The Spanish and Catalan governments have been engaged in a dispute over a proposal to hold a referendum on Catalonia’s independence from Spain on 9 November. Luis Moreno writes on the social attitudes underpinning the debate in Catalonia. He notes that against the backdrop of the financial crisis and the opposition of the central Spanish authorities to holding a referendum, the percentage of Catalans expressing an exclusive Catalan identity has risen significantly in recent years.

The Spanish and Catalan governments have been engaged in a dispute over a proposal to hold a referendum on Catalonia’s independence from Spain on 9 November. Luis Moreno writes on the social attitudes underpinning the debate in Catalonia. He notes that against the backdrop of the financial crisis and the opposition of the central Spanish authorities to holding a referendum, the percentage of Catalans expressing an exclusive Catalan identity has risen significantly in recent years.

Catalan authorities (parliament, government, local councils) have promoted the “official” celebration of a consultation on independence for 9 November. However this proposal was changed significantly on 14 October and the referendum will not take place in its original form, in compliance with a resolution by the Spanish Constitutional Court putting a halt to the popular consultation. The highest tribunal and interpreter of Spain’s constitutional order had ruled that the referendum does not comply with the provisions of the 1978 Constitution and related legislation.

Very much against the expectations created in the old Catalan Principality, a referendum like the one held in Scotland on 18 September will therefore not occur. In the event that the Catalan government of the Generalitat, and the local councils, went ahead with its original decision, the referendum outcome would generate notable uncertainty. An act of civil disobedience by refusing to comply with the decision of the Constitutional Court would most probably meet with the reaction of Spain’s rule of law, perhaps by means of suspending certain activities of Catalonia’s government. If the consultation is carried out “unofficially”, it would have no formal consequences, but would certainly feed into the on-going discussion about the possible secession of Catalonia from the rest of Spain.

Social attitudes and Catalan independence

The social attitudes underpinning Catalonia’s referendum conundrum swing between the ancestral Catalans’ seny (common sense) and rauxa (outburst). If the former implies sensibleness and a well-reasoned perception of situations, the latter compels the adoption of direct action when it is felt that no other course of action is more effective. In other areas of Spain, the popular term justicia catalana refers to the untangling of situations of perceived unfairness by the recourse to personal agency and, ultimately, force.

Within the present context of centre-periphery confrontation, it would be misleading not to mention the recurrent adoption in contemporary times of the centralist so-called trágala (swallow it) practices. These were often imposed by weak – and generally despotic – Spanish governments upon the aspirations channelled by Catalan elites to be a community on its own, politically differentiated from the rest of Spain.

The historical background here is that following the civilWar of the Spanish Succession and the surrender in Catalonia of the Archduke Charles of Austria s troops on September 11, 1714, to those of the Bourbon Philip V, the Principality’s self-governing institutions and its political rights which originated in medieval times were cancelled. Unlike the process of decline experienced by Spain during the 19th and 20th centuries, the Principat de Catalunya witnessed both unprecedented cultural revival and economic growth. Very much like the symbolic date of 1314 (Bannockburn) for the Scots, 1714 has been made to represent a historical yardstick for Catalan contemporary nationalists. They have pressed to “regain” Catalonia’s independence three hundred years later. As in Scotland, the Catalan case underlines the political salience that symbolism and the recreation of history have for present-day social mobilisation.

A further attitudinal element which helps to explain the proportions and intensity of the late quest for independence concerns the so-called “demonstration effect”. After the massive popular demonstrations in the streets of Barcelona on the Diada (National Day – 11 September) in recent years, large sections of the Catalan population have internalised the prospect of having their own state on equal terms as, say, France, Norway or Spain itself. The popular drive behind such an aspiration was greatly fuelled by the repercussions of the 2008 economic crisis, which provided secessionist advocates with a “window of opportunity” to make the argument that Espanya ens roba (Spain robs us).

The allegation that with independence the Catalans would be richer than “lazy and thieving” Spaniards was reiterated constantly. The final assumption was based upon a conviction that the goal of independence was attainable, depending only upon the people’s will and determination. Such a popular will must also be influenced by the latest developments concerning the public confession made by Jordi Pujol, President of the Generalitat during 1980-2003 and father figure of contemporary Catalan nationalism, that he had been hiding money and assets abroad from Spain’s tax authorities.

Catalan independence campaigners have deployed an effective strategy of mobilisation by which the in-group (Catalonia) is kept highly motivated in its dispute with the out-group (Spain). All is aimed at maintaining the self-affirmative popular compulsion of ‘Yes, we can’ for the achievement of independence. Such an approach is in line with the ‘effects’ theorised by Thorstein Veblen as the best means to overcome unsuccessful attempts in the past, which can be turned into successful achievements in the future. According to such an understanding, the defeat in 1714 by the Bourbon pretender in the War of Succession can be turned into a victory if Catalans choose to do so. The belief is that pragmatism can make people, using their agency, shape the institutions of society according to the wishes.

