Public opinion on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) rights has undergone a significant shift in Europe in recent decades; however there is still substantial variation in terms of the way in which legal systems within EU states deal with the issue. Zselyke Csaky writes on LGBT rights in the member states which have joined the EU since 2004. She argues that with some of the new member states still falling short of the standards in Western Europe, the EU should do more to encourage reforms.

Public opinion on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) rights has undergone a significant shift in Europe in recent decades; however there is still substantial variation in terms of the way in which legal systems within EU states deal with the issue. Zselyke Csaky writes on LGBT rights in the member states which have joined the EU since 2004. She argues that with some of the new member states still falling short of the standards in Western Europe, the EU should do more to encourage reforms.

Ana, an LGBT activist in Croatia, was jubilant when her government adopted a law recognising same-sex partnerships in July. By then, the country’s centre-left government had been discussing legal recognition for almost two years. She and her friends were less happy last December, however, when Croatians decided to outlaw gay marriage in a scantly attended referendum. “I think we still have a long way to go,” she said, “but we are optimistic that EU accession will speed things up.”

Not everyone is so convinced that the emerging European trend – of expanding rights for LGBT people based on the case law of the European Court of Human Rights – will trickle down to new EU member states. Some think that differences between old member states and countries that joined after 2004, often referred to as the “East/West divide” on LGBT rights, are here to stay. They argue that the EU lacks specific mechanisms to enforce human rights norms, let alone bring about reforms, once a country joins, and that new member states will continue to lag behind in providing the full spectrum of human rights to LGBT people.

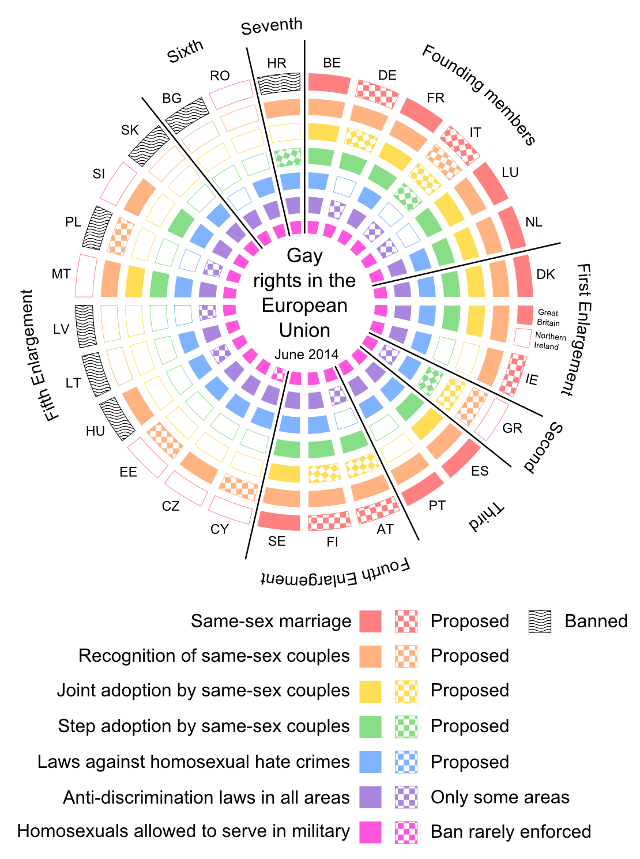

Public opinion has changed considerably in the past decade, but gay marriage is still much more widely accepted in Western European countries than elsewhere in Europe. Indeed, while several Western European countries have legalised same-sex marriage in the past few years, bringing the number of EU member states with marriage equality to nine, the opposite seems to be taking place in Central Europe and among candidate countries. Slovakia and Macedonia recently followed in Croatia’s footsteps and approved amendments to their constitutions that define marriage as a union “between a man and a woman.” Currently, seven EU members and three candidate countries have constitutional bans on same-sex marriage, with just two of them, Croatia and Hungary, keeping civil unions open to gay people. Figure 1 below shows the level of LGBT rights in each of the EU’s 28 member states.

