How would a British exit from the EU affect the UK’s economy? Swati Dhingra, Gianmarco Ottaviano and Thomas Sampson outline the economic consequences of a Brexit, writing that reduced integration with EU countries is likely to cost the UK economy far more than is gained from lower contributions to the EU budget.

How would a British exit from the EU affect the UK’s economy? Swati Dhingra, Gianmarco Ottaviano and Thomas Sampson outline the economic consequences of a Brexit, writing that reduced integration with EU countries is likely to cost the UK economy far more than is gained from lower contributions to the EU budget.

The direction of UK trade policy with its biggest trade partner – the EU – will be decided in the upcoming general election. The Conservatives are committed to holding an ‘in-or-out’ referendum on membership by 2017 while Labour and the Liberal Democrats have opposed this, but how would Britain’s exit from the EU affect the UK economy and the income of UK citizens?

Brexit would harm the UK economy primarily by reducing trade with EU countries. Leaving the EU would also prevent the UK from benefiting from future free trade agreements negotiated by the EU, such as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership currently being negotiated with the United States. Finally, Brexit would reduce the attractiveness of the UK for foreign companies.

Jumping off the trade train

The best understood channel through which Brexit would affect the UK economy is via changes in UK trade. EU membership has reduced trade barriers between the UK and EU countries, leading to increased trade. When the UK joined the European Economic Community in 1973, just over 30 per cent of UK exports went to the EU. By 2008, over 50 per cent of UK exports went to EU countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of UK trade with EU countries

Note: Data covers trade with Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden.

Note: Data covers trade with Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden.

Using a quantitative model of the global economy, we analyse two scenarios for how leaving the EU would affect trade costs:

- An optimistic scenario, in which the UK continues to have a free trade agreement (FTA) with the EU much like Switzerland and Norway currently do through the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

- A pessimistic scenario, in which the UK is not able to negotiate such favourable terms and there are larger increases in trade costs.

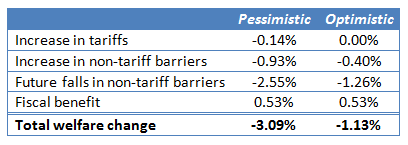

Table 1 summarises the results of our analysis for the impact of changes in trade barriers on incomes in the UK. In the optimistic scenario, there is an overall welfare loss of 1.1 per cent, which is driven by current and future changes in non-tariff barriers. Non-tariff barriers play a particularly important role in restricting trade in service industries such as finance and accounting, an area where the UK is a major exporter.

In the pessimistic scenario, the overall loss swells to 3.1 per cent, with most of the impact coming from non-tariff barriers (2.55 per cent). Leaving the EU would increase non-tariff barriers to trade (arising from different regulations, border controls, etc.) and reduce the UK’s ability to participate in future steps toward deeper integration in the EU. The costs of reduced trade far outweigh the fiscal savings. In cash terms, the loss is £50 billion in the pessimistic scenario and a still substantial £18 billion in the optimistic scenario.

Table 1: The effect of a ‘Brexit’ on UK welfare (static gains)

Note: Welfare measured by change in real consumption in the UK. Source: Ottaviano et al, 2014.

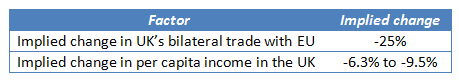

While the estimates of Table 1 directly relate to tariff and non-tariff barriers to welfare, they do not account for the dynamic gains from trade such as productivity growth from trade and the impact of other channels (such as FDI and transaction costs). Baier et al find that after controlling for other determinants of bilateral trade, EU member states trade 40 per cent more with other EU countries than they do with members of EFTA. Combining this with estimates that a 1 per cent decline in trade reduces income by between 0.5 per cent and 0.75 per cent implies that leaving the EU and joining EFTA will reduce UK income by 6.3 per cent to 9.5 per cent.

Table 2: The implied changes from leaving the EU and joining the EFTA on UK welfare

Note: Welfare measured as change in per capita consumption in the UK. Source: Ottaviano et al, 2014.

These estimates are much higher than the costs obtained from the static model, which suggests that the dynamic gains from trade are important. To put these numbers in perspective, during the 2008-09 global financial crisis the UK’s GDP fell by around 7 per cent.

Missing the next trade train?

