Following Syriza’s election victory in Greece in January, and strong polling ratings for Podemos in Spain, are radical left parties becoming a stronger force in European politics? Luke March writes on the electoral performance of the radical left since the financial crisis. He notes that while a Syriza-style ‘surge’ remains unlikely for most radical left parties, there is fertile ground for their policies, with a significant percentage of voters in European countries self-identifying with left-wing political ideologies.

Following Syriza’s election victory in Greece in January, and strong polling ratings for Podemos in Spain, are radical left parties becoming a stronger force in European politics? Luke March writes on the electoral performance of the radical left since the financial crisis. He notes that while a Syriza-style ‘surge’ remains unlikely for most radical left parties, there is fertile ground for their policies, with a significant percentage of voters in European countries self-identifying with left-wing political ideologies.

For years now, several analysts (including me) have been proclaiming that the radical left is on the upswing in European party systems. However, reality has often confounded the prognosis, with electoral dividends from the Great Recession meagre, and every success counteracted by an apparent debacle. Certainly, politically, it is the right and austerity programmes that have dominated the crisis response, leading to the suspicion that the radical left had passed up a perfect opportunity to exploit capitalism’s travails.

Until now. Syriza’s stunning victory in the Greek legislative elections elected the first anti-austerity radical left government within the EU, at a time when the austerity consensus is under sustained assault from many angles. This has led to a profusion of sympathetic articles proclaiming that Syriza ‘magic equation’ will usher in a sea change in European politics, with a wave of hope and solidarity transforming Europe and finally undermining TINA (Thatcher’s adage that ‘There is No Alternative’ to neo-liberal transformation). Of course, TINA has been proclaimed dead before (particularly after the 1999 Seattle protests), and if simply asserting austerity’s demise (however forcefully) were enough to transform Europe, the left would have done so long ago.

A closer focus on the strengths and weaknesses of the European radical left shows that Syriza remains exceptional and its success is unlikely to be repeated imminently anywhere else, even if activists draw specific lessons as well as inspiration. Similarly, dramatic ruptures in European politics remain remote possibilities. Nevertheless, the longer-term prospects for the radical left will continue to improve, especially if Syriza’s governing experience offers benefits both to the Greek population and the wider European left alike.

The mosaic left – from movement to mutation

Today’s European radical left is a ‘mosaic left’ – a constellation of variegated parties and movements from motley backgrounds. There have been concerted efforts to develop common policies and networks, and still more importantly to bridge chasms between different ideological traditions, both in forming new electorally-focused parties which are coalitions of different tendencies and in emphasising as never before European nuclei of common action (e.g. the European Social Forums, the GUE/NGL European parliamentary group and the European Left Party). This radical left is no longer in crisis and decline, as it was until the 2000s, and the emphasis has shifted from (eternal) fragmentation to limited fusion. There has even been a significant uptick in party performance from the mid-2000s with parties increasing their vote share by over 50 per cent on average since the onset of the Great Recession, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. European radical left parties’ national electoral performance (September 2008-January 2014)

Note: Parties marked with * were in coalition. Calculations from www.parties-and-elections.eu. Parliamentary parties only. Note that the Latvian Socialist Party did not compete in the 2014 elections.

Nevertheless, aggregate growth can’t conceal inconsistency. A ten per cent average vote share is not negligible, but it is much less impressive when Syriza, Harmony Centre (a coalition between the larger Social Democrats and the Latvian Socialist Party which the latter has now left) and the former Soviet bloc (where historical legacy helps increase party support) are excluded. The radical left tends to do better in poorer and/or smaller countries, and is regularly dwarfed by the radical right in some of the more prosperous/larger countries (e.g. France, Italy and the UK).

Iceland excepted, the Nordic countries are no longer a zone of particular strength. The performance of the radical left in the 2014 European elections is similarly patchwork. On one hand, the GUE/NGL group was one of the winners of the elections, increasing its seat share from 4.8 per cent to 6.9 per cent and, with 52 seats, becoming the biggest radical left group in the EP since 1986, broadening its membership to 14 countries, far beyond the Latin communist core of the 1980s and early 1990s. On the other hand, in the 1980s it had nearly 10 per cent of the EP’s total seats. Moreover, its total is disproportionately boosted by stellar results in Greece and Spain (17 MEPs). Its current diverse makeup includes parochial, regionalist and nationalist members unlikely to help build a true radical left family, which hardly implies that the group will overcome its record as one of the EP’s least cohesive groups.

More troublingly, the radical left no longer exists as a movement in the pre-1989 sense, with (albeit in few European countries) strongly institutionalised parties embedded in subcultures with a panoply of affiliated social organisations. This is why some from the Marxist-Leninist tradition regard the radical left as still in deep crisis, summarily dismissing the achievements of what they regard as electoralist, ‘left reformist’ and even ‘centrist’ parties with weak social bases incapable of exploiting class discontent.

