David Cameron has sent a letter to the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, outlining the key elements that he will seek in a renegotiation of the UK’s EU membership. As Valentin Kreilinger writes, one of Cameron’s demands is to strengthen the role of national parliaments in the EU’s legislative process, with the provision of a so called ‘red card’ mechanism that would allow groups of parliaments to effectively veto new proposals. He argues that this system would be likely to create more problems than it would solve and could actively work against the UK’s interests by preventing the liberalisation of Europe’s services sector and reforms aimed at boosting competitiveness.

David Cameron has sent a letter to the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, outlining the key elements that he will seek in a renegotiation of the UK’s EU membership. As Valentin Kreilinger writes, one of Cameron’s demands is to strengthen the role of national parliaments in the EU’s legislative process, with the provision of a so called ‘red card’ mechanism that would allow groups of parliaments to effectively veto new proposals. He argues that this system would be likely to create more problems than it would solve and could actively work against the UK’s interests by preventing the liberalisation of Europe’s services sector and reforms aimed at boosting competitiveness.

Strengthening the role of national parliaments is a key idea of UK Prime Minister David Cameron and figures among the priorities for EU reform in his letter to the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk. In his Bloomberg speech on 23 January 2013, the Prime Minister had already said, “We need to have a bigger and more significant role for national parliaments”. He is now suggesting a system that would give groups of national parliaments the power to stop EU laws, i.e. to show a “red card”.

The idea builds upon existing mechanisms – the “yellow card” and “orange card” – which entered into force with the Lisbon Treaty in 2009. In the so called early warning mechanism, a national parliament can currently send a reasoned opinion to the European Commission in case of subsidiarity concerns about a legislative proposal. If one third of national parliaments think that a particular legislative matter should better be regulated at the national level (and not the EU level), the threshold for a “yellow card” is reached. Then the Commission must decide whether it amends, withdraws or maintains the proposal, but any decision must be justified. Since the Lisbon Treaty added the mechanism for subsidiarity control, it has only been triggered twice.

The main risk that comes with the current system is ineffectiveness, because the threshold is difficult to reach within the given timeframe of eight weeks and because there is no obligation for the Commission to take concerns into account and withdraw the legislative proposal when a “yellow card” is triggered. Only if more than half of national parliaments raise subsidiarity concerns is the threshold for an “orange card” reached. In this case, a qualified majority in the Council or a simple majority in the European Parliament is sufficient to force the Commission to withdraw its proposal. This has not happened yet.

The introduction of a “red card” mechanism would significantly alter the constitutional equilibrium in the EU and transform national parliaments into a collective veto player that could block the European Commission’s legislative initiatives. The Lisbon Treaty’s Article 12 TEU and Protocol No. 1 on the role of national parliaments as well as Protocol No. 2 on subsidiarity do not provide a sufficient legal basis for a “red card” which would give national parliaments binding veto power. Some Eurosceptic MPs in the House of Commons even demand veto power for each national parliament. This could bring the entire EU legislative process to a standstill, undermining the integration project and potentially even killing it off altogether.

Both the European Commission and the European Parliament perceive a “red card” as a challenge to their prerogatives and are opposed to the idea. Many supporters of a stronger role for national parliaments, such as the House of Lords, prefer a so-called “green card” mechanism under which national parliaments seek to improve the “political dialogue” with the European Commission about (legislative) initiatives.

A survey among European affairs committees that was prepared for a working group meeting in Luxembourg on 30 October 2015 confirms this. Each of three slightly different ideas for the “green card” mechanisms to be able to send proposals to the European Commission is supported by a significant number of the 41 national parliaments and chambers in the EU. There are 22 national parliaments in favour of submitting new legislative initiatives, 20 in favour of proposing amendments to existing legal texts, and 18 in favour of suggesting the withdrawal of existing laws – the latter idea cannot be interpreted as supporting a “red card”, since the “green card” is a proactive, non-binding instrument for involving national parliaments on the basis of existing treaty provisions. The “green card” would not create a collective veto player and would more loosely build upon the “yellow card” mechanism.

