Portugal was one of the countries hardest hit by the Eurozone crisis, yet in contrast to countries such as Greece and Spain, there has been no sharp rise in support for radical left or anti-establishment parties. Ahead of the next Portuguese legislative election on 4 October, Alexandre Afonso writes that there are a number of possible reasons why a surge in radical-left support has failed to materialise, including Portugal’s pre-crisis economic trajectory, and the fact that the centre-left Socialist Party has managed to escape taking the blame for the country’s economic situation.

Portugal was one of the countries hardest hit by the Eurozone crisis, yet in contrast to countries such as Greece and Spain, there has been no sharp rise in support for radical left or anti-establishment parties. Ahead of the next Portuguese legislative election on 4 October, Alexandre Afonso writes that there are a number of possible reasons why a surge in radical-left support has failed to materialise, including Portugal’s pre-crisis economic trajectory, and the fact that the centre-left Socialist Party has managed to escape taking the blame for the country’s economic situation.

The next Portuguese legislative election is scheduled for 4 October, and compared to the fierce battles fought between establishment parties and anti-austerity challengers in other countries, it looks fairly sedate. The latest polls indicate a close call between the PSD/CDS-PP coalition (currently in power) and the Socialist Party. These are the parties that have alternated in power for the last 30 years. Among the Southern European countries which have been severely hit by the Eurozone crisis, Portugal is the only one where the party system has not undergone significant change.

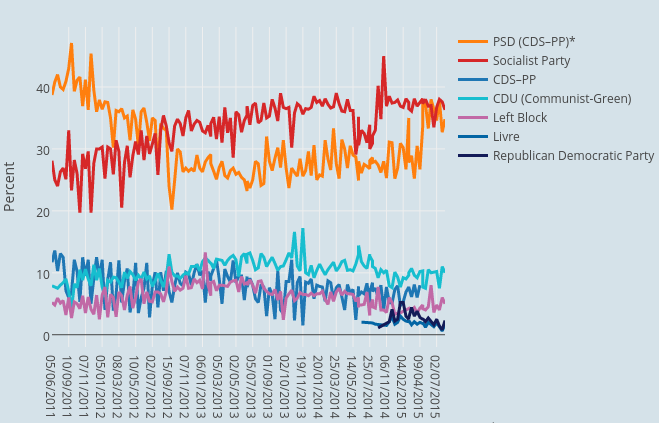

In the context of significant cuts to social programmes and public sector wages, the Socialists have been leading the polls for most of the current parliament, but the decision of the two right-wing parties in power to run together have put them back in the race. It is now unclear whether any of them will be able to secure a majority in Parliament, but their electoral support has remained fairly stable in spite of a fairly dire economic situation.

Some timid signs of recovery are visible, but high unemployment, low productivity and a huge demographic problem (low fertility and high emigration) still constitute major stumbling blocks on the path out of the crisis. In this context, what really sets Portugal apart is the ability of the centre parties to maintain fairly high levels of electoral support and contain the left-wing surge observed elsewhere.

While Syriza and Podemos have polled at 35 per cent and 20 per cent respectively, the Left Bloc (their Portuguese equivalent) has hovered around 5 per cent, with the Communist Party doing somewhat better at 10 per cent. Meanwhile, the Spanish centre-left PSOE had fallen down to 20 per cent in July 2015, while PASOK had collapsed below 5 per cent. The Portuguese Socialists, in contrast, have maintained support around 35 per cent.

Figure 1: Polling figures for Portuguese parties (2011-2015)

Note: The PSD figures include CDS-PP as of April 2015. For more information on the parties see: Social Democratic Party (PSD); CDS – People’s Party (CDS-PP); Socialist Party (PS); Democratic Unitarian Coalition (CDU – which is a coalition between the Portuguese Communist Party and the Ecologist Party); Left Bloc; FREE/Time to Move Forward (Livre); Republican Democratic Party (PDR).

