Ministerial careers can be notoriously nasty, brutish, and short, with the doctrine of ministerial accountability leading to numerous prematurely ended political careers. But how do European democracies compare? Looking at evidence from seven countries, Jonathan Bright, Holger Doring, and Conor Little show that younger ministers survive longer, right-wing parties are more likely to dump ministers than left-wing ones, and that large coalitions offer greater stability for ministers.

Ministerial careers can be notoriously nasty, brutish, and short, with the doctrine of ministerial accountability leading to numerous prematurely ended political careers. But how do European democracies compare? Looking at evidence from seven countries, Jonathan Bright, Holger Doring, and Conor Little show that younger ministers survive longer, right-wing parties are more likely to dump ministers than left-wing ones, and that large coalitions offer greater stability for ministers.

The recent UK general election surprised everyone by producing a familiar result: a majority government. Once the norm, majority governments are expected to be increasingly rare in the UK as the country transitions to a multi-party system; though it might seem exceptional now, the Lib-Con coalition which ruled until 2015 may come to be remembered as the first of many. With other traditionally majority rule countries such as Spain moving in a similar direction (few expect either the PSOE or PP to be able to govern by themselves after the general election later this year), coalition politics may be set to dominate European democracy for the foreseeable future.

The increasing importance of coalition politics has stimulated a varied literature on the dynamics of coalition stability. Stability is a key issue in democratic politics: increasingly so in the context of current European turbulence. Too little stability and government may be weak and ineffectual, without the time to come to grips with power or enact key legislation. Too much and government may become corrupt and sclerotic, out of touch with the needs of the voters.

Interest in the stability of coalition governments has itself prompted a research agenda on the careers of individual ministers (see here for a good summary), which stems from the realisation that they are not necessarily going to be coterminous with individual governments. Ministers can easily outlast coalitions: for example, a Liberal-Labour government, which appeared a possibility in the months leading up to the UK’s election, would have apparently constituted a significant change in UK politics, but it might also have returned a large number of Liberal ministers to their posts.

However, ministers also face a variety of non-electoral threats to their office: poor performance, scandal, or simply a desire to reshuffle the government may also lead them to being moved on. Furthermore, without being sacked, ministers may be moved around to a new job, perhaps promoted, perhaps given a more minor brief. In short, political turbulence at the party level might disguise significant stability at the ministerial level; or vice versa.

This potential disconnect between party and ministerial politics makes it important to explore the reasons why some ministers are able to remain in power longer than others, something we tackle in a recent research paper in West European Politics. One of the things which has held back the study of ministerial careers is the availability of comparative, cross national data. For the paper, we built a novel dataset covering seven European countries in the period 1945 – 2011 based on the list of ministers maintained by Lars Sonntag, supplemented with data scraped from the Wikipedia pages of ministers. All data was validated manually by the research team. We link these data to portfolio salience scores developed by Druckman and Warwick, which allowed us to build a systematic picture of not only which positions people hold, but how powerful they were.

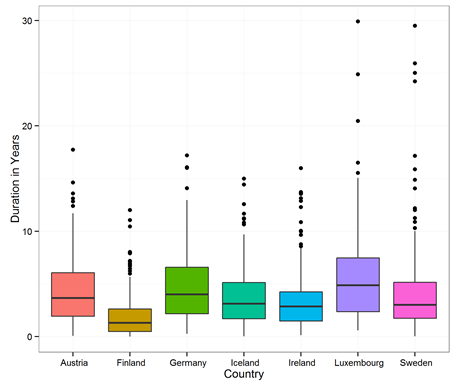

Figure 1: Length of ministerial careers in different European democracies

The dataset constructed provided a number of intriguing possibilities for the study of ministerial careers. The average minister spends 3.6 years in government (see figure 1), though this varied widely between countries: Finnish ministers stuck around for just 1.8 years, while Luxemburgish ministers were typically in power for almost 6 years. Furthermore, while the majority of ministers were in power for these relatively short periods, a select few remained in government for decades, for example during Sweden’s period of stable government following World War Two. These ministers, who remain in their posts as long as monarchs, are positioned to have significant influence on their country.

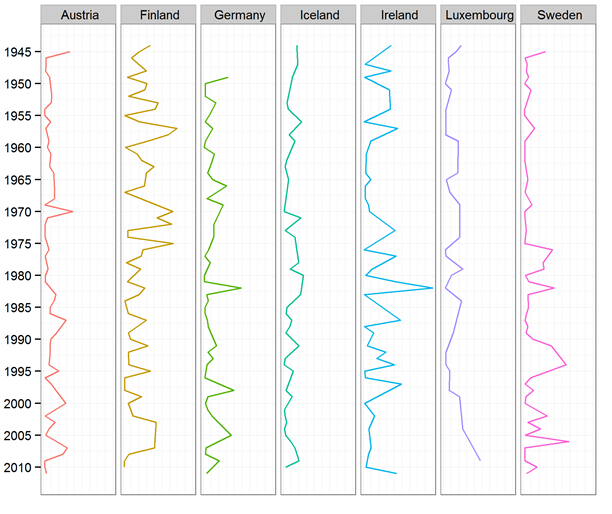

Figure 2: Ministerial power transfer in European democracies over time

As we measure the relative importance of each position, the dataset also allows us to visualise the extent to which power changes hands in different countries at different times (see figure 2). Major shifts in the makeup of government are sometimes described as political “earthquakes”: if that’s the case, this provides a kind of political seismometer. We can see instantly, for example, that countries such as Austria, Iceland and Luxembourg are relatively stable; whereas Finland experiences frequent, major power shifts and Ireland experienced very high turnover during a period of instability in the 1980s.

Finally, the dataset allowed us to explore some analytical questions: why do some ministers stay in power longer than others? We find that younger ministers are more likely to survive for longer, as are ministers in more important positions. We notice different dynamics in different parties, with right wing parties more likely to remove ministers than left wing ones while in government. Women were also more likely to leave their post while their party remained in power, though overall their careers were of comparable length to male ministers. Furthermore, larger coalitions appear to offer greater stability for ministers (even if they are often less stable for governments).

These findings nuance in important ways our understanding of what it means to have a stable government, and the forces that drive stability at the level of the individual minister.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article originally appeared at our partner site, Democratic Audit. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Bob Jagendorf (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1cOY4V5

_________________________________

Jonathan Bright – Oxford Internet Institute

Jonathan Bright – Oxford Internet Institute

Jonathan Bright is a Research Fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute (oii). He specialises in computational and ‘big data’ approaches to the social sciences.

–

Holger Döring – University of Bremen

Holger Döring – University of Bremen

Holger Döring is a lecturer at the Centre for Social Policy Research (ZeS), University of Bremen. He has studied the chain of democratic delegation in the EU by analysing the party composition of EU institutions. His recent work has focused on democratic representation in Western and Central/Eastern Europe.

Conor Little – University of Copenhagen

Conor Little – University of Copenhagen

Conor Little is currently a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Copenhagen.