It is sometimes argued that Brexit would allow the UK to increase trade with fast-growing economies such as China and India and with other important trade partners such the US and Japan. Being part of the EU does not restrict the ability of UK companies to trade with the rest of the world, and our analysis above accounts for the effects of Brexit on both trade with the EU and trade with the rest of the world. The EU is currently negotiating major new free trade agreements with the United States and with Japan. If the UK leaves the EU, it will not benefit from these and other FTAs negotiated by the EU in future.

CEP researchers have quantified the impact of recent EU FTAs on consumers in the UK. Consumer prices fell by 0.5 per cent for UK consumers as a result of FTAs negotiated by the EU with trade partners that are not EU members, saving UK consumers £5.3 billion per year. Based on this historical experience, the FTAs with the US and Japan would save UK households £6.3 billion every year. It is unlikely that these benefits would be as high if the UK were to negotiate alone. The size of the EU economy gives it a stronger bargaining position in trade negotiations than the UK would have on its own.

Foreign direct investment and immigration

Two further issues are how Brexit might affect investment and net migration into the UK. Part of the attraction of the UK for foreign companies is as an export platform to the rest of the EU, so if the UK is outside the trading bloc, this position is likely to be threatened. This matters because foreign multinationals tend to be high productivity firms and they bring new technologies and management skills with them. Given the large sunk costs involved in FDI, the uncertainty generated by the possibility of an in-or-out referendum may have a negative impact on investment in the run-up to the vote.

An argument used to support Brexit is that immigration from the EU has harmed UK-born workers in terms of jobs, wages and access to public services. But there is no compelling evidence that these negative effects exist (as shown in CEP’s Election Analysis of immigration and the UK labour market). Economically, migration acts much like trade, as people tend to move to countries where they can be more productive and earn higher incomes, increasing total welfare. Restricting this mobility will, just like restricting trade, reduce overall UK welfare. Di Giovanni et al find that the maximum size of such effects would be a loss of 1.5 per cent of income.

Conclusions

The economic consequences for the UK from leaving the EU are complex. But reduced integration with EU countries is likely to cost the UK economy far more than is gained from lower contributions to the EU budget. Static losses due to lower trade with the EU would reduce UK GDP by between 1.1 per cent in an optimistic scenario and 3.1 per cent in a pessimistic one.

The losses due to lower FDI, less skilled immigration, and the dynamic consequences of reduced trade could also be substantial. Even if the UK maintained full access to the single market following Brexit, it would not have a seat at the table when the rules of the single market are decided. Staying in the EU may cause political trouble for the major parties; but if the UK leaves the EU, the economic trouble will be double.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is part of the CEP’s series of briefings on the policy issues in the May 2015 UK General Election and originally appeared at our sister site, British Politics and Policy at LSE. The article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1GN83nJ

_________________________________

Swati Dhingra – LSE

Swati Dhingra – LSE

Swati Dhingra is Lecturer in Economics at the LSE.

–

Gianmarco Ottaviano – LSE

Gianmarco Ottaviano – LSE

Gianmarco Ottaviano is Professor of Economics at the LSE.

–

Thomas Sampson – LSE

Thomas Sampson – LSE

Thomas Sampsonis Lecturer in Economics at the LSE.

A worthy article which ignores a large category of evidence. The EU sells more goods and services to the UK than the UK does to the EU. The EU would want the trading relationship to remain the same.

The EU may want the trading relationship to remain the same if it weren’t for the precedent it would be setting for other countries to leave. The economic arguments would not take precedence of the the political ones. Consider the Guillotine clause in Swiss-EU bilateral agreements and the debate (and some real consequences) around the implications of the 2014 Swiss referendum to limit immigration from the EU. If your argument we correct, EFTA members and the EU would have negotiated better trade deals. And as the article pointed out, “[e]ven if the UK maintained full access to the single market following Brexit, it would not have a seat at the table when the rules of the single market are decided.”

Britain joined the EEC, which then turned into the Eu.. Give it a few more years and they will once again rename it perhaps into the uSG (united states of Germany). Keep Britain in the common market, but independent as a nation. That’s the best way to go.

Worthy article, which misses the fact that should Britain leave the EU, Scotland would have the excuse for another referendum, the result of which would probably lead to the break up of the United Kingdom.

Wales enjoys significant inward investment from the EU, what would be their postition be ?

As for Northern Ireland…………

The EU’s share of global GDP has collapsed since 1980. That decline is set to continue according to organisations like the IMF and OECD. As the EU stagnates and lurches from one recession to another, our trade with it will continue to shrink.

