz writes that while Erdoğan’s ultimate aim is to establish a presidential system in Turkey, his strategy rests on securing an increase in support for his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) at the 2015 parliamentary elections. She notes that this could prove difficult because Erdoğan, as a formally neutral President, will no longer be able to lead the AKP in the election.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan won Turkey’s presidential election on 10 August, becoming the first directly elected President in the country’s history. Firat Cengiz writes that while Erdoğan’s ultimate aim is to establish a presidential system in Turkey, his strategy rests on securing an increase in support for his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) at the 2015 parliamentary elections. She notes that this could prove difficult because Erdoğan, as a formally neutral President, will no longer be able to lead the AKP in the election.

On 11 August 2014 Turkey’s freshly elected 12th President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gave his fourth ‘balcony speech’ from the headquarters of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Ankara. Erdoğan’s speeches have now become a post-election victory phenomenon in which the AKP leader attempts to reassure Turkey’s increasingly marginalised opposition. Accordingly, in his fourth speech Erdoğan called on all of Turkey’s political groups to kick-start a ‘social reconciliation process’.

Turkey’s increasingly polarised society has long needed such a process that is even more imminent in the shadow of increasing security threats facing the region’s minorities. An economically and politically strong Turkey in which a diversity of religious, cultural and ethnic groups peacefully co-exist would also provide security to those living beyond its borders. As recent catastrophes have shown, Yezidis and Kurds of the region, who have suffered from the tyranny and violence of different political and religious groups throughout history, are particularly in need of such security.

Nevertheless, Erdoğan’s past track record of keeping his promises does not bode well for the future of such a ‘reconciliation process’: the peace process with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) has all but failed for the second time. Turkey’s marginalised opposition have faced extreme police brutality since the Gezi Park protests in the summer of 2013 as well as at its first anniversary. Demands for equality for all minorities, including the Kurds, Alaouites, women, LGBT and other cultural and religious minorities have been completely ignored in the context of the recent constitutional reform process. The Soma mine disaster that claimed the lives of more than 300 miners has not instigated a serious attempt to improve the increasingly dire conditions facing Turkey’s working class.

Erdoğan’s lack of credibility to start and manage a social reconciliation process is particularly disappointing, since he is – as the country’s first directly elected president – more likely to succeed in such a process than before. Turkey’s Constitution had foreseen the country’s president to be elected by Parliament, as is usual in parliamentary democracies. Nevertheless, non-majoritarian institutions, including the military and the Constitutional Court, interfered with the election process of Turkey’s 11th President Abdullah Gül. In response, in a tactical move the Parliament amended the Constitution to establish direct public elections starting from the election of the 12th president.

Erdoğan has long desired to be Turkey’s first publicly elected president. The result of the 10 August elections has not come as a surprise: Erdoğan won the elections in the first round by securing just under 51.8 per cent of the vote against Eklemeddin Ihsanoğlu, the candidate of the central left-right coalition, and Selahattin Demirtaş, the candidate of the Kurdish People’s Democratic Party, who received around 30.4 per cent and 9.8 per cent of the vote respectively. The pre-election campaign process was extremely unexciting and uninspiring: this was partially due to Erdoğan’s almost guaranteed victory and partially due to the central left-right coalition’s failure to identify a dynamic reformist candidate.

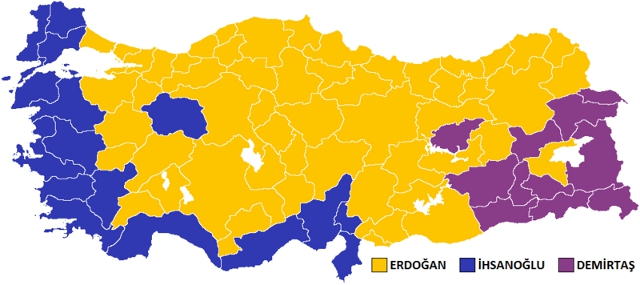

The result of the presidential elections are almost an identical repetition of those of the 2011 general elections and the 2014 local elections: as shown in the Figure below, Demirtaş received the majority of votes in the Kurdish region as well as the marginal votes in the metropolitan areas with an election campaign that spoke not only to Kurds but to all marginalised groups including women, LGBT, working classes and other minorities. Ihsanoğlu received the majority of votes in the country’s Aegean and Mediterranean cost-line. Erdoğan secured the majority of votes in all other regions. In summary, the public did not perceive the country’s first presidential elections any differently than the parliamentary and local elections.

Figure: Candidates which received the majority of votes in Turkish regions in the 2014 presidential election

Note: Figure compiled by Maurice Flesier based on the unofficial results of 11 August. Reproduced for illustrative purposes under a creative commons licence (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

At first glance Erdoğan may seem to have entrenched his political power even more strongly after achieving this new and long desired post. Nevertheless, his and his party’s near political future might turn out to be unexpectedly tricky. Turkey’s Constitution still foresees an institutional regime based on the dynamics of a parliamentary democracy. Thus, the President enjoys only symbolic powers and is expected to be officially politically neutral, although practically the latter has seldom been the case so far.

Naturally, Erdoğan is not content with the miniscule powers currently invested in the presidency. Thus, in the current constitutional reform process that was launched after the 2011 parliamentary elections Erdoğan and his party’s primary aim has been to replace Turkey’s parliamentary democracy with a semi-presidential regime. Nevertheless, AKP, despite its absolute majority in Parliament, still does not enjoy the supermajority necessary to amend the Constitution singlehandedly. Thus, Erdoğan would like to see the AKP increase its vote in the forthcoming 2015 parliamentary elections.

However, Erdoğan will not be able to lead the AKP in the next parliamentary elections, as he must resign from his position of the party leader, due to the politically neutral position of the President. He openly declared that he wishes to see a powerful figure take over the party leadership and this is vital if the AKP is to preserve, let alone extend, its parliamentary majority. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen if Erdoğan will be able to work closely with and accommodate another powerful political figure.

Additionally, his resignation might result in a political fragmentation in the AKP: the previous President Abdullah Gül implied that he is up for the task, but it is known that Erdoğan favours the current Foreign Affairs Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu. Neither potential candidate comes close to Erdoğan in terms of their charisma and the support they enjoy within AKP. Political life is very unpredictable – particularly so in Turkey, and an unlikely party leader might also emerge in the near future. Nevertheless, if the AKP’s electoral popularity suffers from the change in leadership, Erdoğan might be locked in a marginalised powerless post for the foreseeable future. Thus, his insistence on becoming the first directly elected President of Turkey might turn out to be a politically premature move.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1uWk4Ex

_________________________________

Firat Cengiz – University of Liverpool

Firat Cengiz – University of Liverpool

Firat Cengiz is lecturer in law and Marie Curie fellow at the University of Liverpool. Her primary research interests are in Europeanisation and multi-level governance. She is the author of Antitrust Federalism in the EU and the US (Routledge, 2012) and the co-editor of Turkey and the European Union: Facing New Challenges and Opportunities (with Lars Hoffmann, Routledge, 2014).