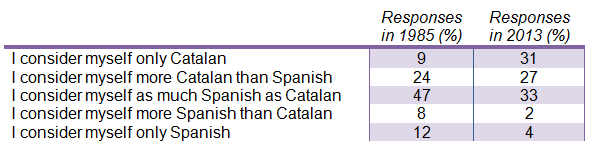

Unlike the Scots, over recent decades citizens in Catalonia have expressed a high degree of duality when identifying themselves. In 1986, a survey carried out in Scotland addressing for the first time what later has been coined as ‘The Moreno Question’, found that 39 per cent of the surveyed people considered themselves to be ‘Only Scottish’ without any identity sharing with Britain. After all these years, the percentage of ‘exclusivity’ in Scotland has remained rather stable with a slight increase in recent times. As shown in the Table below, in 1985, around 9 per cent of the people in Catalonia stated their ‘exclusive identity’. The assumption behind the formulation of ‘The Moreno Question’ was that when citizens in stateless nations such as Catalonia or Scotland identify themselves in an exclusive manner (“Only Catalan”; “Only Scottish”), the institutional outcome of this form of singular identification would also be exclusive. Demands for self-government would evolve towards claims of a right for independence and secession.

Table: Responses in Catalonia to the question: “In which of these five categories do you include yourself?” (1985 and 2013)

Note: Figures have been rounded to nearest full percentage. In 2013 there were 2 per cent of don’t know/refused responses. Figures from the two surveys are provided together for illustrative purposes only. Sources: Moreno, Luis (1986), PhD thesis, Decentralisation in Britain and Spain: The cases of Scotland and Catalonia, p. 68 (1985); and Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió (2013).

In the midst of the economic crisis and after the ruling of the Spanish Constitutional Court in 2010 – which was interpreted as a setback for Catalonia’s home rule aspirations – the percentage of those considering themselves as ‘Only Catalan’ rose significantly. According to the Barometer carried out in November 2013 by Generalitat´s Centre of Opinion Studies, 31 per cent of Catalans felt “Only Catalan”, more than three times the percentage recorded in the mid-1980s. It can be easily deduced from these figures that the increase in Catalans’ exclusive self-identification has been mainly contingent on circumstances and has grown rapidly in recent times. Greater numbers of Catalans have internalised the refusal of the Spanish central elites and, in particular, the rejection by the central Conservative Rajoy Government in 2012 to negotiate new financial arrangements, as an unacceptable development.

The need for a political agreement between the Spanish and Catalan governments

All things considered, the major dissimilarity between the Catalan and Scottish cases concerns the disparity in the formulation and organisation of their respective referendums. Alex Salmond and David Cameron, on behalf of both the Scottish Executive and British Government, signed “The Edinburgh Agreement’ on 15 October, 2012, which granted constitutional legitimacy to the referendum later held on 18 September, 2014. No such agreement has existed regarding both Catalan and Spanish governments, and the Generalitat opted to organise unilaterally the public consultation claiming that the Catalan citizenship had the democratic right to decide according to the following wording and sequence of questions: “(a) Do you want Catalonia to become a State? (Yes/No); If the answer is in the affirmative: (b) Do you want this State to be independent? (Yes/No). You can only answer the question under Letter (b) in the event of having answered “Yes” to the question under Letter (a)”.

It is nonsense to impede or curtail self-government in stateless nations such as Catalonia and Scotland in a political union like the EU. The EU proclaims territorial subsidiarity as the guiding principle for policy-making by establishing that decisions are to be taken supranationally only if the state, substate and local layers of government are not better equipped to implement them. Likewise, it would be misguided not to observe punctiliously the European tenet for democratic accountability, which applies to the legitimacy of all multi-governance institutions based on the rule of law. Political discussion, negotiation and eventual agreement are thus necessary and sufficient conditions. The alternative is anomie and dissolution.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/ZAkmnb

_________________________________

Luis Moreno – Instituto de Políticas y Bienes públicos (CSIC)

Luis Moreno – Instituto de Políticas y Bienes públicos (CSIC)

Luis Moreno is Research Professor at the Institute of Public Goods and Policies (IPP) within the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC). In 1986, he was awarded his PhD by the University of Edinburgh with the thesis, Decentralisation in Britain and Spain the cases of Scotland and Catalonia. His books include: The Territorial Politics of Welfare (Routledge, 2009), Diversity and Unity in Federal Systems (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010),Nationalism and Democracy (Routledge, 2010), and Europa sin Estados (Catarata, 2014).

Thank you for artcile, but I would like to make comments about some assertions you write in it but I think they are incorrect:

1.- ‘Spain robs us’ This is a topic used to define catalans in Madrid media, a lot more than can be listened in Barcelona

2.- ‘The allegation that with independence the Catalans would be richer than “lazy and thieving” Spaniards was reiterated constantly’. Another topic widespread from Madrid media, while very minoritary in Barcelona related to independence.

Also you miss some points, I judge importants as well,

1.- A referendum is allowed by Art 92 (Constitution) or a consultation by Art 123 (Statute). Obstinacy to forbid it showns to a growing number of catalan people an authoritarian bias to Spain politics.

2.- A growing number of catalans does not recognize legitimacy to Spanish Constitutional Court. They see it a politized, non-independent .court. This important, because in a democratic country a lack of legitimacy could invalidate decissions taken by this court.

3.- Spain goverment himself flouts a dozen of Constitutional Court sentences again him (some 20 years old). A very bad examplary when you want to enforce catalan people comply other sentences. This behaviour showns more a more to catalan people as arbitrary what Spain govt. decides about this ‘consultation’.

4.- What repetive mistaken has been made by Spanish ruling class to make catalans less and less identified with Spain ?

Thanks for your time

‘Spanish Constitutional Court having ruled that any such vote would be illegal’ this assertion is incorrect.

It is suspended. This happens automatically every time Spanish govt. sends to the court anything.

It is part of Spanish Constitutional Court disfunctionality. Becuase when it is send by other parts against Spanish govt, this does not apply.