In fact, UK exports going to the EU fell below 50% years ago. More recently…in the year to March 2015, 46.9% of UK exports went to the EU. In the 3 months to March 2015 (Q1) the proportion was 45.1%. In the month of March 2015 it was 41.7%.

https://www.uktradeinfo.com/Statistics/EUOverseasTrade/Pages/EuOTS.aspx

Of course, the UK’s exports to the EU are significantly overstated in the official trade statistics. UK exports to non-EU markets are being falsely classed as exports to the EU, simply because they were unloaded for transhipment in European ports.

HMRC has known about the ‘’Rotterdam-Antwerp’’ affect for years. But it makes no attempt to adjust the trade figures to reflect reality. It is highly likely that the UK’s true underlying exports to the EU are below 40% of the total. Some estimates put the figure as low as 35%.

The EU is a stagnating unemployment-ridden Customs Union. We should leave it, negotiate a free trade agreement and look to the world’s high-growth for our trading future.

As an island nation the UK has always depended on trade with the world. But we’re shackled to an uncompetitive protectionist inward-looking basket case. We should leave the unelected bureaucrats and political retreads to their process of managing Europe’s decline.

With respect, we’ve heard this argument many times before and the problems with it are the same as always. Nobody has any idea how large the Rotterdam effect actually is, but we certainly can’t just lop 10-15% of our EU exports off on account of it. For a start, a large amount of what we export through Rotterdam remains in the EU which still makes it an “EU export” even though it’s attributed to the wrong EU country. We know that around 50% of what we export to the Netherlands, for instance, is oil, and the bulk of that stays in the EU.

The ONS actually went into great detail about this subject in the 2013 figures and came to the conclusion that exports to the EU were somewhere between 46.4% and 50.4% of total UK exports (depending on how you account for the Rotterdam effect) so the idea that everyone ignores it when producing figures isn’t actually true. In fact we’ve been having this debate for about 20 years now so citing the Rotterdam effect as if it’s some little known flaw in our entire understanding of UK trade with the EU is several decades out of date as far as these arguments go.

However we can quibble about the exact percentages all we like, it still doesn’t get us to a point in which there ceases to be a very large benefit from us having open free trade with the rest of the single market. The other great problem in the argument you’re making is that it typically assumes that somehow a “free trade agreement” is just as valuable in terms of facilitating free trade as membership of the single market. A “free trade agreement” can be anything from a simple agreement on tariffs, to an extensive agreement in which we actively participate in the single market by implementing EU legislation (as Norway does). In the former case we don’t derive the same benefits as there would still be technical barriers to trade, in the latter case we’re essentially still implementing EU legislation but no longer have any say over what it is – which seems at best pointless from a self-determination perspective, and at worst an affront to our democracy.

And also with respect, your reply is totally unconvincing. I believe the ONS report you’re referring to is this one: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/uktrade/uk-trade/december-2014/sty-trade-rotterdam-effect-.html

The ONS itself highlights a huge anomaly in the volume of exports going to the Netherlands, which is totally out of proportion to its 17 million population. But it says: ‘’The anomaly could be attributed to the Rotterdam effect, however, there is no way of confirming this.’’ (It’s also a fact that the ONS report doesn’t even refer to that other giant port…Antwerp in Belgium!)

According to official HMRC trade statistics, the proportion of our exports going to the EU in Q1 2015 was 45%. Even accepting the ONS assertion of a 4% distortion that would take the figure down to 41%. And that ignores other misclassifications, such as non-EU exports transhipped via the port of Antwerp, the Netherlands distortion and the Belfast Harbour effect. (The latter relating to imports from outside the EU transhipped via Belfast Harbour to the Irish Republic and wrongly classed as UK -> EU Exports).

Your comment that ‘’….we certainly can’t just lop 10-15% off our exports to account for it’’ is a straw man. My original comment was much more circumspect and implied an adjustment of 5-10%. That range appears entirely reasonable. Some might say it is far too conservative.

Turning to the issue of free trade with the single market if we left the EU. The UK is the EU’s BIGGEST single global market. The other 27 EU member states (the EU27) export more to the UK than any other country on the planet.

The UK is a bigger market for EU goods even than the US. In 2014, total EU exports to the US were €311 billion….or £251 billion. But that included UK exports to the US of £43 billion. So the value of EU27 exports to the US was £208 billion. Whereas the EU27’s exports to the UK in 2014 were £220 billion!