However, the fact remains that for much of the last two decades, genuine protest movements, even when motivated by social justice sentiment, have largely bypassed organised political parties, even those of the radical left, and even (still infused by the spirit of ‘68) have seen them as ossified institutions of the ‘system’ rather than as part of the solution. Even mass demonstrations in which trade unions and parties of the left have played key roles have often failed to bear obvious electoral dividends (e.g. the anti-austerity general strikes in Portugal in 2012-3 led to marginal growth for the Socialist Party and Communist Party, and a collapse in the Left Bloc vote in the 2014 Euro elections). Growing exceptions to this rule are younger radical left groups among protests in Eastern Europe (e.g. Bosnia, Croatia and above all Slovenia, where the United Left broke into parliamentary politics in 2014).

Yet even today, most European countries have some half-dozen competing radical left parties, usually individually miniscule but salami-slicing an already fragile vote. Several of the earlier generation of ‘broad left’ parties uniting different ideological traditions (e.g. Rifondazione Comunista, the Scottish Socialist Party and the Portuguese Left Bloc) found schismatic traditions stubbornly persistent and have foundered as a result (the former two now on the edge of oblivion).

Even some of the larger, more established parties such as the German Die Linke and Dutch Socialist Party have struggled to increase their perspectives during the crisis. Gradual moderation to offer governing perspectives has often risked disappointing more radical supporters while failing to fully convince new voters and coalition partners that they mean business, while the business community itself often weighs in heavily against the radical left and their supposedly obsolete, ‘extreme’ or ‘far left’ policies. At the same time the radical right often benefits more than the radical left, mainly because they are more ideologically flexible than the left and can appropriate left-wing arguments (defence of the welfare state, protection of workers) while the left often struggles to come up with a popular response to right-wing arguments. Repugnant though anti-immigration sentiment is, it can be electorally dynamic in a way that international solidarity is not.

At the same time, Syriza’s success is clearly somewhat exceptional, with a remarkably propitious combination of external and internal factors. Externally, as Stathis Kouvelakis has argued, Greece has suffered from an unprecedentedly violent socio-economic cataclysm resulting in political polarisation. Nowhere else in Europe (except Ukraine, for obviously very different reasons) has experienced anything like this. Relatedly, the complete collapse of the mainstream left PASOK because of its role in the imposition of the Troika’s policies (as well as in systemic corruption) has allowed Syriza to appropriate much of PASOK’s electoral space, activists and organisation, as well as leaving Syriza as one of the few untainted parties. Although social democrats are in trouble across Europe, nowhere else is ‘Pasokification’ (yet) on the horizon.

Simultaneously, Syriza possesses something of a magic formula for radical left party success; namely a populist ideology that projects defiance and can unite different ideological tendencies by articulating popular anger against the ‘establishment’; a pragmatic but principled approach to power (seeking government around clear anti-austerity principles, yet downplaying maximalist demands and proving ‘coalitionable’ with ideological opponents such as the Independent Greeks).

In addition, the party leadership’s calibre should not be dismissed lightly – it clearly (especially in Yanis Varoufakis) contains intelligent and charismatic individuals. Alexis Tsipras himself, although politically inexperienced, is ‘an effective leader but not a charismatic one’, presenting a solidity, statesman-like quality and charm. Obviously, the success of this leadership remains to be tested, and whether Tsipras has the stature or qualities to unite a potentially fractious party throughout future travails is unclear.

Not to be forgotten is the party’s strong ties with the anti-austerity ‘Squares’ movement, which allows Syriza to present itself as a genuinely ‘new’ force, even though its antecedent parties have been around for decades. For all that some analysts see this as a recent product of Ernesto Laclau, or a new left populist spectre haunting the continent, the fact is that many other successful radical left parties have aspired to such qualities over the last decade or more; few however have acquired all of them, nor benefitted from such a unique external environment.

Sustaining the Syriza surge

It is this singularity that means that there is unlikely to be an immediate ‘Syriza’ surge elsewhere in Europe. As Table 2 shows, only in Spain and perhaps Denmark, are we likely to see dramatic gains for the radical left in 2015 elections (although the quasi-left Sinn Féin has topped some recent Irish polls for the 2016 elections).

Podemos is often portrayed as the next Syriza, and indeed Podemoseven possesses some advantages over Syriza (a more developed populist image as the defender of popular ‘common sense’, a still more charismatic and media-friendly leader in Pablo Iglesias, a centralised party structure, organic links with the anti-austerity Indignados and a greater authenticity as a ‘new’ force battling the corrupt establishment ‘caste’). That said, the barriers are still formidable, with the Spanish Socialists much more resilient than PASOK (‘badly beaten but not defeated’), a modest economic recovery in progress, and the presence of the established United Left party likely to complicate matters further. Indeed, Podemos’ early poll rise has started to stall.

