On 11 January, Croatia will hold a second round of voting to elect the country’s next President. Višeslav Raos provides a comprehensive preview of the vote, noting that the elections are expected to give a clear indication of how the country’s upcoming parliamentary elections might go later in the year.

On 11 January, Croatia will hold a second round of voting to elect the country’s next President. Višeslav Raos provides a comprehensive preview of the vote, noting that the elections are expected to give a clear indication of how the country’s upcoming parliamentary elections might go later in the year.

On 11 January, Croatian voters will decide whether the country’s incumbent President, Social Democrat Ivo Josipović (57), a law professor and composer of classical music, will retain his post or have to pass the baton to Christian Democrat Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović (46), former Minister of European Affairs, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy at NATO (the first woman to hold a senior post in the Alliance).

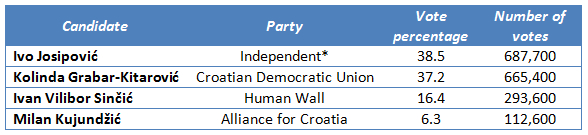

In the first round of the election, held on 28 December, Josipović gained some 20 thousand more votes than his main challenger Grabar-Kitarović, leaving behind a 25-year old Eurosceptic activist against home evictions, Ivan Vilibor Sinčić, and national conservative physician Milan Kujundžić. The Table below shows the result of the first round of voting.

Table: Result of the first round of the 2014-15 Croatian presidential election

Note: Ivo Josipović is nominally independent but was nominated by the Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP). For more information on the other parties see: Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), Human Wall, and Alliance for Croatia. Vote percentages are rounded to one decimal place and number of votes to nearest hundred.

Never was a presidential election in Croatia such a close-run challenge. During the 1990s, Croatia had a semi-presidential system, with presidential executive powers similar to those of its French counterpart. Franjo Tuđman won both elections (1992, 1997) in the first round, leaving his challengers behind with large margins (almost 34.9 per cent in 1992 and 40.4 per cent in 1997).

His successor, Stjepan Mesić, saw his presidential powers reduced due to constitutional changes in 2000 and the transformation towards a parliamentary system. Although winning both elections only after a runoff, Mesić also defeated his competitors by sizeable margins – in 2000 he had a 13.4 point advantage in the first round and just over a 12 point advantage in the second round, while in 2005 he won the first round with a 28.6 per cent margin and the second round with just under a 31.9 per cent margin. Josipović won his first term by a lead of over 17.6 per cent in the first round and just over 20.5 per cent in the second round.

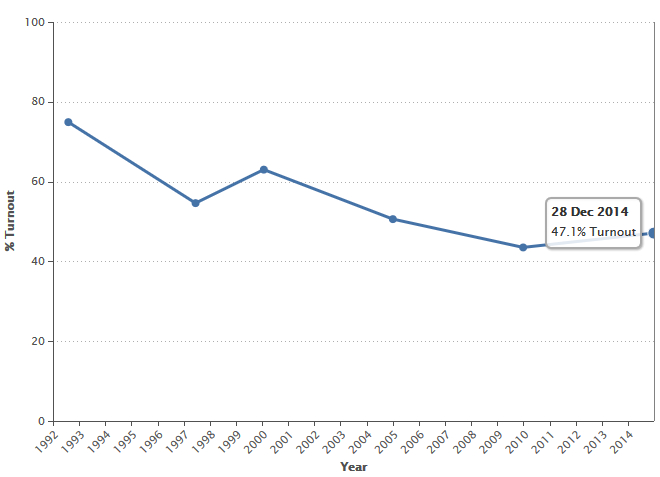

As the Chart below shows, presidential elections in Croatia are clearly second-order elections, attracting less than half of the electorate to voting stations and deciding who will enter an office with only limited powers in foreign and security policy. However, the two main political blocs – the centre-left, gathered around the Social Democratic Party (SDP, Party of European Socialists member) and the centre-right, grouped around the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ, European People’s Party member) – view them as midterm elections. The outcome of this Sunday’s poll is expected to indicate whether the pendulum of Croatia’s electorate will swing to the left or to the right at the upcoming parliamentary elections, likely to be held in December 2015.

Chart: Turnout in first round of Croatian presidential elections (1992 – 2014)

Note: This chart was generated using the Political Data Yearbook: Interactive (part of the European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook) available online at http://politicaldatayearbook.com

The candidates

The reelection bid of president Josipović (former SDP member, now officially independent, as he is constitutionally barred from being a party member while in office) is supported by the four government parties – SDP, social liberal Croatian People’s Party-Liberal Democrats (HNS) and regionalist liberal Istrian Democratic Assembly (IDS) (both Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe members), as well as the single-issue Croatian Party of Pensioners (HSU). Other parliamentary parties that support his candidacy include the opposition left-wing Croatian Labourists – Labour Party (European United Left – Nordic Green Left) and the green alternative Croatian Sustainable Development party (OraH) (European Green Party). Major watchdog and human rights advocacy NGOs in the country support the incumbent. He also has unofficial backing by many mainstream journalists. Former president Stjepan Mesić (2000-2010) has endorsed Josipović as well.

Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović enjoys the support of a wide centre right coalition, which includes not just HDZ, but also the agrarian Croatian Peasant Party (HSS, European People’s Party), the conservative liberal Croatian Social Liberal Party (Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe member), as well as several small national conservative parties. The Catholic Church, as well as several Christian non-governmental organisations have also given her strong informal support. War veterans, as well the vast majority of voters living abroad also overwhelmingly support her presidential bid. Furthermore, senior officials of the European People’s Party have endorsed Grabar-Kitarović.

The campaigns

Ivo Josipović has run his campaign on a platform of constitutional reform. Although he has not yet publicised his exact proposals for constitutional amendments, he has emphasised several aspects, including legislative veto powers for the President, regionalisation of the country, and a new electoral system that would elect half of MPs through a first-past-the-post system, while the other half would be elected on party lists through preferential voting.

Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović has consistently attempted to make Josipović accountable for the poor economic record of the government, led by his fellow Social Democrat Zoran Milanović. She opposes constitutional reform and larger presidential powers. Instead, Grabar-Kitarović asserts that Josipović has not made use of existing powers during his first term. Thus, she maintains that he should have used his constitutional right to call for an extraordinary government meeting on pressing social and economic issues in Croatia. Besides that, she has heavily criticised Josipović’s policy towards Serbia, claiming that he has not managed to resolve any outstanding bilateral issues, especially the question of Croatian citizens who went missing during the war. This is part of a larger policy disagreement between HDZ and SDP, where HDZ politicians maintain that the Social Democrats focus too much on the ex-Yugoslav neighbourhood and neglect strategic relations with Western allies such as Germany and the United States.

There are three main features of the second round campaign. First, both candidates have regularly discussed issues that are outside of presidential powers, but which instead sit within the domain of the government. Long years of recession have led Croatian voters to expect the President to ensure a “better life”, i.e. to work towards economic recovery and social cohesion. Thus, the media often pushes both candidates to focus their campaigns on unrealistic social and economic promises. The emphasis on social and economic issues also reflects the wish of both candidates to lure protest voters who cast their ballots for Sinčić in the first round. However, Sinčić has called his voters to abstain from elections or to write in his name on the ballots, rendering them invalid.

Second, both the centre left and the centre right bloc have portrayed the presidential election as a fundamental decision about the future course of the whole of Croatian society. This includes a great deal of scaremongering. Supporters of Josipović maintain that he must win in order to prevent the return of HDZ to government and they have placed great emphasis on the purported connection of the present HDZ leadership and its candidate with the former party leader and prime minister (2003-2009) Ivo Sanader, who is currently serving a prison sentence for high-level corruption. Alternatively, supporters of Grabar-Kitarović have said that she must win in order to prevent the “Reds” (Social Democrats) from reshaping the country according to their fashion, underlining the communist past of the current president and his co-workers, as well as their rather positive views of the Yugoslav period.

Third, the tone of the last leg of the campaign has become much harsher than it was in the initial period of campaigning. This has included personal smears over social networks and numerous attempts to discredit the other side by leaking supposedly controversial information to friendly journalists. In addition, Grabar-Kitarović has been a target of several sexist comments by high-ranking Social Democrats, including the Prime Minister.

The mobilisation capacity of the two main parties will no doubt have a decisive impact on the final election result. While HDZ has a massive party organisation, the SDP functions as a cadre party, maintaining a small, elite membership. Thus, Grabar-Kitarović might expect a greater boost in support from a stronger presence of party members on the ground. An unexpected heavy snow blizzard on the day of the first round prevented many people from casting their votes. While some analysts claim that the expected larger turnout in the second round will favour Josipović, others have noted that foul weather in the first round mostly affected elderly voters in rural areas who generally support Grabar-Kitarović.

Ultimately, if Josipović stays in office, this will help the highly unpopular Milanović cabinet to stay in power, avoid early elections, and delay intraparty struggles among the Social Democrats. However if Grabar-Kitarović wins the election, this will pave the way to a HDZ-led government after the parliamentary elections, just as Josipović’s success in 2010 meant the downfall of Jadranka Kosor (HDZ Prime Minister from 2009 to 2011) and enabled Milanović’s sweeping 2011 victory.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: © European Union 2013 – European Parliament (CC-BY-SA-ND-NC-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1BS4tpJ

_________________________________

Višeslav Raos – University of Zagreb

Višeslav Raos – University of Zagreb

Dr Višeslav Raos is a Senior Research and Teaching Fellow at the Faculty of Political Science, University of Zagreb. His main research interests include comparative European electoral and party politics, as well as processes of Europeanisation and democratisation in post-communist Europe.