It’s also a fact that in 2014 the EU27 had a trade surplus of £76 billion with the UK.

Ignoring the dreadful state the EU (and specially the Eurozone) is in, a trade deal that suits the UK would be agreed. We would comply with all necessary quality, environmental and safety regulations on products exported to the EU. In the same way we comply with the specific requirements of all the world’s markets we trade with. But we would be freed from the EU’s Acquis Communautaire. (And regulations on 90% of the UK’s economic activity (GDP) which is nothing to do with the EU).

The entire thrust of the second part of your comment is based on the principle that what we’re talking about is whether the UK would be able in principle to negotiate a free trade agreement with the EU. To make that case you’re citing (as is common in these arguments) the value of exports that the EU sends to the UK and trying to claim that because EU countries export a great deal to the UK it would be in their interest to have a free trade agreement (or even that the UK would have the upper hand in that discussion).

The problem with this is that firstly, nobody is disputing whether we can have a free trade agreement with the EU or not. I’m not going to repeat everything I said above, but I would advise reading the last paragraph again because your response has pretty much bypassed it entirely (in favour of repeating some fairly stock arguments).

Second, if you’re trying to make the common argument that the size of EU exports means the UK would be able to dictate terms to the EU in such a negotiation that’s a fairly straightforward misunderstanding. The principle that countries with a negative balance of trade have more influence in a negotiation makes about as much sense as claiming that because I buy all of my groceries from Tesco and sell them nothing I can therefore walk into a store and start demanding a knock down price on my shopping.

As has been stated countless times in articles far more eloquent than anything I could manage, what matters in a trade discussion isn’t which side exports a certain fraction more than they import, it’s the volume of trade. Our trade with the EU is (whatever percentage we settle on) a very large proportion of our total trade. The EU’s trade with the UK is many times smaller as a percentage of total EU trade.

But none of that matters to the point that was actually being made. The point is that we can’t simply talk in vague terms about getting some magical “free trade agreement” that would give us all of the benefits of EU membership with none of the costs. As I said above:

“A “free trade agreement” can be anything from a simple agreement on tariffs, to an extensive agreement in which we actively participate in the single market by implementing EU legislation (as Norway does). In the former case we don’t derive the same benefits as there would still be technical barriers to trade, in the latter case we’re essentially still implementing EU legislation but no longer have any say over what it is – which seems at best pointless from a self-determination perspective, and at worst an affront to our democracy.”

Of course the UK and EU would agree a free trade deal. Only people like Nick Clegg would try and suggest otherwise (as part of their ‘’project fear’’ over Brexit). The volume of trade is critical.

And, despite what you say, so is the direction of that trade. Tariffs, or customs duties, would disproportionately affect Europe’s large manufacturers. The CEO’s of VW-Audi, BMW, Mercedes, Siemens, Peugeot-Citroën, Renault and so on would be up in arms at any suggestion of a reversion to tariffs on their trade with us. As would millions of other businesses across Europe.

The EU would also be a laughing stock if it threw its toys out of the pram. Agreeing trade deals with countries like South Korea but refusing to agree one with its biggest global export market?! Please be serious. Then there are the WTO rules, which would prohibit the EU discriminating against the UK in trade terms after we left.

I’ve just re-read the last paragraph of your previous reply.

You’re basically asserting that there are advantages to EU membership over and above tariff-free access to the single market. But you don’t specify what these advantages are. Perhaps you’d care to do so now?

You also say we would still be implementing EU legislation. But you don’t say explain why that would be the case. Again, perhaps you would explain why a country which is no longer a party to the EU’s treaties would be obliged to implement its legislation?!

As I’ve already said, we would comply with all necessary quality, environmental and safety regulations on products exported to the EU. In the same way we comply with the specific requirements of all the world’s markets we trade with. But we would be freed from the EU’s Acquis Communautaire. (And regulations on 90% of the UK’s economic activity (GDP) which is nothing to do with the EU).

What I’m advocating is that we leave the EU and negotiate a free trade agreement with continuing access to the single market. We would of course comply with the rules applicable to that market. As we would have to if we’re finally able to negotiate our own trade deals with the world’s high-growth economies.

Regarding having any say over EU regulations, just how much influence do you think we have now?! The UK is one of 28 member states. In fact, being part of a one-size-fits-all regime is a major disadvantage for the UK, a trading island nation.