In Greece and Spain, Syriza and Podemos have capitalised on popular opposition to austerity measures and high unemployment. They have become serious challengers to traditional centre-left parties, who have had a very hard time reconciling left-wing ideals with EU-backed austerity. In fact, in Greece PASOK, once the largest and best organised Greek party, has been reduced to a marginal political force after backing cuts that severely hit its electorate.

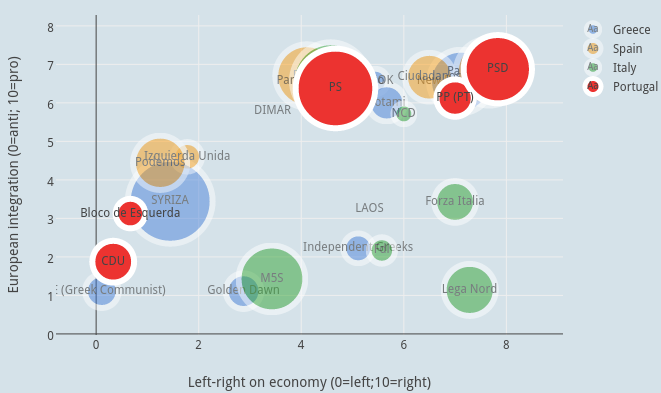

Figure 2 shows indeed that in Greece, Spain and Portugal, there is a clear relationship between the left-right position of parties and their position on European integration, the latter being associated with cuts in spending and the retrenchment of the state. However, the centre of gravity of the party systems differ: the Eurosceptic left (in Greece and Spain) and the Eurosceptic right (in Italy) are strong contenders to the mainstream parties in Italy, Spain and Greece, while they remain relatively small in Portugal. How can we explain this?

Figure 2: Southern European political parties by ideological placement

Note: Data from Chapel Hill Expert Survey 2014. Bubble size corresponds to electoral strength.

There are a number of possible reasons for why Portugal hasn’t seen the kind of left-wing surge that other comparable countries have undergone in the last couple of years. The first may have to do with the economic trajectory of these different countries: an economic boom in the pre-crisis period allowed for clientelistic strategies by major parties in Greece and in Spain, which had to be stopped suddenly when the crisis hit. Voters sanctioned these swings severely. In contrast, Portugal has faced a period of long stagnation since its entry in the Eurozone: change was not as sudden, and austerity had started much earlier.

Second, in contrast to PASOK, who had to implement harsh austerity measures in a coalition with New Democracy, the Portuguese Socialists have managed to escape the blame by leaving power when the country was bailed out in 2011. A change of leadership also made it possible for the party to dissociate itself from its period in office. The new leader is now Antonio Costa, the popular former mayor of Lisbon, while the former prime minister José Socrates now sits in jail under corruption charges.

The third reason is the small political space left by the Communist party for a left-wing challenger. In spite of its modest size and fairly old-school discourse, it has traditionally been well organised and enjoys a trustful electorate, making it difficult for a new political force to mobilise voters on that side of the political spectrum.

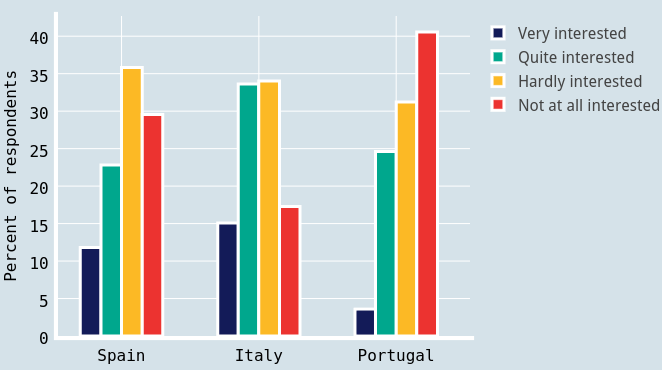

Figure 3: Interest in politics in Italy, Portugal and Spain (2014)

Note: Figures from European Social Survey Wave 6 (2014).

