Spain will hold a general election on 20 December, with opinion polls indicating a tight contest between four parties for the largest share of the vote – the governing People’s Party (PP), who have a small lead in most polls, the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Ciudadanos (C’s), and Podemos. Sebastian Balfour provides a final look at the campaigns and the polling. He writes that with Spain’s traditional two party system giving way to a new political landscape, the result remains impossible to predict.

Spain will hold a general election on 20 December, with opinion polls indicating a tight contest between four parties for the largest share of the vote – the governing People’s Party (PP), who have a small lead in most polls, the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Ciudadanos (C’s), and Podemos. Sebastian Balfour provides a final look at the campaigns and the polling. He writes that with Spain’s traditional two party system giving way to a new political landscape, the result remains impossible to predict.

The general elections in Spain on 20 December are likely to transform the country’s political landscape. Polls suggest the end of the two-party system that has dominated Spanish politics since the consolidation of its democracy. The fragmentation of the vote already became apparent in the European elections and the regional and local elections this year.

The central feature of this new landscape is the sudden emergence of two new parties of the left and centre-right, Podemos and Ciudadanos, in a challenge to the political culture of the established parties of Spanish democracy. The legitimacy of the political system is under question after seven years of economic crisis, austerity and unemployment and the unravelling of the corruption and clientelism at its heart. The words that resound in the electoral rallies of the two new parties are renewal and regeneration.

If the polls are to be believed, however, the elections are unlikely to produce a clear result. The contest, it seems, is a four-horse race without a clear winner. The parliamentary arithmetic implied by the polls suggests that no party will emerge with an absolute majority of 176 seats and above in a parliament of 350 seats. When that happens, a second vote is held in the Congress 48 hours later in which the party winning a simple majority of seats is invited to form the government.

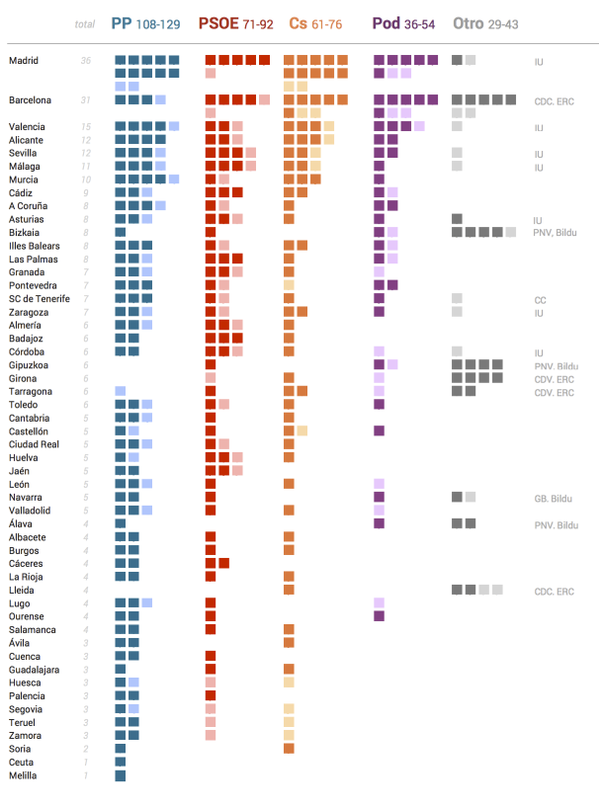

Chart 1: Seat prediction for the Spanish general election

Note: The chart is reproduced with permission from El Español and is provided for illustrative purposes rather than as an attempt by the author to predict the result. The prediction was compiled by Kiko Llaneras based on 15,000 simulations using polling data up to 12 December 2015. Each square indicates one seat in a given location, with darkly coloured squares predicted with 75% certainty and lighter squares with 50% certainty. Party abbreviations are: Partido Popular (PP), Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Ciudadanos (C’s), Podemos (Pod) – ‘Otro’ refers to other parties.

According to opinion polls the ruling Partido Popular (PP) is likely to achieve more seats than any other party. Yet politically it is less likely to form a coalition or minority government. Arithmetically, the PP and Ciudadanos could combine to form such a government. Together, they might muster anything from 169 to around 200 seats.

No combination of the left would be able to reach the same number of seats nor would a coalition of Ciudadanos and the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) without the support of Podemos, an unlikely marriage of convenience, at least on paper, since both Ciudadanos and the PSOE have bitterly opposed Podemos. Much depends on the horse-trading in posts and policies that is no doubt taking place now behind the scenes and will surely intensify in those 48 hours between one Congress vote and another.

