Much of the discussion in the lead up to the 2015 Spanish general election has focused on the surge in support experienced by the left-wing Podemos, which has topped several opinion polls in recent months. However a sizeable jump in support for another smaller party, Ciudadanos, has raised the prospect of the election becoming a four party race between Podemos, Ciudadanos and the two traditionally dominant parties in Spanish politics, the PSOE and PP. Jose Javier Olivas writes on the emergence of Ciudadanos. He argues that while Podemos has received greater media attention, the more moderate and constructive reformist agenda pursued by Ciudadanos is likely to give them a better chance of shaping the actions of future Spanish governments.

Much of the discussion in the lead up to the 2015 Spanish general election has focused on the surge in support experienced by the left-wing Podemos, which has topped several opinion polls in recent months. However a sizeable jump in support for another smaller party, Ciudadanos, has raised the prospect of the election becoming a four party race between Podemos, Ciudadanos and the two traditionally dominant parties in Spanish politics, the PSOE and PP. Jose Javier Olivas writes on the emergence of Ciudadanos. He argues that while Podemos has received greater media attention, the more moderate and constructive reformist agenda pursued by Ciudadanos is likely to give them a better chance of shaping the actions of future Spanish governments.

The emergence of Ciudadanos or Ciutadans (‘Citizens’ in Spanish and Catalan) as a credible alternative to the People’s Party (PP) and Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) is one of the most significant events in the Spanish political arena in years. Although they may not have yet the level of support and media attention enjoyed by the other rising star in Spanish politics, Podemos, Ciudadanos’ impact on the political system and party dynamics may prove more decisive in the long run.

Ciudadanos are attracting disenchanted centre-left and centre-right voters. Their cambio sensato (‘sensible change’) approach offers a reformist agenda that can be considered a middle ground between the continuation of the system forged by PSOE and PP over three decades, and the more radical change proposed by the left leaning Podemos. Thus, if Podemos offer a revolution, Ciudadanos promise an evolution.

While Podemos’ campaign is somewhat backward looking and focuses almost entirely on attacking the misdeeds of the current political establishment, Ciudadanos are putting more effort into building a credible alternative programme and setting conditions for future pacts with other parties. Even their critics recognise that unlike most other Spanish parties, which tend to focus the debate on somewhat vague policy goals, Ciudadanos has launched their bid for government by discussing specific policies and policy instruments.

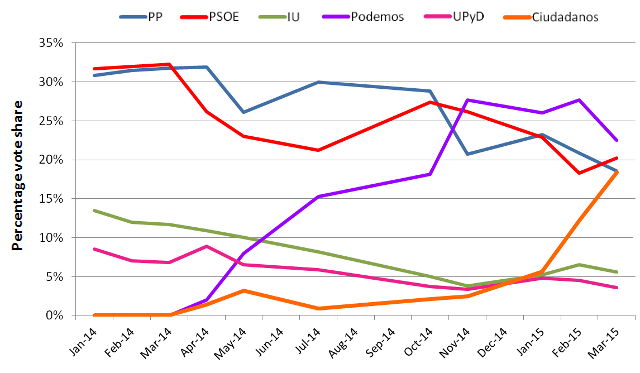

As the chart below shows, Podemos may end up gaining more seats in the next general election than Ciudadanos, but it seems increasingly likely that Ciudadanos will hold the key for Moncloa and many regional and local governments.

Chart: Evolution of voting intentions in Spain since January 2014

Source: Metroscopia – El País

Ciutadans de Catalunya (Citizens of Catalonia) was a party created in 2006 as a reaction against the nationalist movements (later turned secessionist) in Catalonia. They were initially considered a marginal party, generally ignored and even mocked by the media and other parties. They only obtained about 3 per cent of the votes and 3 seats in the 2006 and 2010 Catalan regional elections. However, their unambiguous message against the independence of Catalonia and the growing media exposure of their charismatic leader, Albert Rivera, allowed them to gain momentum.

In the 2012 snap elections for the Parliament of Catalonia, following the largest pro-independence mobilisations in Barcelona, Ciudadanos managed to get 7.6 per cent of the votes and 9 MPs. In the 2014 European Parliament Elections they obtained 3.6 per cent of the total Spanish vote and 2 MEPs. Ever since, the popularity of Ciudadanos has skyrocketed. In their first participation in the difficult Andalusian regional elections on 22 March 2015, they gained over 9 per cent of the votes and 9 MPs. Most importantly, their support elsewhere in Spain seems considerably higher. In one of the latest opinion polls this party appears fourth in vote intention (18.4 per cent) almost tied with the PP (18.6 per cent), PSOE (22.2 per cent) and the other big surprise, Podemos (22.5 per cent).