Finally, a major factor that underpins the absence of a populist surge in Portugal is the generally low degree of politicisation of voters. Data from the most recent wave of the European Social Survey reveals that Portugal had higher proportions of voters who had no interest in politics (Figure 3) than Spain and Italy (we do not have data for Greece). However, trust in politicians was at similarly abysmal levels. We can hypothesise that unhappy but politicised voters will choose challenger parties (voice), while unhappy but apathetic voters will abstain (exit). Considering very high levels of abstention (and emigration), it is this second strategy that seems to prevail in Portugal.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: K. H. Reichert (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Nz7lRi

_________________________________

Alexandre Afonso – Leiden University

Alexandre Afonso – Leiden University

Alexandre Afonso is an Assistant Professor at the University of Leiden, Netherlands. His research interests are labour market and austerity reforms in Southern Europe, the role of populist right-wing parties in welfare reforms, and the political economy of immigration. He is on Twitter @alexandreafonso

Very interesting analysis indeed!

Muito interessante! A questao que se poe e.. porque? Porque e que os portugueses sao tao pouco interessados na politica?

O português médio tem um nível relativamente baixo de escolaridade e por isso não percebe muito do que lhe dizem os políticos, tendo a noção que pouco ou nada pode ser feito para mudar a situação actual. Basicamente é isto: “Eu não sei muito bem do que estás aí a falar, mas és tu que mandas e por isso tu é que sabes!”

Pior que isto é também a noção que os políticos são todos iguais e que é complicado fazer-se o que quer que seja porque o poder é extremamente clientelista e tem muitos amigos para satisfazer, o que conduz à ideia de que raramente sobra alguma coisa para o povo e faça-se o que se fizer, os beneficiados serão sempre os mesmos. Ora, isto conduz ao desinteresse porque não se vêem grandes resultados práticos.

O que a mim me preocupa, daquilo que vejo entre aqueles que têm um nível de escolaridade elevado, é que há muita gente a quem não foi incutido o interesse pela política e que não questionam o que lhes é imposto, tomando-o como um dado adquirido, tendo a noção, que receberam dos seus pais, de que pouco ou nada se pode fazer para mudar a situação actual e que isto só lá vai com uma revolução.

Conheço várias pessoas, jovens e com pelo menos uma licenciatura, que não votam nas eleições porque se elegem sempre os mesmos e que dizem que não vale a pena votar num partido mais pequeno para aumentar a possibilidade de conseguir um assento parlamentar porque no final isso não vai dar em nada e então vale mais fazer alguma coisa mais interessante no dia das eleições. E isto dá jeito tanto ao PSD/CDS como ao PS, porque havendo um nível alto de abstenção é mais fácil conseguirem mobilizar as suas hostes, que votam numa cor política em vez de votarem em propostas credíveis, para ganhar as eleições, uma vez que se aumenta em proporção o nº de votos garantidos relativamente aos votos totais. Isto aliado ao apelo ao voto útil, que diz “votem em mim que tenho mais hipóteses de ganhar do que aquele partido pequeno com o qual vocês concordam mais”, ajuda também a perpetuar a situação, uma vez que desvia votos dos partidos mais pequenos, concentrando-os nos partidos maiores, criando uma situação bipartidária como a que se vê em Portugal que vai acabar por ajudar a perpetuar ainda mais o problema.

Este post no blog do Alexandre relaciona o nível de escolaridade com o interesse na política. O 1º gráfico a mim chocou-me um pouco:

http://alexandreafonso.me/2015/09/15/education-levels-an-interest-in-politics-the-portuguese-outlier/?utm_content=buffer49035&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer

Portuguese workers like many in Europe see no alternative. They are still blinded by the TINA effect of the 1990’s. TINA means; There Is No Alternative, thanks to social democratic and stalinist betrayal, many still believe this. Socialism is not seen as a alternative, but as a failed system. Thanks to massive neoliberal propaganda from both the right-wing Social-Democratic Party and pseudo-leftist; Socialist Party, the two biggest bourgeois parties remain popular. But the more radical left is also to blame. The Left Block has not organized itself around a socialist program and even called for a vote on PS candidates. Communist voters remain loyal to their party, even if the PCP is still very much based on stalinism.

Is there data regarding age or gender? It would be interesting to see if young people are more or less interested in politics.