Ireland was one of the countries hardest hit by the financial crisis, however it has emerged with a strong recovery and now boasts the fastest pace of economic growth of any country in the Euro area. But what explains the Irish recovery and could it act as a model for other Eurozone states? Aidan Regan writes that contrary to the interpretation put forward by some policymakers, the recovery has had little to do with structural reforms or austerity policies, but instead reflects a successful development strategy focused on securing foreign direct investment, particularly from the United States.

Ireland was one of the countries hardest hit by the financial crisis, however it has emerged with a strong recovery and now boasts the fastest pace of economic growth of any country in the Euro area. But what explains the Irish recovery and could it act as a model for other Eurozone states? Aidan Regan writes that contrary to the interpretation put forward by some policymakers, the recovery has had little to do with structural reforms or austerity policies, but instead reflects a successful development strategy focused on securing foreign direct investment, particularly from the United States.

It has been a truly remarkable few years for Ireland and the European Union. In the space of five years Ireland has gone from being the basket case of the European Monetary Union to its number one success story. Economic growth is now the strongest in the Euro area, and according to the most recent data, this growth is having a real impact on employment. The dominant narrative among policymakers in the EU is that other peripheral states of the Eurozone should follow the Irish adjustment back to the market.

This leads to two important questions. First, what explains this remarkable turnaround in fortunes for Ireland? Second, why are other Eurozone countries that pursued a similar adjustment still struggling to recover? In reality, the Irish recovery has nothing to do with austerity induced cost competitiveness and everything to do with a State-led enterprise policy to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) from the United States.

What really explains Ireland’s recovery?

Let’s unpack the official story. The European Commission argues that the Irish recovery is an outcome of the government’s successful implementation of their structural adjustment programme. This technical adjustment can be explained as follows. Ireland had to increase taxes and implement radical cuts in expenditure to bring down its fiscal deficit. Given that Ireland had lost competitiveness during the 2000s (measured as increased labour costs), wages also had to be reduced.

A reduction in wages and public expenditure negatively impacts domestic demand. But this negative effect is offset by the positive effect on exports. A strong state commitment to macroeconomic stability and improved cost competitiveness improved the real exchange rate (REER) and facilitated an export-led recovery. Put simply, a growth in external demand (consumers outside Ireland buying more Irish produced goods and services) compensated for a contraction in the internal demand caused by austerity (Irish consumers, households and government spending less). It’s the German model of adjustment: commit to macroeconomic stability, compress domestic demand and expand exports.

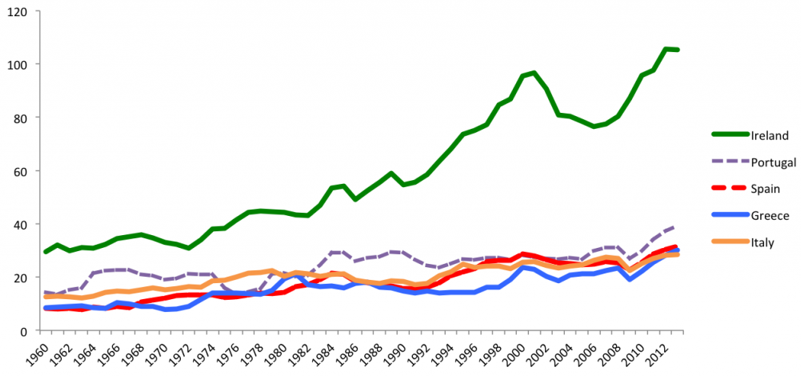

Figure 1: Exports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP in selected countries

Source: World Bank

Figure 1 clearly shows that from 2008 Ireland has experienced an export-led recovery vis-a-vis other crisis afflicted countries of the Euro area. But is this growth in exports really associated with an improvement in price competitiveness? For the European Commission, a decline in competitiveness runs as follows: increased labour costs results in more expensive products, this causes a decline in exports, which culminates in a current account deficit. Therefore an improvement in competitiveness should equate with declining labour costs leading to better-priced products, an associated increase in exports, and ultimately an increased current account surplus.

This model of competitiveness assumes a traditional industry and a classic manufacturing firm (think shoemaking, candle-making or metal fabrication). The shoemaker who reduces (or at least stabilises over a long period of time) the labour costs of his/her workers will be able to sell more shoes at a better price in bigger markets. It is this logic that underpins the structural reform strategy of the European Commission. National governments that reduce rigidities in their product and labour markets increase competitiveness, which in turn facilitates an export-led growth in a period of austerity.

The problem with this old fashioned concept of competitiveness is that the firms driving Ireland’s export-led recovery are in high-wage price inelastic sectors (biotech, pharmaceuticals, finance, business and computer services). What this means is that their products are less sensitive to movements in international prices. According to recent data from the CSO job churn survey, these sectors of the Irish economy (particularly high-tech ICT and Finance) experienced increased not decreased labour costs during the period of adjustment. They have been increasing wages and expanding jobs before, during and after the crisis.