Who is Albert Rivera?

Albert Rivera is a young, yet experienced politician who has led the party since its foundational congress in 2006. Rivera’s profile is unusual for a party leader in Spain. Born in Barcelona in 1979 with a Catalan father and an Andalusian mother, in his youth, Rivera was a swimming champion of Catalonia and winner of the Spanish University Debate League. After graduating (Bachelor and Masters in Law) he worked as a lawyer for the biggest Catalan Bank, La Caixa. Rivera is a declared Europhile and atheist.

Despite his young age, Rivera has demonstrated during his career in Ciudadanos great resilience and composure. He overcame some early mistakes by the party and slowly managed to consolidate its organisation in a highly hostile environment. Their anti-nationalist agenda made Ciudadanos regular targets of insults, mockery and even death threats. Rivera is arguably the most eloquent politician in Spain, currently the leader with the highest approval rate. He has continuously demonstrated his excellent oratorical skills in the Catalan Parliament and Spanish media interviews and political debates. Rivera’s charisma is one of the main reasons why voters are switching to Ciudadanos.

Ciudadanos vs Podemos

It is difficult to speak about Ciudadanos without establishing comparisons with the other great phenomenon of Spanish politics: Podemos. Both are capitalising on the public discontent with the PSOE and PP. The economic crisis has undermined citizens’ trust in traditional parties who are considered co-responsible for Spain’s problems. Although Ciudadanos’ and Podemos’ diagnoses of the crisis share some similarities, including criticisms of corruption, clientelism and an ‘unfair’ electoral system, both parties differ widely in the solutions they propose.

Podemos promises radical changes and a break with the current constitutional status quo. They find inspiration in Syriza in Greece and some Latin American governments for many of their reformist policies. Ciudadanos propose a more quiet approach to reform, what they call ‘sensible change’. They feel comfortable with the current constitutional framework and prefer to draw lessons from the Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon models.

Podemos is conducting a very direct and aggressive campaign against the PP and PSOE. Its leader, Pablo Iglesias, recently claimed in a public rally that ‘heaven is not taken by consensus, it is taken by assault’. Podemos gambles on a large electoral victory and gives little room, if any, for post-election pacts with any of the big parties. However, the situation in Spain is less desperate and its electoral system differs widely from that of Greece. The decline of the PSOE and PP is slower than that of PASOK and New Democracy, and Podemos will not easily find an ‘external enemy’ against whom to rally Spanish voters.

Ciudadanos, aware that Spain is transitioning into a four-party system, are avoiding direct confrontation and keeping the door open for eventual pacts with any of the other parties. They criticise the corruption scandals and policy failures of the PP and PSOE but believe that sooner or later some agreements with them will be necessary. Their different, more constructive approach to opposition is a way to distinguish themselves from Podemos, prevent criticism in the likely scenario of negotiations, and avoid alienating voters still loyal to the two big parties. They understand that ruling Spain requires a sizeable share of centrist voters.

Ciudadanos, right or left?

The first great challenge for Ciudadanos is breaking the deeply entrenched left-right divide in Spanish politics. An important task ahead is to deflect some misconceptions regarding Ciudadanos’ ideological position, often employed as a means to discredit them. Ciudadanos has been often described by the media and political opponents as a right wing party. However, Ciudadanos is not the Podemos of the right as some haveclaimed. Ciudadanos was founded by a group of centre-left intellectuals concerned with the rise of nationalism in Catalonia. Although Rivera was once a PP-sympathiser, most of the ideological leaders of this project had been previously linked with left wing organisations. Their foundational manisfesto declares that the party’s ideology was inspired by ‘progressive liberalism and democratic socialism’.

