The UK’s EU referendum is likely to be heavily influenced by the extent to which David Cameron is successful in his attempt to renegotiate the country’s terms of membership. Iain Begg writes that while Cameron’s intention appears to be to gain enough from a renegotiation to win the referendum, he faces a difficult balancing act in keeping other EU governments on side. Should the rest of the EU reach the conclusion that retaining the UK is not worth the price that has to be paid, the country could find itself slowly pushed toward the exit door.

The UK’s EU referendum is likely to be heavily influenced by the extent to which David Cameron is successful in his attempt to renegotiate the country’s terms of membership. Iain Begg writes that while Cameron’s intention appears to be to gain enough from a renegotiation to win the referendum, he faces a difficult balancing act in keeping other EU governments on side. Should the rest of the EU reach the conclusion that retaining the UK is not worth the price that has to be paid, the country could find itself slowly pushed toward the exit door.

There is a presumption that the possibility of the UK leaving the EU (Brexit) is a choice for the British people alone. They will assess the new deal that Cameron is able to achieve and decide whether it is enough to allay concerns about continued membership of the EU.

What this narrative overlooks is that the momentum on the other side of the English Channel is towards deeper integration. It is most visible in the wide-ranging efforts to complete economic and monetary union, but there is also evidence of a desire for more extensive common policies in other areas, such as migration, internal security and justice, or energy policy.

The upshot is that the UK is increasingly the exception to common policies, a stance that is a source of growing irritation in other EU capitals. If that irritation intensifies further, there may come a stage where others say ‘enough is enough’ and start to contemplate pushing the UK out of the EU. As things stand, ‘Brexpulsion’ rather than ‘Brexit’ may appear unlikely, but if the UK seeks ever more exceptions, it could well come on to the agenda.

Push or jump?

Over the years, the UK has been keenest on the economic dimension of integration, especially the single market, and instinctively suspicious of the political dimensions. The prospect of reconciliation between traditional enemies, binding European countries into an ‘ever closer union’, has never really resonated in Britain, so that it is no surprise that exemption from this pledge is one of Britain’s demands. Latterly, however, even the single market has come in for criticism because it is associated with common regulations that many UK businesses find onerous.

In practice, the pitch that David Cameron is making to the rest of the UK contains two very different messages. The first, already prominent in his 2013 Bloomberg speech in which his opening sentence states ‘I want to talk about the future of Europe’, is that a successful EU requires reform, particularly to meet the intensifying competition from emerging markets. He also notes ‘a growing frustration that the EU is seen as something that is done to people rather than acting on their behalf’. There are many in Europe who agree with these sentiments and would support moves to achieve, for example, better regulation. The audience for these demands is EU countries frustrated (for whatever reason) with ‘Brussels’, economic actors who want a more effective, nimble and, often, limited EU, and the national leaders most concerned about Europe in the world, such as the Swedish and Dutch Prime Ministers.

It is the second dimension of Cameron’s case that is more challenging, not least because his principal target audience here is domestic and mainly composed of mild Eurosceptics. He knows that the hard-line Eurosceptics are pretty much a lost cause and will vote ‘no’ regardless of what goodies he brings back from his tour d’Europe. He also faces the rather ironic difficulty that some of the changes he wants will diminish the attractiveness of the EU for staunch pro-Europeans. By seeking, via re-negotiation to change the terms of UK membership of the EU, he is trying to pave the way for the waverers in a referendum to vote ‘yes’. Calls for curbs on EU migrants, more say for national parliaments and protection from Eurozone initiatives that take too little account of non-participating countries speak to this second audience.

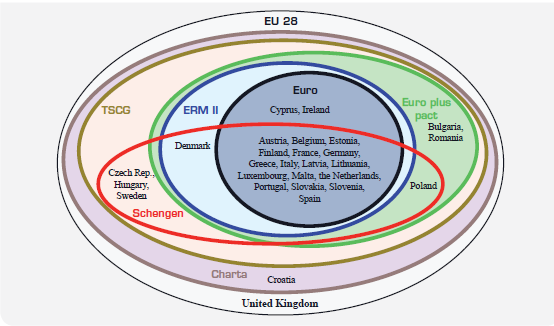

The list of areas that the UK has chosen to shun is substantial and growing, but the number of countries sharing British preferences is, for the most part, shrinking. The most high-profile are the euro, with 19 participants and the likelihood that the number of ‘outs’ will fall further later in this decade; and the Schengen area in which only Ireland and Cyprus may stay with the UK outside within three or four years. The UK opted-out of a raft of justice and home affairs provisions, then restored a minority of them; it has refused to participate in banking union, despite the pre-eminence of the City of London as a global financial centre in Europe; and recently rejected calls to share some of the burden of absorbing the ‘boat people’ crossing the Mediterranean, apparently earning Cameron some choice language from Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi.

