In the European Parliament, a ‘rapporteur’ is an MEP appointed to oversee the drafting and presentation of reports. This role is highly important in the Parliament, with rapporteurs being elected to the position by their fellow MEPs. But does the distribution of these appointments favour certain states over others? Steffen Hurka, Michael Kaeding and Lukas Obholzer present findings from a study of the allocation of rapporteurs in the 2009-14 parliament. They find that new member states that joined in the 2004 and 2007 enlargements were underrepresented among rapporteurs and were therefore less able to influence EU legislation than older member states.

In the European Parliament, a ‘rapporteur’ is an MEP appointed to oversee the drafting and presentation of reports. This role is highly important in the Parliament, with rapporteurs being elected to the position by their fellow MEPs. But does the distribution of these appointments favour certain states over others? Steffen Hurka, Michael Kaeding and Lukas Obholzer present findings from a study of the allocation of rapporteurs in the 2009-14 parliament. They find that new member states that joined in the 2004 and 2007 enlargements were underrepresented among rapporteurs and were therefore less able to influence EU legislation than older member states.

In a recent study, we have assessed rapporteurship allocation in the seventh European Parliament (EP, 2009-14). Our research produced surprising and potentially concerning results: We found that Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) from newer Member states remain considerably less likely to act as rapporteurs even during the second term after the Eastern enlargement (2009-14). Most importantly, this trend also holds for shadow reports, which are a stepping stone toward lead rapporteurships and easier to obtain.

The reason why this is highly relevant is simple: The European Parliament’s influence in the decision-making process of the European Union is steadily growing. Among MEPs, the rapporteur is the “primary legislator”. Rapporteurs and their “shadows” draft the legislature’s opinion and negotiate on its behalf with the European Commission (Commission) and Council of Ministers (Council).

As a consequence, they are the linchpin of intra and inter-institutional decision-making and have important procedural privileges. As the importance of rapporteurs has increased, they have been more tightly controlled by shadow rapporteurs from competing party groups. ‘Shadows’ follow the progress of a file through committee and plenary, and can for instance join the rapporteur in closed-door trilogues with the Commission and Council.

During the period since the admission of 13 new member states to the European Union starting in 2004, previous research has found clear evidence that MEPs from new member states have been underrepresented in these key posts. This might have been due to a ‘learning phase’: that is MEPs from the new member states were expected to need some time to get used to the proceedings of the EP in order to get into influential positions. Hence, we did not expect any systematic difference between MEPs from old and newer member states in rapporteurship allocation in the seventh European Parliament – but our study suggests the opposite.

Report allocation in the EP ten years later: still no level playing field

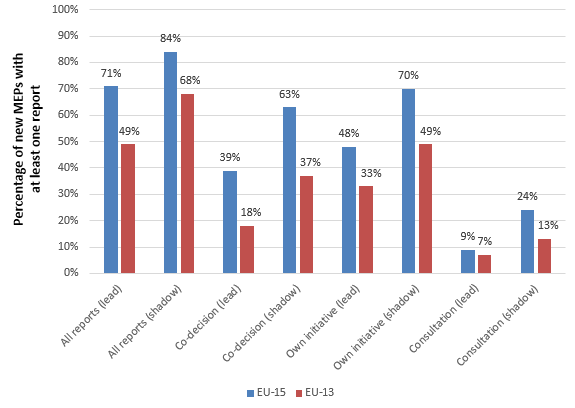

We re-examined the original argument and investigated the allocation of rapporteurships and shadow rapporteurships in the 2009-14 term (EP7) to MEPs from one of the Member States that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007. Our dataset includes the allocation of 2,161 reports (see Figure 1) and 6,589 shadow reports to 851 MEPs, i.e. the population of reports retrievable from the website of the EP after the last plenary session in April 2014. The results show a clear deficit in rapporteurships for MEPs from the new Member States despite the fact that the distribution of reports is highly proportional to the party groups’ seat shares in the plenary. For shadow reports, our results suggest that underrepresentation is particularly pronounced for politically important co-decision files.

Figure 1: Report allocation across party groups and procedures (EP7)

Note: For more information on the calculations, see the authors’ accompanying journal article. For more information on the groups, see: European People’s Party (EPP); Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D); Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE); The Greens–European Free Alliance (Greens–EFA); European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR); European United Left–Nordic Green Left (EUL/GUE-NGL); Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD – formerly EFD). NI refers to MEPs that are not members of any group.

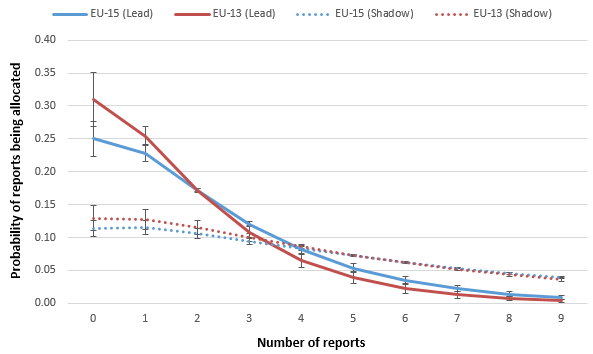

Figure 2: Report allocation of newcomer MEPs (percentage of MEPs with at least one report)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article.

In a nutshell, Figure 2 shows that the percentage of newcomer MEPs who obtained at least one report is consistently higher among MEPs from the EU-15 than for those from the EU-13. Specifically, the difference between the two groups amounts to 22 percentage points for all reports and 21 percentage points for co-decision reports. Accordingly, the under-performance of MEPs from the accession states is not merely a result of a lack of political experience. If this were the case, their rates of report allocation would be similar to the rates of newcomer MEPs from the EU-15.