The UK’s influence in the Germano-Franco dominated EU is vastly overstated. We only had 8% of the votes in the Council prior to November 2014. That minimal influence hasn’t been enhanced by the new ‘’Lisbon’’ voting system and the introduction of procedures such as the blocking minority and the population double-lock.

At some point, people who advocate continued membership of the EU must stop relying on vague generalities and platitudes…and start addressing the specifics. They should also explain why they believe the UK should remain a member of an organisation which is a protectionist, inwardly-focused, uncompetitive, stagnating, job-destroying, debt-riddled Customs Union dinosaur which has already overseen a collapse in Europe’s share of world trade. And which, by the 2030s, will have reduced Europe to an economic irrelevance.

Your comment to Fig. 1 is wrong: “30%” corresponds to 1963, not to 1973. And it shows that the share of trade with the EU has now fallen approximately to the level it had in 1973. Brexit supporters would say: This statistics is not an argument for remaining but just the opposite.

@Louis “You’re basically asserting that there are advantages to EU membership over and above tariff-free access to the single market. But you don’t specify what these advantages are. Perhaps you’d care to do so now? You also say we would still be implementing EU legislation. But you don’t say explain why that would be the case. Again, perhaps you would explain why a country which is no longer a party to the EU’s treaties would be obliged to implement its legislation?!”

You’ve said that as if I’ve invented some novel argument for EU membership, when in reality I’m simply stating the basic principles that the single market is founded on. The entire purpose in the single market is that it’s more than an agreement on tariffs. The point in it is that you eliminate technical barriers to trade by eliminating regulatory inequalities. Instead of a business confronting 28 separate rules whenever they export to the single market they only have to confront one. That allows them to cut costs, removes barriers to free trade, increases competition (and so on).

As for implementing EU legislation, this is precisely what countries like Norway already do: they’ve negotiated access to the single market and implement EU legislation in most areas (save for a few opt-outs). Part of the reason for that is that when every other country in Europe is using a particular regulation you only create a trade barrier by pursuing a different course. The core benefit of EU membership in that context is that as a member you get to influence what those rules are, whereas countries like Norway have no say (hence their self-deprecating description of themselves as a “fax democracy”). Again, this is a very basic principle that you’ll hear stated regularly if you discuss this issue seriously so if you’ve never heard this argument before I would suggest becoming better acquainted with the pro-EU case before you decide to oppose it.

As for the idea that “we have no influence because we only have 8% of the votes” that’s little more than a misleading soundbite that’s been debunked on thousands of occasions. We have studies going back 15-20 years using advanced quantitative methods and detailed expert surveys that give us a good understanding of how EU negotiations in the Council go. They rarely end up in a voting situation in the first place as they’re based around consensual decision-making and there is no evidence, whatsoever, that the UK lacks influence relative to other states or is uniquely compelled into accepting legislation it opposes on a regular basis. Indeed using your argument you could just as easily claim that Germany has no influence in the EU due to the small percentage of votes it accounts for in the Council and I think we’d all agree that’s nonsense.

Great article, It seems to me that no enough is reported on the consequences of leaving and the cost of joining the free trade agreement

In short, Louis has covered almost everything in a fair and measured way.

The only forseeable reason for the EU (and perhaps we mean France) to block continuation of the existing trade arrangements – is pique.

EU business will not stop wanting to export to the UK.

Supposing France did block traffic – it goes via Belgium and Netherlands instead (Surely they would welcome the business?)

As for “influence”. That is a myth. QMV means that Britain cannot block EU laws.

The best “influence” is to be free to be different – with the results being evidence of whether Britain was right or wrong.

“They rarely end up in a voting situation in the first place as they’re based around consensual decision-making”

Consensus decision-making is amongst the worst for a fudged or bullied decision. Better to have a clear proposal and a vote.

Having sat on numerous school Governing Bodies (and similar) where “consensus” is expected, no-one is prepared to counter the Headteacher (or other leader) for fear of being branded “troublemaker”.

In reality “consensus” is often similar to the forced confession.

There may be scope for trimming around the edges, but the direction of travel remains unchanged – as in the EU and “ever closer union”.

“EU business will not stop wanting to export to the UK. Supposing France did block traffic – it goes via Belgium and Netherlands instead (Surely they would welcome the business?)”