The arithmetic pointing to a possible PP-Ciudadanos coalition hardly squares with the electoral commitments made by the parties. This is of course a familiar scenario in many European countries, but the dilemmas it involves are particularly acute in the Spanish case. Ciudadanos emerged at a national level only a year ago partly in reaction to the corruption scandals that were shaking the Popular Party. Its leader, Albert Rivera, has drawn on the British experience of the Liberal Democrats’ coalition with the Conservatives to warn of the danger of the party losing legitimacy in any coalition with the PP.

That is, Cuidadanos is conscious of the risk of contamination with a party tainted by corruption and clientelism. Its programme has attracted voters because it calls for a fundamental renewal of political life, which would involve, among other things, the abolition of the Senate, the transformation of the electoral system, and significant changes to the Constitution, none of which the PP is likely to support.

Given its corruption scandals and uncharismatic leader, the PP’s lead in the polls is somewhat surprising. But it has sought to present itself as the party best able to defend the economy. Following a decline in GDP of 8 per cent between 2008 and 2013, the economy has been expanding for eight consecutive quarters and GDP is now growing at the rate of 3.1 per cent.

The PP also claims to be the best able to defend national unity when faced with the challenge of Catalan secession. Perhaps its greatest test is the rise of Ciudadanos as an alternative party of the centre-right unidentified so far with corruption. This might drive a wedge between centre and right, and the PP, which has always sought to cover the widest possible political spectrum, might find itself identified solely with the right. So the PP’s electoral machine has also turned its guns on Ciudadanos.

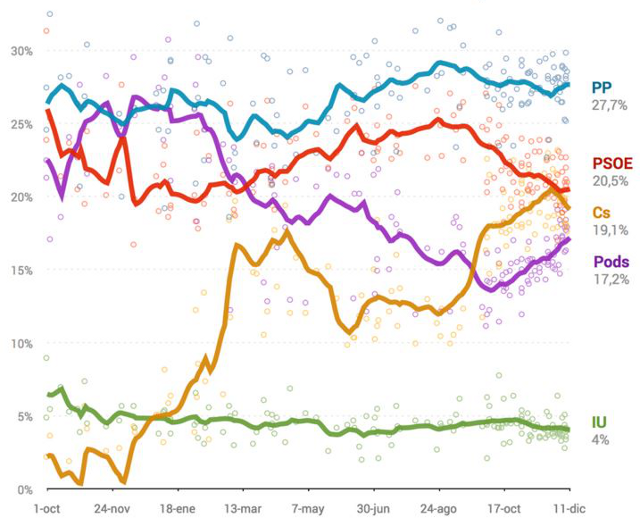

For their part, the Socialists have suffered from a drift of voting intentions towards Ciudadanos on the right and Podemos on the left. Their identification with the old bipolar political system, their handling in power of the economic recession between 2007-11, added to the cases of corruption among local politicians in the Socialist stronghold in Andalusia, have eroded their vote from almost 29 per cent in 2011 to 21 per cent in December 2015, according to a number of polls.

Chart 2: Opinion polling in the Spanish general election (Oct – Dec 2015)

Note: The chart is reproduced with permission from El Español and is provided for illustrative purposes rather than as an attempt by the author to predict the result. The lines represent averages based on the indicated polls (shown in the chart as circles). Party abbreviations are: Partido Popular (PP), Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Ciudadanos (C’s), Podemos (Pods), United Left (IU).

Podemos’ votes have also fallen in the opinion polls from almost 30 per cent in January to 19 per cent in December. It is likely that this fall is connected to the rise of Ciudadanos, which emerged just before the high point scored by Podemos in the opinion polls. Podemos and its regional allies may also have suffered from the polarisation of the two competing nationalisms of Spain and Catalonia, in which questions of identity have trumped economics and social policies.

Its reasoned defence of the right of referendum over independence is cutting no ice in the polarised discourse in both Spain and Catalonia. Podemos is also likely to have lost support on the radical left as it seeks to consolidate its position as a parliamentary party. Its efforts to take on the mantle of the popular rank and file movement 15M may have contributed to the demobilisation of the movement. Also in the competition for the vote for regeneration, the polls indicate that the youth vote tends to support Ciudadanos rather than Podemos, suggesting the continued strength of concern about corruption rather than capitalism.