What this overview of UK exceptionalism reveals is that although no single dossier is crucial, it is their proliferation that is striking. In each case, there are some other countries that share Britain’s reluctance to participate, but none which seeks so many exceptions. Attempts to construct Venn diagrams show the extent to which the UK is outside the core, as can be seen from the simplified version of a chart constructed by Funda Tekin of the Institut für Europäisches Politik, presented in the figure below.

Figure: Europe: united in diversity

Note: Figure adapted from Differentiated Integration at Work by Funda Tekin.

Reports circulating after the June 2015 European Council suggest that the strategic objective for Cameron is to achieve enough from his ‘renegotiation’ to enable him to advocate and then secure a yes vote in the referendum and, by so doing, to put to bed an issue that has haunted – and often traumatised – his party since the mid-1980s. But he faces a tricky balancing act, as do some of the leaders most sympathetic to his predicament. They have to be aware that defeat for Cameron makes Brexit a virtual certainty, with little chance that a change of heart could be achieved in a second referendum as happened twice in Ireland.

There have already been a number of occasions where a choice between the UK and the wider EU interest has had to be confronted, particularly by the Germans. For example, following the European Parliament elections in May 2014, the UK objected to the imposition of the Parliament’s preferred candidate (the so-called spitzenkandidat) as President of the European Commission. To judge by the briefings at the time, David Cameron clearly thought he had secured the backing of the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, to block Jean-Claude Juncker, only to be swiftly disabused when Merkel realised that there would be significant objections on the grounds of democratic principle, both within Germany and elsewhere. Merkel could have backed Britain and would have influenced many others, but ultimately chose not to, and in the end, only Viktor Orbán of Hungary joined the Cameron camp.

Similarly, noting that concerns about the impact of migrants are prominent in German politics, Cameron thought he would find allies in Berlin in his quest to curb freedom of movement of labour. Again, however, he was firmly rebuffed on the grounds that so fundamental a principle was not, and could not, become negotiable. Nor is his stance on migrants likely to find favour in Warsaw where his Polish counterpart, Ewa Kopacz, recently gave his proposals to curb in-work benefits for migrants a frosty reception.

Three dilemmas will now have to be faced. The first, underlying one, is that the UK is on a quest for shallower integration at a time when, in one way or another, the other Member States, though clearly to differing degrees, are more receptive to a deeper EU, at least in areas such as economic governance. The second dilemma is whether UK antagonism to deepening – even where the UK ostensibly encourages the process, despite insisting on being outside it – has become an obstacle to achieving some of the changes considered necessary to enable the EU overall, and certainly the Eurozone, to function effectively.

The longer-run implications for the EU constitute a third dilemma. Should the UK be regarded as one of a kind, or will further concessions to the UK trigger a series of demands from other Member States for their own exceptions? If so, the shift from a two (or multi) speed model of integration towards the same objectives will be replaced by an à la carte model which many Member States would find unappealing. In resolving each of these dilemmas, the same question crops up: is retaining the UK in the EU worth the price that has to be paid? So far, the answer has been a qualified ‘yes’, albeit with clear signals that unrealistic demands will not be accommodated.

In UK labour law there is a concept of ‘constructive dismissal’ which refers to circumstances in which the employer makes life so unpleasant for the worker – for example by giving them demeaning tasks, or subjecting them to forms of bullying – that the latter quits. Where it is proven in an industrial tribunal, the employer becomes liable for having unfairly dismissed the employee, even though an actual firing did not occur.

This concept may be useful in examining how a Brexpulsion might occur. If the UK repeatedly finds its position on key political or policy issues rebuffed, or is excluded from decisions, it may be the Brits who pull out, but it will be for reasons akin to constructive dismissal. The UK government’s advice to employees who think they have a case for constructive dismissal therefore makes interesting reading:

If you do have a case for constructive dismissal, you should leave your job immediately – your employer may argue that, by staying, you accepted the conduct or treatment.

If the constructive dismissal parallel holds, the implication may well be that the UK should jump out of the EU before being pushed, but there should be no doubt that it would still constitute Brexpulsion, rather than a reasoned choice to exit, because the patience of the UK’s partners will have become exhausted. We are still some way from such a scenario, but the illusion that the forthcoming referendum on Brexit is a choice for the UK voters alone needs to be dispelled. We have to talk about it.

This contribution is an abridged version of a policy analysis published by the Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Number 10/Arron Hoare (Crown Copyright)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1g6qpYX

_________________________________

Iain Begg – LSE

Iain Begg – LSE

Iain Begg is a Professorial Research Fellow at the European Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science, and Senior Fellow on the UK Economic and Social Research Council’s initiative on The UK in a Changing Europe.