What impact does political violence have on attitudes toward peace negotiations in conflicts such as those in Ukraine or Israel-Palestine? Daphna Canetti, Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler and Stevan Hobfoll present findings from a survey of Israelis and Palestinians on the effect of political violence on their attitudes toward peace. They find that contrary to the notion that force helps promote political solutions, individuals with greater exposure to political violence tend to exhibit more militant attitudes toward reaching a compromise in peace negotiations.

What impact does political violence have on attitudes toward peace negotiations in conflicts such as those in Ukraine or Israel-Palestine? Daphna Canetti, Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler and Stevan Hobfoll present findings from a survey of Israelis and Palestinians on the effect of political violence on their attitudes toward peace. They find that contrary to the notion that force helps promote political solutions, individuals with greater exposure to political violence tend to exhibit more militant attitudes toward reaching a compromise in peace negotiations.

Ending longstanding conflicts is a first-order global goal, with dozens of countries having been affected by ongoing armed civil conflict over the past decade. Given the growing proportion of civilian victims in political conflicts, there has been a concomitant increase in the number of people exposed to stressful events associated with political conflict.

The question of how and to what extent individual-level exposure to political violence impacts civilians’ willingness to compromise for peace thus demands attention. The relationship between terrorism and political violence on the one hand, and political outcomes on the other, has long presented an alluring puzzle. Civilian attitudes to war and peace should be understood as pivoting on their personal exposure to violence and related stress reactions.

In a recent study, we analyse 1,627 individuals from 149 communities across Israel and Palestine (East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza) to investigate this problem. Contrary to the view often promulgated by both state and non-state actors – namely, that force promotes political solutions – we provide evidence that exposure to political violence reduces willingness to compromise.

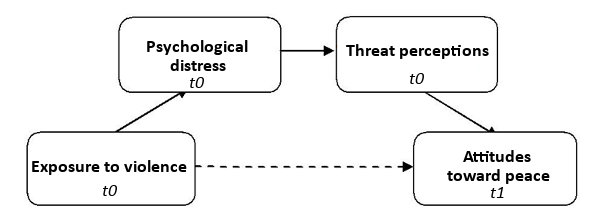

We propose a mediation model such that individuals exposed to political violence will be less willing to compromise for peace to the extent that they experience psychological distress and threat perceptions. Our analysis reveals that under prolonged exposure to political violence, elevated levels of distress influence perceptions of threat, which in turn are associated with more intransigent and militant attitudes. The Figure below presents an illustration of this model between 2007 (indicated as t0) and 2008 (t1).

Figure: Hypothesised model explaining changes in attitudes towards peace as a result of exposure to ongoing conflict

Note: The research is based on two surveys of respondents with the second survey taking place six months after the first (to assess how attitudes had changed). The first surveys were carried out in 2007, with the follow up surveys taking place in 2008. In the figure above, the year 2007 is indicated by “t0” with 2008 shown as “t1” to illustrate the time lag between the initial exposure to violence and changes in attitudes toward peace.

Marked by a large power imbalance and the existence of structured inequalities, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is one of the deepest and most prolonged conflicts in modern history. Even in times of relative peace, the daily stress of enduring occupation for the Palestinians, or maintaining vigilance against terrorist attacks or rocket fire for Israelis, takes its toll on the mental, cognitive, and physical functioning of those living under the shadow of the conflict.

There are far-reaching indications that prolonged exposure has led to heightened levels of psychological distress and threat perceptions in both populations. We found that conflict exposure fuels mental health issues and significant disruption to the functioning and lives of large percentages of the affected populations. Israeli Jews reported lower levels of exposure to political violence and greater willingness to compromise for peace. Interestingly, Israeli Jews and Palestinians reported similar levels of threat perceptions.

Despite existing assumptions in political scholarship that the sufferings of individuals exposed to violence play a minor role in larger geo-political decision making, our study of Israelis and Palestinians points to such individual-level outcomes as key micro-foundations of conflict. Our work extends previous research on political attitudes among civilians living amidst political violence by connecting individual trauma subsequent to such violence with collective attitudes towards peace and compromise.

A key factor connecting exposure to political violence to attitudes towards peace is perceptions of threat— that is, the appraisal of danger that the “other” poses to the life or well-being of the individual or to the security or self-concept of the group. Threat perceptions are heightened in situations of prolonged conflict. Specifically, exposure to political violence leads people to feel vulnerable and threatened – feelings that people seek to buffer via defensive coping attitudes aimed at protecting the self.

These attitudes can include inflexibility, stubbornness, and unwillingness to compromise. In the political sphere, this inflexible attitude toward compromise can become entrenched in political discourse, as seen, for example, in the classic arguments between hawks and doves, its huge impact on public opinion and the heavy mental health toll paid by civilians. Exposure to increased violence and conflict-related mental-health issues thus makes both Israelis and Palestinians less willing to negotiate and compromise – hence perpetuating the continued cycle of hatred and aggression between the two peoples.

Civilian casualties in and of themselves constitute impediments to breaking the cycle of violence, as affected civilians and their communities become increasingly resistant to peace. Hardening their hearts by adopting defensive attitudes aimed at protecting the self may be the most effective means for individuals victimised by violence to help themselves. However, only by changing those dynamics can we hope to create a psychological-societal infrastructure capable of sustaining formal political agreements in conflict-ridden regions of the world.

Our work provides useful guidance for practitioners seeking to advocate peace. The findings highlight the role played by exposure to political violence in acting as a barrier to peace. It demonstrates the importance of removing violence, particularly violence directed at civilians, from the political landscape. In addition, our findings emphasise that actions aimed at reducing threat perceptions are crucial to the success of any peace negotiations. As a start in this direction, acknowledging and legitimising the losses of the other side is imperative for building trust and support in those constituencies that find moving towards peace most challenging.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Federica Mogherini and Israeli Foreign Minister , Credit: EEAS (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Fd9Cyu

_________________________________

Daphna Canetti – University of Haifa

Daphna Canetti – University of Haifa

Daphna Canetti is an associate professor at the School of Political Science, University of Haifa. She was a visiting professor in the Department of Political Science and the MacMillan Center, Yale University. Her research interests, for which she has secured over $2.5 million in funding, focus on the micro-foundations of conflict including the impact of individual-level exposure to terror and political violence on political attitudes. Her recent publications include articles in the British Journal of Political Science, The American Journal of Political Science and The Lancet.

Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler – Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya

Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler – Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya

Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler is an assistant professor in the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy, and Strategy at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, Israel, and a Senior Researcher at the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT). Her research focuses on the processes underpinning political extremism and political violence, with a particular emphasis on Israel.

Stevan Hobfoll – Rush Medical College

Stevan Hobfoll – Rush Medical College

Stevan Hobfoll is a distinguished professor of psychology and the Judd and Marjorie Weinberg Presidential Professor and Chair of the Department of Behavioral Sciences at Rush Medical College in Chicago. He has authored and edited 12 books, including Traumatic Stress,The Ecology of Stress, and Stress, Culture, and Community: The Psychology and Philosophy of Stress. In addition, he has authored over 250 journal articles and book chapters.

1 Comments