With respect, this is the same incredibly primitive conception of what trade is that we always hear from the leave side. The general assumption seems to be that the only thing that matters in terms of trade is whether we’re allowed to do it or not – and so long as the French don’t send their navy to blockade our ports we’re fine, as if we’re still living in the 18th century.

In the real world, what matters to modern trade is 1) tariffs and 2) regulatory barriers. The likelihood of the EU imposing tariffs on UK imports is very low. The likelihood of regulatory barriers developing however is extremely high. The EU is essentially an agreement between states to coordinate their regulations so it’s easier to export between members. If you aren’t implementing those regulations then you have to confront different rules from your domestic market every time you export (which entails a cost). If you are implementing those regulations then (like Norway) you’re half in/half out – using rules you have no say over to govern your own economy.

That’s the dilemma and it’s about time we took it seriously instead of dreaming up fantasy reasons for why we can have our cake and eat it. The idea of daring traders whizzing around a French navy blockade is about as relevant as claiming we need to leave the EU to escape Genghis Khan.

Harris,

Sorry, but its hard to “respect” such a belittling distortion of the “leave” arguments – so typical of integrationists – play the man and miss the ball.

“The likelihood of regulatory barriers developing however is extremely high”

In a world where the WTO is more important than the EU, what are the chances that the EU will introduce regulatory barriers that magically disadvantage British exporters while somehow allowing imports from the RoW?

“If you aren’t implementing those regulations then you have to confront different rules from your domestic market every time you export”

A) Cost of complying with various regulations was a general problem a few decades ago when domestic regulations were all over the place

B) The worst problem was protectionism with a country devising a regulation around existing indigenous products and against foreign products – bad for competition, bad for consumers and bad for innovation

This is less of a problem now because many if not most “standards” are now proposed by WORLD bodies NOT the EU.

So;

a) Any country that devises unique regulations risk exclusion from world trade.

b) Any country wanting real “influence” keeps its own seat on world trade bodies rather than delegate to a regional rep and hope they remember to make its point !

And the (nearly) old chestnut … German car manufacturers won’t want their best exportmarket, the UK, disrupted.

The fact that YOU conjour up references to 18thCentury and naval blockades is rather apt. The EU is the past. The world is the future.

Jesus, Jules !! get a brain if you can’t stand to look at the world outside your living room

1) the last round of worldwide agreements under the WTO umbrella was more than 2 decades ago, and it was mostly only about tariffs on manufactured goods

agricultural products are very much protected all over, either through tariffs, subsidies or regulations (ie: the TPP is all about harmonising regulations and if accepted, they will be phased out over 15-20 years)

the real added value is in services, but here it’s not really about tariffs, but regulations

,

and yes, one reason why the UK is banging about “economic reform” is because the EU hasn’t do as much progress as it expected to liberalize service products markets, because it’s very much subject to national regulations (though compared to the RoW, it’s pretty much liberal).

and services (financial or commercial) is very much where the UK shine in its trade

so, if it’s so slow when inside.

outside, it’ll be dead (ie: you would have as much influence as say Singapore or Switzerland or Jamaica)

2) no, countries or regions that devise “unique” or “special” regulations to protect their markets DO exist

actually, they are all over the place and constantly so

why do you think the TTIP is all about harmonising standards between the US and EU ?

and if a country or a regional organization decide to complain, it takes years of protracted negotiations, and only after exhausting plentiful of channels. but here comes the crust : the arbitration panel of the WTO not only takes further more years to reach agreement, because it’s nothing more than another political negotiation

ie : the hormone beef or the caribeean/south american bananas rows have been “trade dispute” for over 30 years

they aren’t “resolved” by any means, but each side agreed to “pay” an economic price in order to keep the stand off going on (that is to penalize other products/sectors rather than fully liberalize)

that is because the WTO is toothless, it only provide a veneer or legitimacy to any party that decides to take actions : the bigger an actor you are on the international scene, the more influence you have to implement the sanctions/decisions …

and here, money talks. a regional area of $14trillion is way more influential than a country of $2.5trillion

not because of the difference in numbers, but because it impact many more countries at a larger level

when you represent 10% of the trade of your partner, you are significantly important to them

but when you represent 50%+, you aren’t just important : you call the shots !! because any changes in the terms of trade will determine whether your partner is expanding or in recession

3) world bodies “propose” standards

ah ! indeed they “propose”

that doesn’t mean that they are implemented fully partially or none at all, even when assuming the members agree to those standards.