The polls suggest a complex segmentation of the vote around age, occupation, region, and urban-rural polarities. The PP appears to have lost more than a half of the youth vote it enjoyed two years ago, while more than 20 per cent of the over-65s say they would always vote PP. This age gap is reflected in the age of the candidates. While the President and leader of the PP, Mariano Rajoy, is 60, the leaders of the other three main parties are between 36 and 43 years old. The average age of the PP’s main candidates is over 51 years of age whereas that of the other three parties is much lower. Of young voters, students and the unemployed tend to favour Podemos, while those in work are more likely to vote for Ciudadanos.

Again according to the latest polls, rural areas tend to replicate the traditional two-party vote while cities reflect the new fragmentation of the party system; this favours the two traditional parties because the electoral system privileges the rural over the urban seat. Therefore in terms of votes rather than seats, the shift in voting patterns may well be greater than the results suggest.

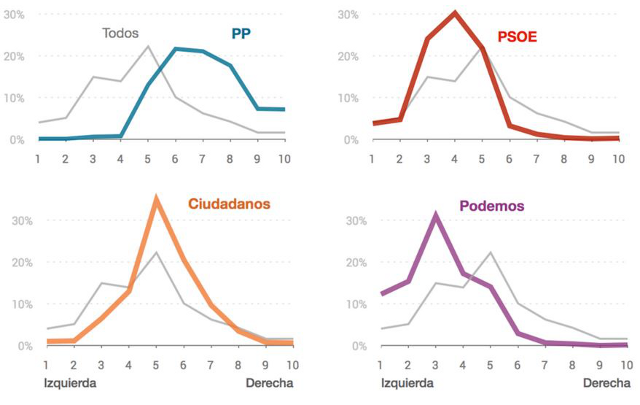

Chart 3: Self-identification of voters for the four major parties on a left-right scale

Note: The chart is reproduced with permission from El Español. The chart shows where voters and ‘sympathisers’ for each party place themselves on a ten point ideological scale between left (izquierda) and right (derecha). For more information on the parties see: Partido Popular (PP), Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Ciudadanos (C’s), Podemos.

Electoral behaviour also varies according to region. The strength of the Socialists remains in the south while the PP continues to enjoy the support of the centre and the north-west. The results in Catalonia will be somewhat overshadowed by the continued problem of negotiating a new government to begin the process of ‘disconnection’ from Spain following the regional elections of 27 September, although the polls suggest a fall in support for the parties seeking independence. In the Basque Country the conservative nationalist party, Partido Nacionalista Vasco, shows continued strength, whereas the radical nationalist party EH Bildu is likely to lose two seats to Podemos while, against the trend elsewhere, Ciudadanos is unlikely to gain any.

Ultimately, the electoral outcome is hazardous to predict for several reasons. The two parties challenging the status quo have only been tested in European and regional and local elections. There are significant variations across all the opinion polls, which in any case do not take into account the current volatility of voting intentions. Also the undecided voters are legion, no less than 41.6 per cent in one poll, making any predictions of the electoral outcome even more risky.

Yet from the polls we might extrapolate two hypothetical scenarios. So far, the Socialists are emerging as the party likely to win the second highest number of seats after the PP, followed at some distance by Ciudadanos and Podemos in a neck-and-neck race for third place. A coalition between the Socialists and Ciudadanos, with the Socialist leader Pedro Sánchez as PM, and with the negotiated abstention of Podemos, could win an absolute majority of seats. Rivera would need to swallow his assertion that he would refuse to take part in a coalition government led by Rajoy, Sánchez or Iglesias. It would suit Podemos to be seen as kingmakers yet also remain in the opposition to continue campaigning for radical change.

A second more hypothetical scenario would flow from the popularity stakes of the four party leaders which Rivera leads by some margin. A late surge in support for Ciudadanos among undecided voters might conceivably lead to a Ciudadanos-Socialist coalition led by Rivera. All bets are off. The uncertainty of the electoral outcome is a measure of the transformation of the Spanish party system.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1O7vudg

_________________________________

Sebastian Balfour – LSE

Sebastian Balfour – LSE

Sebastian Balfour is Emeritus Professor of Contemporary Spanish Studies in the LSE’s Department of Government.

Very nice overview of a complicated election.

The interesting thing about chart 3 is the PP. They have voters even among those who say they are “10” on a right wing scale. In other countries these votes go to a party on the far right – a UKIP, Front National, PVV, etc. Here the PP are getting 15-20% of their support from 9 and 10 on the ideological scale but also appealing to the centre and that seems to me exactly why they’ll win.

Good piece, I agree the PP is a curious phenomenon, a kind of catch-all party of the Right.

Equally striking is how far to the Left the self-identification of Spanish voters remains in general. This has been the case for many decades, or at least for many periods since 1977.

