What role does social media play in tensions between communities in Northern Ireland? Paul Reilly outlines findings from research on the use of Twitter during the ‘marching season’ in July 2014. He writes that while social media has often been used to reinforce divisions between communities in Northern Ireland, it can also be used to help defuse sectarian tensions.

What role does social media play in tensions between communities in Northern Ireland? Paul Reilly outlines findings from research on the use of Twitter during the ‘marching season’ in July 2014. He writes that while social media has often been used to reinforce divisions between communities in Northern Ireland, it can also be used to help defuse sectarian tensions.

On 12 July 2013, there were violent clashes between loyalist protesters and the Police Service of Northern Ireland after a ruling by the Parades Commission that prevented the return of an Orange Order parade past the Ardoyne shops in North Belfast. The subsequent failure of political representatives to broker a solution to this impasse, highlighted by the continued presence of a loyalist protest camp in nearby Twaddell Avenue, led many observers to fear that there would be a repeat of this violence the following year.

Tensions in the area were further raised when unionist and loyalist leaders announced that they were planning a ‘graduated response’ to the Parades Commission’s decision to alter the route of the return parade for the second year in a row. These plans were heavily criticised by nationalist residents’ groups, such as the Greater Ardoyne Residents’ Collective (GARC). By way of response, a member of GARC unsuccessfully tried to obtain a high court injunction to prevent the outward leg of the parade from passing the Ardoyne shops on the morning of 12 July.

Fears of a repeat of the sectarian clashes previously seen in Ardoyne and elsewhere were not realised in July 2014. Northern Ireland Secretary of State Teresa Villiers praised all sides for their role in delivering the most peaceful ‘Twelfth’ in recent times. Therefore, a recent study I have conducted, funded by the Northern Ireland Community Relations Council, was designed to investigate the ways in which the peaceful protests of loyalists and nationalist residents in July 2014 were digitally mediated. In particular, I focused on how users responded to rumours spread on Twitter, which were argued to have had a negative impact upon cross-community relations in areas such as North Belfast. The nature of the debate amongst these ‘tweeters’ was also investigated, with a specific focus on whether they used inflammatory, sectarian language in response to the events as they unfolded.

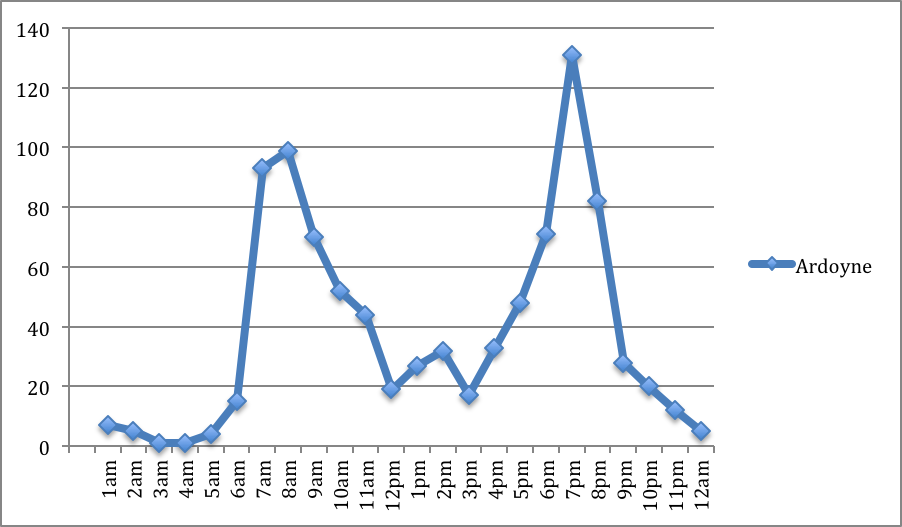

A keyword search, ‘Ardoyne’, was used to identify tweets that referred specifically to the decision to reroute the parade by the Ligoniel Orange lodges in North Belfast. The ‘Ardoyne’ tweets peaked at 7pm on 12 July (see Figure 1). One interpretation of this finding might be that that viewers of ‘flagship’ teatime news programmes such as BBC Newsline and UTV Live, which had provided coverage of the day’s events, had turned to social media to seek out information about the homeward leg of the parade.

Figure 1: Tweets mentioning Ardoyne, 12 July 2014

A critical thematic analysis of all relevant tweets was then conducted in order to analyse how critics and supporters of the Orange Order used Twitter to respond to the rerouting of the Ardoyne parade.