Figure 1: LGBT rights in EU member states

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It is true that there have been significant advances in codifying legal protections against discrimination and harassment of LGBT people in Central Europe and the Balkans. In addition to Croatia and Hungary, two other countries in the region – the Czech Republic and Slovenia – allow civil unions that offer legal recognition to same-sex couples. Discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation is generally prohibited, and gay rights activists are free to speak their minds publicly. Pride parades are held every year in many countries, and although they are not free from minor incidents and sizeable counter-protests, more and more people join the marches. Around 10,000 people participated in the Budapest Pride event held in early July.

Yet discrimination persists in practice. For LGBT people in the Baltics, for example, it is an everyday reality. Although the Estonian parliament is currently debating a law on civil unions, only 34 per cent of the respondents to a recent opinion poll supported the idea, and the Foundation for the Protection of Family and Tradition collected 40,000 signatures against the initiative last year.

Similar conservative movements have sprung up in neighbouring Latvia and Lithuania. In November 2013, the Latvian nongovernmental organisation Protect Our Children started collecting signatures for a referendum on a Russian-inspired law that would ban the “popularisation and advertisement of sexual and marriage relations between persons of the same sex” in educational institutions or at events where children could be “participants or spectators.” Lithuania’s Law on the Protection of Minors has been on the books since 2010, banning the dissemination of public information that “expresses contempt for family values” or encourages same-sex relationships. Last spring, a children’s book promoting tolerance and acceptance of minorities was banned under the law, while an amendment currently pending in the parliament would penalise “denigrating” family values in public – including in speeches, slogans, and audiovisual materials – and prescribe up to around 1,850 euros in fines for repeat offenders.

