Anna Triandafyllidou writes on the key measures that are required to help manage the migration crisis, outlining a four-point plan. She argues that EU governments need to broaden their focus beyond the Mediterranean, recognise the mixed motivations that underpin migration, acknowledge the regional realities within individual countries, and better understand the booming smuggling business that facilitates migration routes.

The whole of Europe has been moved by the picture of three year old Alan Kurdi who drowned along with his five year old brother and their mother while trying to cross from Bodrum in Turkey to the Greek island of Kos on 1 September. It was as if Alan has suddenly given a wakeup call to governments and international organisations even though the Syrian refugee crisis has been evolving for well over three years now. Indeed before Greek authorities despaired at the arrival of over 150,000 refugees in the first 7 months of 2015, it had been Italy with its Mare Nostrum operation that had borne the brunt of arrivals both from sub Saharan Africa and the Middle East.

It was probably a “death foretold” before Syrian refugees would be driven out of the Middle East region, where they had found temporary refuge in neighbouring countries (Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan) in the hope of soon returning home. As the war continues and nothing is left but devastation, families gather their resources, and with the help of relatives already living in Europe or North America, try to move on to safe and prosperous countries where they hope they can build a future for themselves and their children.

This is a critical moment for Europe and the international community: both because the emergency has escalated and because European citizens have mobilised in a spectacular expression of solidarity and compassion. As a woman from Munich interviewed on television recently put it: “We have so much. We can share some of it with these people”. At the same time, local authorities and journalists warn that citizens distinguish between refugees that are welcome and considered as deserving assistance, and economic migrants in search of better life prospects that should be discouraged from arriving undocumented and should actually be returned as soon as possible to their own countries.

The Syrian crisis is one of the many expressions of a radically changing landscape in the field of international migration and asylum. There are epochal changes taking place, some of which have been noticed by politicians and policy makers, others which are slowly emerging mainly before the eyes of researchers and experts digging in the field. It is therefore worth summarising these changes and suggesting some policy actions that the EU must consider in this new geopolitical and socio-economic context.

Broadening our Mediterranean focus

First, flows of irregular migrants and asylum seekers are growing, with the Mediterranean sea being the main area of transit into the EU, as the figure below shows. Nonetheless things should be put into perspective.

Figure: Migrant and refugee routes in the Mediterranean

Source: Frontex

Major migration and asylum seeking flows are intra-regional, taking place within Africa or Asia. For instance, half a million Somalis live in Kenya in refugee camps while many Eritreans find refuge in neighbouring Ethiopia. Similarly, millions of Afghans live in Pakistan and millions of Syrians found refuge in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. So we should avoid being extremely Eurocentric or West-centric about current population flows.

Recognising the mixed motivations behind migration

Second, rather than speaking of mixed flows, notably of pathways and irregular border crossings attempted by both people in need of international protection and economic migrants, we are now speaking of mixed motivations. There is a growing awareness that people leaving developing countries in West/East Africa or Asia do so for a number of reasons. For some, like Syrians but also Afghans, Sudanese and Eritreans, the main driver is insecurity and fearing for their lives. For others, such as Iraqis, Pakistanis, Nigerians, Ethiopians and Malians, it is a combination of poverty and the lack of hope for a better life, along with insecurity, absence of the rule of law, and environmental degradation that makes livelihoods increasingly uncertain.

Yet for others, including Bangladeshis, Indians, Moroccans and Tunisians, the main driver is an aspiration for better life prospects. The current context thus requires a new codification, moving away from watertight distinctions between asylum seekers and economic migrants. Not only our distinctions should incorporate an understanding that motivations for migration are nuanced and mixed; we can at best decide what has tipped the balance over leaving vs staying and base our decision for international protection on that turning point, rather than an overall assessment of the migrant/refugee’s situation in their home country.

Acknowledging regional realities

Third, it should be noted that rather than speaking of unsafe vs safe countries which can or cannot produce refugees, we should pay special attention to specific regions within these countries and/or specific ethnic groups. This is typically the case today of Nigerians leaving the northeast of Nigeria, for instance, where fundamentalist groups like Boko Haram are spreading terror among the population, or of the Rohingya, an ethnic minority that lives between Myanmar and Thailand and has been evicted from its homeland territory in the former but has found no sustainable refuge in the latter.

Understanding the booming smuggling business

Finally, while smuggling networks have been present in some form or other in irregular migration routes in the past, they have acquired a new level of sophistication. Put simply their business has boomed in the last few years particularly in the Mediterranean. Having said this, the cooperation between criminal networks and local communities (and even specific ethnic groups in different regions of Africa for instance) is so close and the two aspects of the phenomenon – the criminal aspect and the local rootedness aspect – are so intertwined that we cannot talk of the one without considering the other.

This is an issue that often escapes the attention of politicians and the media who conceive of the migrant smuggling networks in pure criminal activity terms. What is even more important is to recognise that smuggling is conceived of as a service by both migrants and smugglers. It is a give and take relationship. The migration policies of the transit and destination countries are simply hurdles to overcome and the smugglers make that possible, upon receipt of substantial amounts of money.

What happens next?