Most peaceful Twelfth in years but little sign of end to Ardoyne impasse

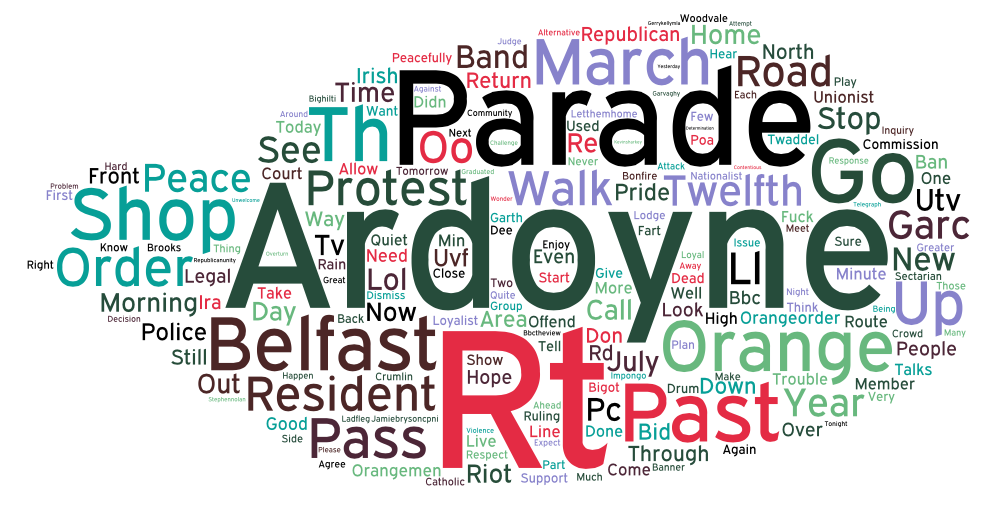

The absence of violence in the contested interface area meant that there was very little for citizens or professional journalists to comment on during this period. Nevertheless, professional journalists were still responsible for the most frequently retweeted content referring to the events in Ardoyne during this period. Analysis of the words most frequently used to characterise the morning parade showed how peaceful it had been (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Most frequently occurring words in Ardoyne sample (11-14 July 2014)

The vast majority of original tweets in the sample expressed support for all those who had contributed to the morning parade passing off without incident. The few politicians who commented on Ardoyne expressed similar sentiments. North Belfast Sinn Fein MLA Gerry Kelly tweeted that it had been the quietest Eleventh night in years and that the morning parade has passed off “without trouble.” However, politicians tended to praise the behaviour of their respective constituents while criticising the intransigence of the ‘other’ community.

A small minority of tweeters blamed the ‘other’ side for the Ardoyne dispute, with little sign of rational debate about how to resolve it. This tended to revolve around crude stereotypes of groups and political leaders, rather than specific individuals, except for a few notable exceptions such as one loyalist woman who was identified as being responsible for sharing a sectarian image on Facebook. Republicans characterised loyalists as a “sectarian hate mob”, lacking the “muscle” to force their way past the Ardoyne shops. Loyalists themselves criticised the Parades Commission and the PSNI for supposedly rewarding the republican violence in July 2012 by rerouting the return parade away from the Ardoyne shops. The rerouted parade was said to be further evidence of republican bigotry and intolerance towards unionist and loyalist culture.

Twitter users move quickly to debunk rumours and misinformation

Rumours in the Ardoyne tweet sample appeared to have a short life span. Loyalists were accused of digitally altering pictures in order to portray GARC and the nationalist residents in a negative light. A picture of one of the protesters that had gathered outside the Ardoyne shops began to circulate on Twitter shortly after 7.30pm on 12 July. The placard being held aloft by the protester contained a mock-up road sign indicating that the Orange Order was not welcome in the area. Visual evidence suggesting that this was a photoshopped image was shared on Twitter within a few minutes of the tweet being posted. The original image showed that the protester was involved in a peaceful Christian protest at the shop fronts. His placard contained the motto “Love Thy Neighbour”, not the anti-Orange Order slogan that had featured in the doctored image. This was corroborated by an image of the same scene taken by BBC NI journalist Kevin Sharkey a few hours earlier and shared on the site.

Loyalists also responded quickly to online rumours suggesting that an image of Oscar Knox, the five year old who had died of a rare form of childhood cancer, had been burnt on an Eleventh night bonfire in Randalstown, County Antrim. A picture supposedly showing the bonfire began to circulate on Twitter late on 11 July, prompting many angry responses from Twitter users. This rumour was quickly refuted and condemned by unionist and loyalists on Twitter. The Randalstown Sons of Ulster Flute band asked people to retweet an image of their Eleventh night bonfire, confirming that no image of Oscar Knox had been burnt and stating that the five year old “was a hero”. One tweet provided a link to the original image of the bonfire that had been taken by photographer Stephen Barnes in July 2013. It was noticeable that the number of tweets referring to the Knox incident sharply declined after this contradictory evidence began to circulate online. As had been seen with the image of the GARC protester, Twitter provided a platform for both sides to correct misinformation and rumours that had the potential to increase the sectarian tensions surrounding the Ardoyne impasse.

Social media as a tool to help defuse sectarian tensions around marches?

Although there was no equivalent of the “crowdsourced newswire” that emerged via NPR editor Andy Carvin’s Twitter account during the ‘Arab Spring,’ Twitter did provide users with an array of information sources courtesy of the citizen and professional journalists who were tweeting their perspectives on events as they unfolded. Citizens were also quick to check the veracity of the user-generated content that was emerging from the scene, such as the photoshopped images that were evident in the sample. While acknowledging that social media has often been used to reinforce divisions between rival communities in Northern Ireland, this study suggested that Twitter may have untapped potential in facilitating modes of communication that help defuse sectarian tensions around the marching season.

For the full report, see ‘Social Media, Parades and Protest’ on the Northern Ireland Community Relations Council Live website

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article originally appeared at our sister site, British Politics and Policy at LSE. It gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Py2sGW

_________________________________

Paul Reilly – University of Leicester

Paul Reilly – University of Leicester

Paul Reilly is Lecturer in Media and Communication, at the University of Leicester. His current research focuses on the role of Web 2.0 technologies in the ongoing processes of conflict transformation in divided societies. His previous research focused on the website strategies adopted by civil and uncivil actors in Northern Ireland and the visibility of terrorist websites on Internet search engines.