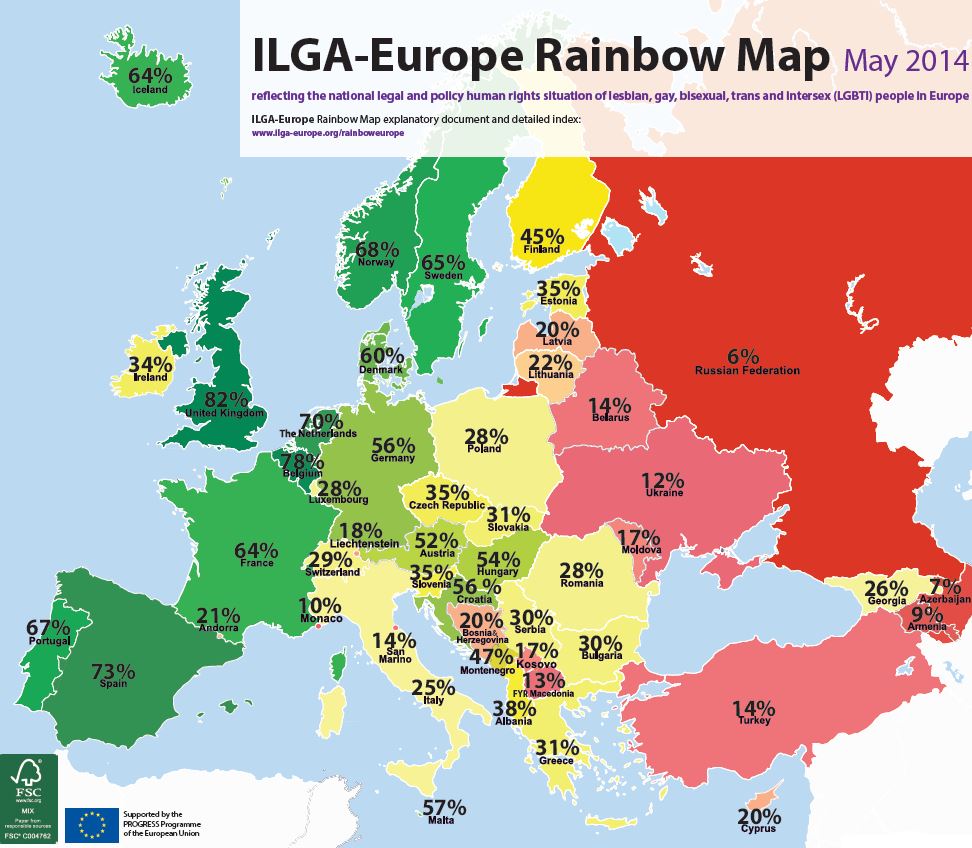

In the Balkans, pride events are a less common occurrence, and Freedom House’s annual Nations in Transit report has found considerable resistance to attempts to harmonise LGBT-related legislation with European standards. This year’s Belgrade pride march, which had been banned due to security concerns since 2010, was postponed until late September due to extensive floods in the country in May. Authorities also postponed the march in Montenegro, after the first Podgorica pride event was marred by violent clashes last year. Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo have never hosted a pride march, and violence against LGBT people and communities is prevalent in both countries. In February, for example, assailants attacked members of a panel on transgender issues at the Merlinka film festival in Sarajevo. An overall representation of LGBT rights in Europe is shown in Figure 2 below, where a rating of 0 per cent indicates the lowest level of rights, while 100 per cent represents the highest level.

Figure 2: LGBT rights ‘scores’ in European countries (click to enlarge)

Note: Based on the ILGA Europe scoring system where 0 per cent indicates the lowest score for LGBT rights and 100 per cent the highest score. For a full explanation see here.

Explaining the decline in LGBT rights

So what is behind the apparent pushback on human rights for LGBT people, including the recent constitutional amendments in Hungary (2012), Croatia (2013), Macedonia (2014), and Slovakia (2014), and the popular initiatives aimed at banning “gay propaganda” in Latvia and Lithuania?

Some might argue that Europe is experiencing a “spillover” of homophobic policies from Russia. While the initiatives in the Baltics are reminiscent of Russia’s recently adopted “gay propaganda” law, Lithuania’s ban has been in place for years. And although Russian legislation has certainly inspired some of the extremist parties in the region (see the replica of Russia’s “foreign agent” law put forward by Hungary’s far-right Jobbik party), the Kremlin’s influence is more obvious in Eurasia. In Kyrgyzstan, a harsher version of the “gay propaganda” law is currently pending in the parliament.

A somewhat more plausible explanation emphasises the conservative-religious component in many of the region’s countries. Religion definitely plays a role in Poland’s constitutional ban on gay marriage, which has been in effect since 1997 and is strongly supported by the Roman Catholic Church. Support from the church was essential to the success of Croatia’s referendum as well, with Catholic bishops urging Croatians to vote “yes” to the amendment outlawing gay marriage. In Romania, an Orthodox priest running on an antigay platform collected the 100,000 signatures necessary to stand as an independent candidate in the European Parliament elections in May. And Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has been forging a conservative image for a country that had previously been the first in the region to allow the registration of same-sex partnerships, in 2007.

Still, initiatives packaged in antigay rhetoric owe much of their prominence to the economic hardship experienced by many of the region’s citizens. Symbolic matters often come to the fore when populist politicians need scapegoats, and emotionally charged topics, such as the rights of LGBT people, can be used to distract attention from official mismanagement and difficult structural reforms.

In any case, it would be a mistake to conclude from these developments that EU reform pressure is counterproductive and simply provokes a traditionalist backlash. European influence has been shown to strengthen rights advocacy in the long run. Voters in Poland, for example, elected the country’s first openly gay and Europe’s first openly transgender members of parliament in 2011. Since legislation related to family matters is currently relegated to the domestic sphere in the EU, the bloc should make it clear that discrimination based on these laws will not be tolerated in either current or aspiring member states. Public opinion on LGBT issues might be rapidly changing, but populist urges can be hard to resist.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Zsolt Bobis and Marija Vareikaite contributed to this blog post. Featured image credit: Peter Gyöngy (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1uDmbvx

_________________________________

Zselyke Csaky

Zselyke Csaky

Zselyke Csaky is a Research Analyst at Freedom House.

Hi

I’m afraid the map is inaccurate. The United Kingdom is not a monolithic entity as regards human rights. In Northern Ireland the main political party, which is explicitly strict (some would say fundamentalist) Christian, has refused to extend LGBT and other rights they perceive as being “immoral” or “unnatural” to UK citizens there. I’d put them down there with Latvia.