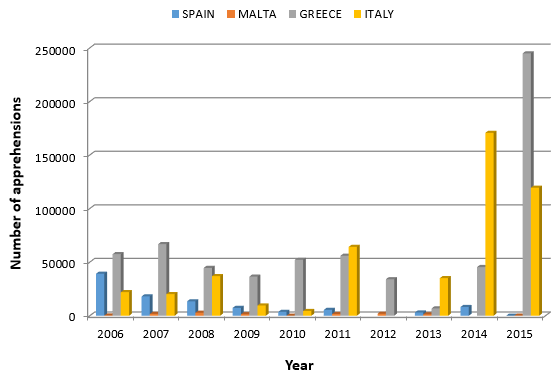

It would be unwise to make predictions about the numbers of refugees still to arrive from Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia and Eritrea. Indeed numbers this year have overturned predictions with Italy receiving approximately 100,000 people so far (from a range of sub Saharan African and Asian countries, with no nationality accounting for over 13 per cent of the total) while Greece has surpassed most predictions with over 250,000 arrivals, of which 60 per cent are Syrians and 25 per cent are Afghans. The chart below gives some indication of the problem being faced in southern European states.

Chart: Total apprehensions at southern European sea borders (2006-15)

Note: The source for the chart is Triandafyllidou, A. (2015) Le trafic de migrants en Méditerranée : réseaux anciens et nouvelles tendances, in Hélène Thiollet, Camille Schmoll, Catherine Wihtol de Wenden (eds) Les Migrations en Mediterrannée. Paris: Editions CNRS, in press. Data are taken from different sources as documented in the publication and have been updated to the latest data provided by national authorities, Frontex, Eurostat and UNHCR.

However our knowledge from previous years, as well as the most recent peak, allows us to envisage what we should expect in the coming months and years. Flows will continue as the Middle East conflict develops and the UNHCR does not even have the necessary financial resources to face a hunger and shelter crisis in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey as well as in Kenya and other places.

There is a need for an emergency and a medium term plan. The emergency plan has partly been worked out by EU authorities (with quotas for distributing 120,000 refugees on top of the 32,000 decided last spring) among the EU member states taking into account the size of the country, its financial and institutional capacity and the number of asylum seekers already hosted. Consensus and peer pressure are mounting in the EU for the reluctant countries (mainly the Czech Republic and Poland along with smaller Central Eastern European member states) to accept the quotas as mandatory.

In addition there will be an assessment of Western Balkan states and Turkey as safe countries so that asylum seekers from those are returned. While this is a necessary assessment, caution should be taken not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Turkey may not be a safe place for Kurds, while other minorities like Albanian Roma may face dire discrimination and inhumane conditions in Kosovo. So exceptions should be made for specific ethnic groups and communities or specific regions in those countries.

The relocation plan now being decided at the EU level should be brought upwards to the UN level, asking for the international community and particularly for the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand to participate in the plan as their share in the refugee resettlement pie has been tiny so far. Arab countries could also be asked to participate. The example of the Indochinese refugee resettlement plan in the 1980s can serve as a good example. And Europe can indeed lead the way.

In the medium term it is clear that at the EU level the Dublin system no longer holds. The first safe country of arrival principle cannot face today’s challenges. What we need is a flexible and practical quota system. There have been interesting proposals voiced by NGOs and experts, such as fair reception quotas and tradable market quotas, in recent years. Tradable market quotas would allow for countries to pay to receive less refugees, in a similar vein to CO2 emission quotas.

However there are reasons to doubt whether tradable quotas are appropriate for refugees. What would happen if Germany or France decided to pay themselves out of the relocation scheme? What would be the political implications at the EU level and what would be the practical implications for the first arrival countries? Instead, the mechanism should be based on the size of a state’s population, its GDP, and the numbers of refugees already present, with some financial and technical assistance being provided by the EU, particularly the European Asylum Support Office (EASO), in organising reception and integration procedures. In this respect the EASO should see its mission radically upgraded and expanded to include more operational support and a decisive role in facing emergencies, as well as building long term institutional capacity for asylum policy and practice.

Last but not least, the war on smuggling (and the related struggle against human trafficking) is a long term one that can best be fought through intelligence and international cooperation. Here the cooperation of the transit countries is essential, but hard to achieve. Oftentimes these are countries that are lawless (Libya), divided (Sudan), very poor (Mali) or unable more than unwilling to cooperate, as corruption is rife and authorities, particularly border guards, collide with smuggling networks. Thus this is an uphill road and EU governments should be frank with their citizens: much like the war on drugs, it takes time and the outcome is dubious as long as local populations live below the poverty line.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1OldNuK

_________________________________

Anna Triandafyllidou – European University Institute

Anna Triandafyllidou – European University Institute

Anna Triandafyllidou is Professor at the Global Governance Programme of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS) at the European University Institute.

Sooner rather than later the rest of the EU will come to see that David Cameron was right & Merkel was wrong. These migrants need to be managed on the ground near to their home country so they can easily return post the conflict & rebuild their societies. Merkel has taken on the laws of physics by suggesting there is no limit to the numbers that Germany can take, she has kicked down the Hoover Dam & expected a steady stream to emerge not the inevitable raging torrent. She is either very stupid or deliberately forcing her agenda or neutralising nationhood within the EU by diluting the populations of the member states. She has trapped migrants inside countries that neither want or have the means to care for them. She may as well have deposited them in the Sahara desert.