Table 2. Legislative elections forthcoming in 2015 (EU countries)

Source: adapted from Chiocchetti (2015)

In the longer run Syriza’s victory can clearly have a galvanising effect elsewhere, as indeed it already has: Tsipras has already emerged as a left-wing figurehead, leading the European Left Party in the 2014 Euro elections, and inspiring a ‘Tsipras List’ to unite the fractious Italian left. But sustaining this figurehead status will depend on the longer-term performance of the Syriza government, at the time of writing entirely unclear, as Greece and EU ‘have become stuck in a passive-aggressive standoffthat has made serious negotiation impossible’.

Remember that Syriza is the first anti-austerity but not the first radical left government in Europe – such parties have governed alone in Cyprus and Moldova, as well as being in coalition in a half-dozen other countries in the last decade, although they have been satisfied with meagre adjustments to the neo-liberal status quo. If Syriza manages to gain even limited respite from Greece’s debt burden that allows it to soften domestic conditions and contribute to rolling back austerity elsewhere, then this will be a comparative victory that can contribute to a credibility breakthrough for the radical left, and such parties’ increasing inclusion in governmental calculations elsewhere.

Such an outcome is devoutly wished by many, not just on the radical left – the prestigious US Foreign Affairs journal, hardly a bastion of Marxism, even called on the EU to make ‘some sort of deal with Syriza’, and (unlike many analyses) saw the radical left as a lesser evil than the radical right. On the other hand, if the EU continues playing hardball and the ‘Grexit’ scenario ensues or Syriza ends up capitulating to EU demands, this risks undermining almost all the achievements Syriza has made to date and reinforcing the mainstream view of the radical left as an economic pariah. But the radical right may be the chief beneficiary, not least in Greece itself.

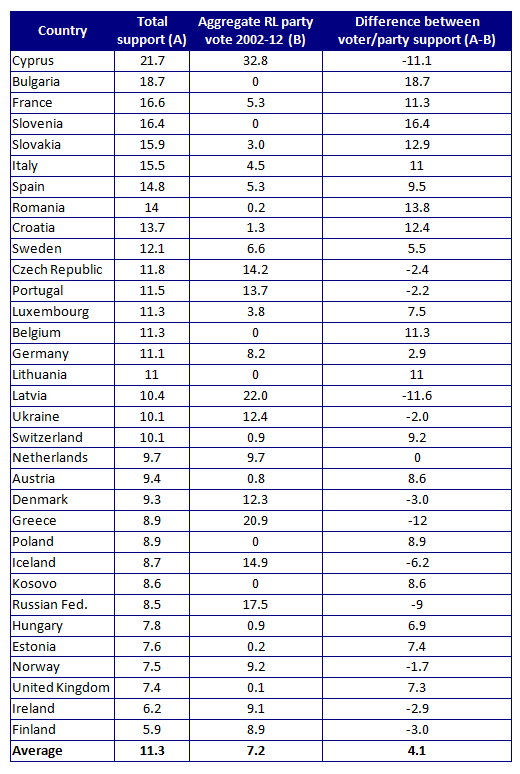

That said, the longer-term opportunities for the radical left will remain brighter than for decades. After all, as Table 3 shows, support for radical left ideologies is scarcely negligible in Europe now.

Table 3. Percentage of people who support radical left ideologies and average vote share for radical left parties in European countries

Note: Column A shows the percentage of individuals who identify as having a ‘radical left’ ideology (0-2 on a left-right scale in the European Social Survey 2002-12). Column B shows the average percentage vote share for radical left (RL) parties in elections during this period.

Whereas one obviously cannot directly extrapolate party success from individual level data, the implication is that (particularly when protest voters are added in), the potential vote for such parties is in the vast majority of countries considerably greater than their achieved success. Even in a notionally ‘post-austerity’ Europe, inequality, poverty and corruption will scarcely be dormant issues. And whatever Syriza’s actual policy successes prove to be, its electoral performance demonstrates a ‘success formula’ of populism, principle and pragmatism that other parties may emulate more explicitly than before. If we add in the stirrings of radical left protest in Eastern Europe, then Syriza will be the first but not the last party of the anti-austerity left to gain power in Europe.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: An earlier version of this article appeared at the EPERN blog run by the University of Sussex. The article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Uwe Hiksch (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1BoX6Ej

_________________________________

Luke March – University of Edinburgh

Luke March – University of Edinburgh

Luke March is Senior Lecturer in Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics, and Deputy Director of the Princess Dashkova Russia Centre in the School of Social and Political Science at the University of Edinburgh. His publications include Radical Left Parties in Europe (Routledge, 2011), and The Communist Party in Post-Soviet Russia(Manchester University Press, 2002).