And there is also the very suggestive overlap between the self-positioning of Podemos and PSOE voters. In fact they have broadly the same electorate, peaking at 4 for the PSOE and 3.5 for Podemos on theLeft-Right ideological scale.

The only difference seems to be that there are larger quantities of left-wing voters for the PSOE, whereas Podemos has a few more left-wing ones. Clearly they should have been one party and looking to the future, they had better stop the squabbling, revise their strategies, and unite.

You are joking. Podemos is not a democratic party. Its economic and political links to Veenezuela prove it. Its leader Pablo Iglesias personally runs a TV channel financed by Iran, no less.

Podemos is the symptom of a disease cálled bad governance which affects all the Spanish “ruling classes”, its leaders and many of its members; politicians, judiciary, police, the civil service and business leaders.

The amazing levels of corruption and the misery affecting so many Spaniards has generated Podemos. Podemos integrates traditionally antisystem people plus many ordinary people so angry they no longer care about the whole system. It is, once more, the reaction to bad rulers whose actions brought the French Revolution, Lenin, Fidel Castro, Mao, Chavez, the Spanish Civil War and on and on.

The Spanish Socialist Party is not like Podemos. It is a party that does not want to destroy the system. Podemos does. Unfortunately, like the Popular Party, it is thoroughly corrupt.

Podemos now p,oses as democratic. It is just a ploy to gain power, just like Chvez did in Venezuela.

You either do not know Podemos or you areea Podemos supporter trying to portray the Party as “democratic left”.

Sadlly, in Spain we have the formal aspects of democracy. Reasonably real demogracy and a social-capitalist system close to Northern Europe’seis as far from Spain as Denmark’s climate is from Spanish climate.

The saddest part is that the Spanish educational syistems, at all lavels, keeps pumping out citizens unprepared andeunfit to build democracy and social-capitalism.

No, I’m not joking, and no, I’m not a Podemos emissary. As with all Spanish parties, to become legalised a party must have a formal democratic elective structure, which is more than you can say for the British Conservatives.Obviously party leaders can try and distort these structures and much admired politicians like Felipe Gonzalez – and Pablo Iglesias in a different way – tend to get their way bypassing procedures. But having links with Venezuela where – like it or not – Chávez won many formal elections, does not allow anyone to label them undemocratic.

As to “amazing levels of corruption”, yes, it’s amazing that there should be corruption in Spain given the ways things were in the 1970s but Transparency International’s Index – created out of about 7 surveys trying to gauge corruption – sees Spain as the 38th least corrupt country out of 174 in the world – on a level with Israel. That’s way below many European countries, yes, but above a host of Eastern European countries and certainly not even comparable with Italy, ranked 69th. The UK is 14 down from the top, perceived as a bit more corrupt than Singapore and Australia.

Most importantly, if you research the official results in depth on the El Pais website, Podemos has won consistently at least 15% or often 20% of the vote in vast swathes of villages and small town local council areas throughout the country, many times coming 3rd, 2nd above the PSOE even in traditionally Socialist-leaning Andalucía and in the areas where the PP was the most voted. But of course, mostly they didn’t win the seat. In this sense, Podemos has inherited the PSOE’s old grassroots vote, not a new cross-section of Spanish society. Their presence all over the country and not just in large towns shows Podemos is not the urban phenomenon of the traditional New Left. People living in remote areas have felt very let down by the PSOE, evidently. In the shadow of the economic crisis, Spain is a strongly left-wing country, but a disunited one.

An excellent analysis and discussion. I also agree that the PP is a rather curious phenomenon in terms of who votes for it. I studied at the University of Salamanca, in 2003 and it was surprising to me just how many young people were PP voters, in spite of the fact that students were then, just as they are now, typically more associated with voting for left wing parties. Regional variations are, therefore, likely to play as significant a part in this election as demographics.

My view is that the prospects for change are still very much open to question. Some sort of ‘anyone but Rajoy’ coalition is possible. I am sure that the PP will gain the most seats, however, assuming the PSOE does manage to maintains second place, the question is whether Rivera will be able to resist the allure of government through establishing a coalition with Sánchez.

Another possibility that may merit further discussion is the possibility of pacts in key areas of legislation. Such a policy allowed Aznar to successfully manage minority PP government from 1996-2000. However, in view of the current divisions between the four parties, this is much less likely to happen than during the two party politics that characterized that period.

Finally, it is conceivable that there will be little change at all. There are still a significant proportion of voters who remain undecided, and, drawing parallels with the influence of the perceived threat from the SNP on voters in England back in May, there may be a last minute swell of support for the PP around the idea of the Spanish nation.