Currently the party avoids stating publicly to be either on the left or right of the spectrum. After the 2014 EP elections Ciudadanos’ MEPs joined the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE). Some of their proposals seem to target a centre-right electorate (e.g. a maximum income tax of 40 per cent and the limitation of public health services for non-legal residents). However, their political agenda overall indicates a socially progressive angle (e.g. public education, laicism, fighting against inequality and job insecurity). Similarly, their centrist economic programme coordinated by the LSE Professor Luis Garicano and the former head of the Spanish financial markets watchdog, Manuel Conthe, emphasises the need for effective market regulation, social equality and a European pro-growth agenda.

New policy proposals and pacts with other parties will carry the risk of alienating either their centre-left or centre-right electorate. This is a delicate balance and any faux pas could compromise their image.

New challenges ahead

The months to come may prove eventful for the party. After their success in the Andalusian elections, Ciudadanos will enjoy hereafter much more media attention. This will increase the public scrutiny on the party and its candidates. Previously, Ciudadanos were not taken very seriously by any of the other national parties. But now Ciudadanos are stealing substantial numbers of votes from the UPyD, PP and PSOE, and eroding the chances of Podemos, IU and the peripheral nationalist parties to influence negotiations over the next government. Any scandal or gaffe will certainly be seized upon to hurt the party.

The accelerated process of growth and institutionalisation will make it more difficult to control mistakes. Thousands of new members have joined in the last few months. The party will likely have to deal with the (formal or informal) absorption of UPyD, whose refusal to form a coalition with Ciudadanos triggered a massive shift of votes and party members. Ciudadanos has introduced a six month probation period to grant full membership and is running background checks on prospective candidates. While Podemos’ fast growth has been closely controlled by their central executive, Ciudadanos has opted for a more decentralised and less hierarchical approach. The executive organisation team may soon be overwhelmed with the task of coordinating and monitoring such a fast growing party structure and its grassroots movements.

Ciudadanos not only need to recruit many new candidates and party officers, but also need to invest a great deal into training and supporting them. The party is mostly recruiting highly skilled professional (lawyers, engineers, professors, entrepreneurs) with very little or no previous experience in politics. This is part of the appeal of the party and an example of coherence with their message of change and longstanding criticisms of the Spanish political class (largely dominated by professional politicians). However, this choice is not without risks. The personal skills, education and previous professional careers of these new politicians may prove insufficient when facing opponents with much more experience in political communication and better understanding of the institutions.

Finally, Ciudadanos are thriving among urban middle-classes and have gained the support of many businessmen and intellectuals. The challenge for them is to match this growth in rural areas and among working-classes without sacrificing the core aspects of their programme or adopting a populist discourse.

Still, they have many reasons for optimism. In an extremely short period of time Ciudadanos have successfully transitioned from being a Catalan party focused on a single issue, fighting against Catalan nationalism, into a credible alternative to the PP, PSOE and Podemos at the national level. The economic crisis and loss of legitimacy experienced by the traditional parties have opened a window of opportunity in Spanish politics. Both Podemos and Ciudadanos are determined to seize this chance. Podemos’ radical discourse has granted them, so far, more headlines and disenchanted voters. However, Ciudadanos’ more moderate and constructive reformist agenda is likely to give them a better chance to shape the actions of future governments and to build long-term voters’ loyalty. This could be another case in which the tortoise ends up beating the hare.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1MvXD2B

_________________________________

Jose Javier Olivas – London School of Economics

Jose Javier Olivas – London School of Economics

Jose Javier Olivas is Associate to the Civil Society and Human Security Research Unit, at the LSE and author of Iberian Military Politics: Controlling the Armed Forces during Dictatorship and Democratisation (2014, London: Palgrave Macmillan) . He is also Co-founder and Editor of Euro Crisis in the Press and Director of the online voting and debate platform netivist.org

Very good article.

I’m Spanish, and we are living a political situation so different now.

Until now, there were only two parties with possibilities of being in the government: PP or PSOE, but since the European elections, as corruption scandals were being more and more, people were getting so angry, that there were many of them who were going to vote for Podemos, without knowing what its program nor ideology were, and Rivera was unknown, nowadays, that people are getting to know better both of them, Ciudadanos is growing fast.

“Podemos is conducting a very direct and aggressive campaign against the PP and PSOE” No, Podemos as what it is, communism re-branded, it is doing what communism always does: consider the opposition parties not as people that think different but as the enemy.That is why Podemos has troubles implementing the same type of discourse with Ciudadanos, a party that wants to regenerate the Democracy in Spain, because would expose the wolf that is hiding under the sheep skin. , .