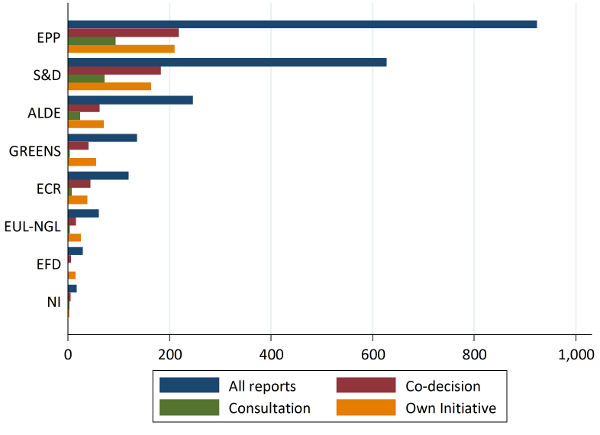

If we model the counts of allocated reports and derive predicted probabilities, an interesting picture emerges, shown in Figure 3 below. For all shadow reports, no significant difference between the two groups of newcomer MEPs can be discerned, although our models show that MEPs from the accession states are in general significantly underrepresented for co-decision shadow reports (see the accompanying paper for more details). For all lead rapporteurships, the probability of receiving no report at all is clearly higher for newcomer MEPs from the accession states than for their colleagues from the EU15. Interestingly, newcomer MEPs from the accession states are even more likely to draft exactly one report, but their fortunes are reversed for two or more reports, leading to the aggregate pattern of underrepresentation.

Figure 3: Report allocation: predicted probabilities for newcomer MEPs (all reports)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article.

Furthermore, our study revealed additional information about the allocation of rapporteurships: Chairmen and chairwomen received more reports than regular or substitute committee members, due to the fact that they are responsible for the drafting of reports which are not acquired by any political group. The results also underscore previous findings on the importance of attendance rates for the allocation of reports. Party groups reward active MEPs with influential positions in the legislative process. Also an MEP’s seniority is relevant for his or her chances to obtain rapporteurships, which corroborates recent findings.

Variation across different types of legislative procedures

Our results suggest, however, that the relationship does not hold across all types of legislative procedures. More senior MEPs are especially active in the drafting of consultation reports, which raises the suspicion that experience (and perhaps good contacts) are particularly relevant if the EP does not have any clear-cut procedural power. Our results do not confirm a gender discrimination effect in the report allocation process. Female MEPs were neither more nor less likely to obtain reports than their male colleagues across all legislative procedures. Finally, we find that MEPs whose home countries held the Council Presidency were underrepresented in the allocation of co-decision reports. However, this finding does not hold for the other legislative procedures.

This raises important questions: chiefly, why has the under-representation of MEPs from formerly new Member States in the post of rapporteur become a structural feature of the EP? There are three main readings of the unexpected results: Firstly, the incentive set of this group of MEPs may differ from that of MEPs from older member states, making them less willing to take on the workload that accrues to a (shadow) rapporteur. Secondly, MEPs from these countries may adopt different methods for effective representation of their constituents’ interests and therefore have distinct skill sets. As a consequence, they may be better suited for other positions or activities than those of the rapporteur. Thirdly, there might be a systematic bias in the rapporteurship allocation process, disadvantaging MEPs from newer member states. As of now, it is an open question which of these arguments has the most explanatory power.

In any case, MEPs from newer Member States are less able to influence European legislation as a result of their absence from influential rapporteur positions. This might adversely affect the legitimacy of European integration in these countries. Therefore, MEPs from the newer member states may want to thrust themselves more actively into the competition for rapporteurships during the 2014-19 legislative term. National parties might want to optimise their candidate selection in order to ascertain that a share of their MEPs are committed to a longer term career at the European level.

For more information on the study, see the authors’ article in the Journal of Common Market Studies

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: © European Union 2014 – European Parliament (CC-BY-SA-ND-NC-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1W3bhwo

_________________________________

Steffen Hurka – University of Munich

Steffen Hurka – University of Munich

Steffen Hurka is a post-doctoral researcher at the Geschwister Scholl Institute of Political Science at the University of Munich (LMU). His main research interests include European Union politics in general and the legislative organization of the European Parliament in particular. Related articles can be found in the Journal of European Public Policy, European Union Politics and the Journal of Common Market Studies. The other main focus of his studies is on the politics of morality policy. Together with Christoph Knill and Christian Adam, he recently co-edited the book “On the Road to Permissiveness? Change and Convergence of Moral Regulation in Europe” with Oxford University Press.

Michael Kaeding – University of Duisburg-Essen

Michael Kaeding – University of Duisburg-Essen

Michael Kaeding is Professor of European Integration and European Union Politics and ad personam Jean Monnet Chair at the Institute for Political Science at the University of Duisburg-Essen, Visiting Professor at the College of Europe (CoE) in Bruges, and Visiting Fellow at the European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA), the Netherlands. In addition, he is associated editor of the Journal of European Integration and author of articles and books on topics such as the social selectivity in voter turnout across multi-level systems, European elections, the micromanagement of EU institutions, delegated and implementing acts, and the implementation of EU rules, norms and values across Europe.

Lukas Obholzer – LSE

Lukas Obholzer – LSE

Lukas Obholzer is Fellow in European Politics at the Government Department at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He holds a PhD from the LSE’s European Institute. His research focuses on bicameral decision-making, legislative organisation and European Union politics.