I found SB’s article and the 5 comments very useful and well-informed. Having been severely alienated over the years by the two main traditional parties in Spain, PP & PSOE,I was expecting the electoral implosion of both and a radical re-ordering of the political map, an ‘ajuste de cuentas a fondo’ by the 25 million citizens who voted. This has not happened so far, despite grievous losses of seats in both cases. What I still cannot fathom was the PP’s model of governance since 2011-12, i.e. ‘do nothing’ and don’t go after other guilty parties, especially the PSOE re: the ‘autoria del 11M’ and the PSOE bosses in the bankrupt Junta de Andalucia, plus the treachery of the Generalitat under Mas and Junqueras, exploiting the independence card to cover up huge corruption and illegal offshore fortunes belonging to Catalan politicians and oligarchs. Rajoy’s tenure as PM has been shameful, dysfunctional and destabilising. Moreover, rather than shrug off the terrifying ‘punetazo’ to the head in Pontevedra (16/12/2015), he should have called for a full police enquiry of such a despicable, unprovoked attack by a 17 year old ‘maton’. Observance of the law is both a right and a responsibility and no one should be immune from scrutiny. Sadly, Rajoy’s habit of turning a blind eye, linked to his quietism and cowardice, has subverted not only effective PP governance but also allowed the enemies of democracy to flourish in Spain. And here I have to differ a little with my old colleague Monica Threlfall, at least with regards to the aims and strategies of Podemos and Pablo Iglesias. The so-called ‘monaguillos de la Complutense’ who trained in Venezuela as political advisers, may claim democratic credentials on official electoral papers, but their real agenda, in my view, is different. It is modelled upon the electoral ‘golpismo’ of Hugo Chavez and the brutaIity of the Castro gang (which has around 100000 Cuban soldiers occupying Venezuela at present, protecting ‘Cuban’ oil and Maduro’s cities from riots). As Victor’s notes suggest, Podemos is inspired by the very same totalitarian ideology which underpinned Castroist collectivism and Chavista ‘bolivarianismo’ in the failed military coup of 1992, for which “El Comandante’ was jailed. Chavez may have won the general elections of 1998 in Venezuela ”formally’, as Monica indicates, but his methods were not inspired by democratic motives, rather by Chavez’s personal political fantasy as a saviour and liberator, backed by his creation of huge popular client groups and a vast dependency culture, based on bribes and free services, paid for by dwindling oil revenues. Incredible as it may seem, in November 2015, Pablo Iglesias managed to ‘fichar’ or sign up General Jose Julio Rodriguez as prospective party candidate for Zaragoza and personal mentor in security and military affairs; this man was also the highest ranked and overall commander of Spain’s armed forces between 2008-11, before moving to the ‘reserve’; the ‘fichaje’ was a thunderbolt from the blue, which shocked the PP government; the general was promptly sacked from all official reserve military duties and benefits. But most astonishing and unprecedented of all was Iglesias’ boldness and cynicism in signing up Rodriguez as a potential Minister of Defence, in the event of a Podemos electoral victory. In my view, the ground was being prepared and tested, not for democratic negotiation and consensus among the parties, but for a potential militarisation of government policy at some stage, in the face of mass public rejection of unpopular Podemos measures. Here, General Rodriguez would appear as trustworthy Defence minister, charged with reassuring the police and army to do their disagreeable ‘democratic’ duty while crushing any public disorder. Meanwhile, Iglesias was recruiting potential party members and Podemos candidates from within Spain’s para-military Civil Guard, despite their duty to observe political neutrality. But who cares? This is the same kind of flexible neutrality which places Podemos, ETA and Bildu on the same ideological ground, all happily engaged in enforcing their control and domination of the Basque mafia state.

Fascinating story, Barry, I didn’t know about it. I was guided in my thinking by the absolute overlap of their electoral bases. The General Rodríguez affair probably accounts for so many PSOE leaders especially regional leaders refusing to work with Podemos – though on the surface it’s the Catalan independence question which is key to their refusal.

Now we hear that Iglesias is seeking a dialogue over keeping the PP out of power. The terms are moderate: “Los consensos de base para el diálogo son, además de la lucha contra la corrupción y la desigualdad, una batería de medidas de emergencia social, la derogación de “las peores leyes del PP” –—de la reforma laboral a la ley mordaza— , y la reforma del sistema electoral.” (El Pais 3.01.16) They may also park the question of the Catalan referendum for a while. The PSOE yet again is embroiled in an internal dispute about when to hold their party Congress, instead of forging an alliance to govern the country.