Economic convergence is generally taken as an important requirement for the euro area to function correctly. Without this, the significant differences between euro area economies could make sharing a currency problematic. As Anna auf dem Brinke writes, however, political and market forces have so far proven unable to prevent imbalances between member states. She argues that new convergence goals should be a key priority for the euro area and suggests a number of principles for choosing better convergence indicators.

Economic convergence is generally taken as an important requirement for the euro area to function correctly. Without this, the significant differences between euro area economies could make sharing a currency problematic. As Anna auf dem Brinke writes, however, political and market forces have so far proven unable to prevent imbalances between member states. She argues that new convergence goals should be a key priority for the euro area and suggests a number of principles for choosing better convergence indicators.

It was clear from the beginning that the euro area was no optimal currency area and lacked mechanisms to correct imbalances. Yet, there were two hopes (and also one big worry). The first was that market forces would bring about more convergence. By introducing a single currency, markets would integrate even further, making asymmetric shocks less likely. The second hope was that economic integration would ultimately also lead to political integration. The institutional set-up was far from complete, but building it on the way was seen as the essence of the European project.

At the same time, countries worried about moral hazard. Member states of the euro area would free-ride on a low ECB interest rate guaranteed by the other countries while over-spending at home. Therefore, the EMU introduced deficit and debt rules that member states in the euro area had to follow. Yet adjustment proved difficult and the rules in the Stability and Growth Pact were routinely missed. In 2011, they were complemented by a host of new measures in the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure, which monitors a range of macroeconomic indicators. Since then, some imbalances have been slightly corrected. But overall, market forces and policy measures were insufficient to bring about enough convergence.

From convergence to divergence and why it matters

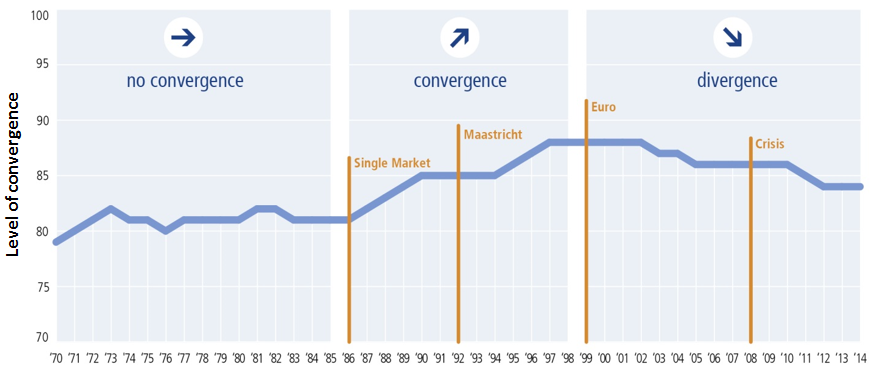

The divergence in the euro area is evident in many different macroeconomic indicators. One interesting cut is to take the euro area countries and track how the group became more (or less similar) before and after the introduction of the euro. The figure below shows differences in real GDP per capita (in PPP) within the group of euro area 11 countries. These are the countries that adopted the euro in 1999. (For each year, the euro area 11 average is set to 100 and then the standard deviation is subtracted.)

Figure: From convergence to divergence in the euro area

Note: The Chart is produced by the Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin and the BertelsmannStiftung. The figure shows real convergence in the euro area 11 since 1970. The countries which adopted the euro in 1999 are Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Spain, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal and Finland (excluding Luxembourg, which is an outlier). Real convergence is shown as the inverse standard deviation of GDP per capita in PPP (purchasing power parity) from the euro area 11 average. A value of 100 signifies full convergence. Source: OECD, authors’ calculations.

With the start of the single market project in 1986, countries started to converge rapidly. Around the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, a new convergence wave was unleashed. Since 1998, however, and just one year before the introduction of the euro, countries have started to diverge. This trend has continued, and was halted only temporarily by the crisis in 2000: the year in which all countries slipped into recession. All in all, the euro area countries first converged rapidly and then diverged significantly.

The reversal of the trend poses a threat to the euro area for three reasons. First, the euro area has a low-growth and high-unemployment problem. This erodes social cohesion and public support for the single currency. Second, the European Central Bank only sets one interest rate on the basis of the weighted average rate of inflation in the euro area. As countries diverge significantly in their economic performance, this single interest rate is not only suboptimal for most countries, but also contributing to misallocation within the euro area. Third, the euro area lacks instruments to address growing imbalances. Once they occur, they are very difficult to correct and adjustments tend to be painful, as the recent debt crisis has shown. Before we can tackle the first challenge, we have to address two and three.

Choosing indicators for a new convergence process

In June 2015, the Five Presidents announced that they would launch a new convergence process based on better indicators. Fostering convergence is a difficult task. Indicators can play a key role. They should be chosen with two objectives in mind: First, we should have clear, simple, and easy to remember headline indicators to steer the process. Second, the rules and indicators should alert to growing imbalances that are difficult and costly to be tackled down the road and destabilise the euro area.

There seem to be three good candidates for the new convergence process. First, one indicator should monitor inflation differentials. If inflation rates diverge significantly, the ECB´s interest rate is a one-size-fits-none rate. It leads to booms in countries with higher inflation than the euro area average, and to low growth in countries with lower than average inflation than the euro area average. Inflation differentials between euro area countries should be as small as possible.

A second indicator should monitor competitiveness in the euro area because external devaluations are no longer an option and internal devaluations are costly. As countries have given up their monetary policy, they can only reduce prices by cutting wages, which is economically and politically difficult. Productivity rates and unit labour costs in each country should grow in line.

Last, we need to address the problem of account imbalances. Both persistent deficits and persistent surpluses pose a problem for the euro area. Research has shown that excessive deficits and surpluses lead to crises. High and persistent deficits may lead to default. High and persistent surpluses weaken demand. Over the course of the business cycle the current account should be kept in balance.

No single indicator will be perfect. But the euro area can still do better. The crisis has taught us that growing imbalances undermine the stability of the euro area and lead to disaster. Rethinking convergence in the euro area will make the euro area viable and improve the conditions for growth and employment in the future.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Mikka Luster (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1UxhttT

_________________________________

Anna auf dem Brinke – Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin

Anna auf dem Brinke – Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin

Anna auf dem Brinke is a Research Fellow at the Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin. She is a political economist working on economic policy in Europe. Prior to joining, she completed her PhD at the European University Institute. Anna holds an MSc from the London School of Economics and a BA from University College London.