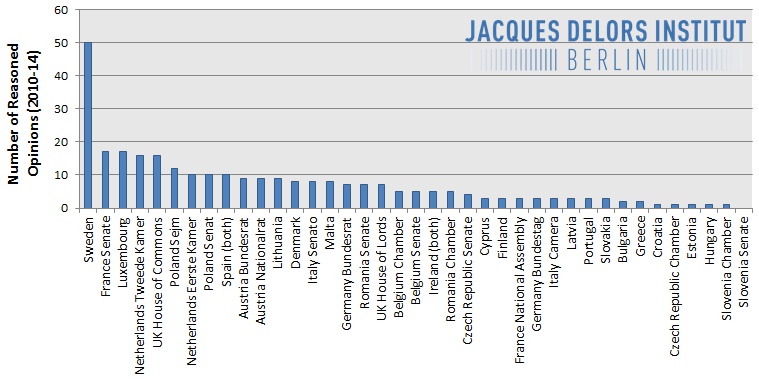

The existing early warning mechanism only allows national parliaments to block EU integration. False “red card” pragmatism – the notion that “if they insist, let’s give them another gadget” – would merely duplicate the current system with all of its shortcomings. In this sense it would do more harm than good to strengthen the role of national parliaments in the EU. The activity of national parliaments in the early warning mechanism varies substantially. On average national parliaments send 1.29 reasoned opinions per year. From 2010 to 2014, the Swedish Riksdag submitted 50 reasoned opinions while the parliaments of Estonia, Hungary and Slovenia each only sent one reasoned opinion to Brussels. This is illustrated in the chart below.

Chart: Number of reasoned opinions issued by national parliaments between 2010 and 2014 (click to enlarge)

Note: Data is from Mastenbroek et al. (2014), Engaging with Europe, 2nd ed., Nijmegen 2014, 110-112 [for 2010-2013]; European Commission (2015), Annex to the Annual Report 2014 on subsidiarity and proportionality, COM(2015) 315 final [for 2014].

In the run-up to the UK referendum, contradictions within the UK’s EU policy and its parliamentary control in Westminster are appearing more clearly. David Cameron has set his hopes on strengthening all 28 national parliaments and transforming them into a powerful collective actor at the EU level, rather than extending parliamentary control exercised by MPs in the House of Commons. However, Britain is an example where a parliament often does not live up to its primary role in EU politics – holding government to account. It seems plausible that the British Prime Minister is worried about his own Eurosceptic Tory MPs and thus resists such calls.

The introduction of a “red card” would also contradict the British agenda for strengthening European competitiveness that includes liberalising the services sector. As stated by Professor Simon Hix at a hearing before the European Scrutiny Committee of the House of Commons, the question arises whether the UK government would in such cases really want to have veto power attributed, for example, to the French National Assembly. The possibility of a “red card” would significantly impede reforms in the field of the internal market, in which the Council of Ministers votes by a qualified majority, and it would ultimately prevent change.

Instead of a bigger house of cards with a new “red card”, the EU institutions and the other Member States should concentrate their efforts on improving the current system. The Commission could promise to consider a yellow card more seriously – or, alternatively, the Council or European Parliament could make a political commitment to drop a Commission proposal if national parliaments oppose it – and the eight-week timeframe could be extended or interpreted in a slightly more flexible way.

In addition, cooperation between parliaments in the early warning mechanism could become stronger. If one national parliament knew beforehand which dossiers other parliaments were examining closely on the basis of possible subsidiarity concerns, this might considerably help efforts to reach the required threshold. The current information flows are often insufficient: MPs should cooperate and exchange more with their counterparts from other countries.

As with his other demands for EU reform, David Cameron will undoubtedly experience difficulties in securing support from other EU states. A binding “red card” mechanism will almost certainly find little backing and cannot be realised without changing the EU’s Treaty framework. Thus the actual result of the negotiations between the EU and its awkward partner will depend on the extent to which the 27 other EU Member States are willing to let the British Prime Minister sell the agreement (that they will most likely reach at some point in 2016 and that will not require immediate treaty change) as a “red card” for national parliaments. The success of the enhanced mechanism, however, will depend on how EU institutions and national parliaments make use of it.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article also appears in German on the blog of the Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin, and an earlier version appeared on Der (europäische) Föderalist. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1WKpSjd

_________________________________

Valentin Kreilinger – Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin

Valentin Kreilinger – Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin

Valentin Kreilinger is a Research Fellow at the Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin and a PhD candidate at the Hertie School of Governance. His main research interests are differentiated integration, European and national parliaments and reforming the Economic and Monetary Union. He graduated from the LSE with a MSc Politics and Government in the European Union. He tweets @tineurope

Why will a red card system impact on services for the single market? It’s not going to happen anyway so a red card system will have no more of an impact than that status quo of the past 42 years. The Germans say no so that means no.

A yellow card (or a new red card based on the current model) can only be used on proposals (not final drafts or laws) if the EU has breached subsidiarity, and agree they have. Do you think a Red Card should be useable on existing laws, final drafts and on all laws/proposals not just ones with a subsidiarity issue?