more often than not, the standards are “proposed” to reflect EXISTING standards by the most influential regional trade actors, that is the US and EU (ASEAN is more about status quo about national regulations than liberalization)

and when a dispute occurs, re-read my point 2)

not a single member country to my knowledge has EVER been excluded from the WTO (or its predecessor the GATT), irrespective of whatever long-running trade dispute or change of regulations

far-east asian countries are renowned for their byzantine regulations that have no other purposes but to protect domestic actors

the US is famous for using nationalism and “democratic oversight” (ah!!) to prevent foreign competition in domestic markets

in Europe, Greece is a classic example of how you pretend to play by the rules (ie: adopting legislation) but pretty much never implementing them, so much so it is in the bottom quartile of market liberalization the world over, yet where never called over it by their partners until the financial crisis

indeed, whether or not a regulatory standard is implemented anywhere in the world is entirely dependent on the commercial influence of its proponent(s)

4) your bumper-sticker slogans are actually quite revealing

post-nationalism is indeed modernity, and that’s what transnational organizations like the EU are

but banging about “sovereignty” (a fanciful myth is there were ever one in realpolitik) and nationalism is so yesterday

Regards,

”A pessimistic scenario, in which the UK is not able to negotiate such favourable terms and there are larger increases in trade costs”

So how does that work then ?

When we buy far more from them than they buy from us.

Are they going to penalise themselves ?

We buy more German cars than any other country.

Frau Merkel needs that income to prop up the failing Euro & to house all her new fakugees

I don’t know how many times we have to debunk the idea that having a trade deficit “buys you influence” before Eurosceptics will stop repeating it. The United States has a massive trade deficit with Thailand – does that mean Thailand can dictate terms to the US in a trade negotiation? Ukraine had a trade deficit with Russia when they were being held over a barrel over gas imports – how did that work out? If a small country with no export sector to speak of, that relied entirely on British imports to survive, entered a negotiation with us then do you think we’d be the ones lacking in influence?

As a principle it’s complete and utter nonsense (a bit like claiming because you buy your coffee from Starbucks and sell them nothing you can waltz in and start knocking a pound off the price) yet you can barely browse a comment section on the internet without someone presenting it as proof we’ll be demanding the world following Brexit. There really must be a better argument than this – I refuse to believe that UKIP have been dedicating their lives to this one issue for 20 years and that’s the best they can come up with.

I don’t know how many times we have to debunk the idea that – having “influence”requires submitting the UK to a higher (EU) law – initiated by bureaucrats and supported by foreign politicians that the British people cannot remove – before integrationists will stop repeating it.

If the EU was only about trade (like all other world regional trade bodies) …… but it isn’t.

The EU is political – with its laws reaching into every nook and cranny – affecting the local hairdresser with no international trade to speak of – instead of the EU’s laws being limited to cross-border trade (around 10% of the UK economy).

Over policies that affect 90% of the UK economy, REAL influence comes from being able to take independent action – with the results demonstrating what works and what doesn’t – not one-size-fits-all laws from Brussels.

As for cross-border trade, the idea that the 5th largest economy in the world cannot agree fair bi-lateral trade deals is absurd.

Remain scare stories that it would take a decade to agree new trade deals are equally absurd.

All existing Trade arrangements can remain the same until they change. How “uncertain” is that ?

If Trade was the ONLY issue (i.e not about democracy and sovereignty), AND the EU was an economic tiger, remaining might be tolerable

With faster growing countries such as India having a shared history and common language – along with the rest of the Commonwealth – then leaving an inward-looking EU on purely economic grounds should be a no-brainer.

The EU’s democratic deficit should make Leaving a slam-dunk certainty.

I have heard the arguments for and against leaving the EU,What I would like to hear from the remain camp is what the Uk would gain by remaining.I don`t mean the regurgitating of the usual “better at the table than outside”but more what positive improvments we would get.

“Brexit would harm the UK economy primarily by reducing trade with EU countries.”

Why would trade reduce?

All 22,000 EU laws embedded in UK law would stay in place – so UK exporters would remain compliant.

“Leaving the EU would also prevent the UK from benefiting from future free trade agreements negotiated by the EU”

The EU often takes much longer to negotiate trade agreements than two non-EU contries – so Britain could benefit . i.e negotiate independently and perhaps overtake the EU