It is worth restating this clearly as it has important policy implications: Ireland’s thriving export sectors increased wages and jobs in a period when the public sector was reducing wages and costs. These exporters are primarily large US multinational firms who trade in complex international supply-chains in the expanding service sectors of the global economy.

The German-EU structural reform agenda is premised on the assumption that all countries are built around the Rhine-Westphalian metal manufacturing firm, where the classical model of competitiveness does apply. Ireland’s manufacturing sectors have been in decline for over a decade (computer hardware, optical equipment and medical machinery). It is true that if these firms (and the government) had radically cut wage costs in the 2000s (in order to compete with Eastern and Central Europe) then these firms could have been kept in Ireland. But would we call this competitive success?

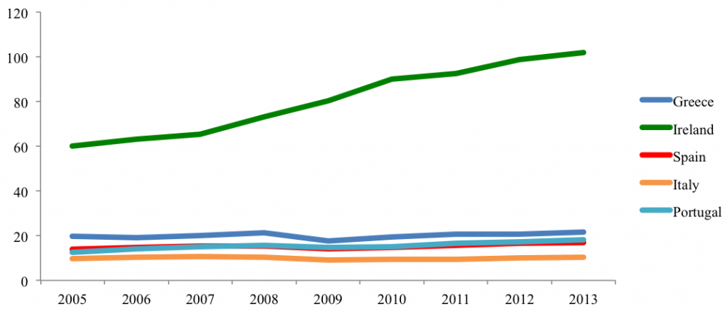

Figure 2: Trade in services as a percentage of GDP in selected countries

Source: World Bank

The most important observation on Ireland’s export-driven recovery since 2009 is that it has occurred in the internationally traded services sectors of the economy (see Figure 2). In particular, it is associated with an expansion of those firms selling ‘computer-tech services’.. This expansion in ICT services has generally compensated for the decline in ICT manufacturing. From 2014 domestic demand also increased in Ireland (central to employment) but this was preceded by a renaissance of the export engine.

Many commentators argue that the expansion of traded services is a total illusion and that there is no recovery at all. Those critical of the austerity agenda argue that the supposed growth in service exports reflects an accounting entry by US multinationals rather than real economic activity. It is a tax evasion strategy by Google and Apple that makes Ireland’s adjustment look like a success story, whereas in actual fact the adjustment has decimated local Irish producers, who predominantly trade with the UK. Ireland is simply creaming off rents from the US tax avoiding US MNC sector.

There is an element of truth in this, much like there is an element of truth in the macroeconomic stability and cost competitiveness structural reform narrative. ICT computer services now account for over 50 per cent of Irish service exports. This is primarily driven by large global US multinationals such as Google, Oracle, Facebook, Adobe, Linkedin, Amazon and Microsoft, to name but a few (research by the author suggests that over 100 US tech firms have located in Ireland since 2004). Total service exports now account for approximately 90 billion, and a handful of global tech-Internet firms, born out of Silicon Valley, now account for around 40 billion of this.

The revenues of Google and Apple are astronomical, and despite most of this being generated through complex global supply chains, a large part of it is booked in Ireland for tax purposes. Therefore, the figures are undoubtedly exaggerated. However, recent data from the annual Forfás employment survey does suggest that there has been a rapid expansion in jobs in the computer services sector, compensating for a decline in manufacturing jobs. To put this expansion in a qualitative context, Google established its Dublin European base in Dublin in 2004, employing less than 50 employees. They expanded during the crisis and now employ over 2,500 workers. Overall ICT services jobs increased from 2,900 in 2008 to almost 12,000 in 2013. In total, over 104,000 full time jobs have been created since 2012.

The export-driven Irish recovery is real (albeit somewhat exaggerated) and it is primarily occurring in the high-tech (and high-wage) sectors of the economy, leading some to conclude that Ireland is experiencing the side-effects of a new emergent Tech bubble in Silicon Valley. Provisional research by myself and Samuel Brazys does suggest that Ireland is indirectly benefiting from quantitative easing in the United States. But the important point to note is that this expansion of inward investment has nothing to do with the policies of the Euro area or the Irish fiscal adjustment. It is the direct effect of a path dependent state-led developmental strategy to attract inward FDi from large global firms in high-wage, high-tech service sectors.

To explain the Irish economic recovery one must trace the role of the state in the development of high-technology industries. Irish enterprise and industrial policy is built around low corporate taxes and liberal labour markets. But this alone does not explain the expansion of Internet tech sector. The latter is related to the cluster effect of having a large pool of workers with general experience of working in the tech sector, and experience of the corporate culture of working in large US multinational corporations. Once Google set up in Ireland in 2004, and Facebook in 2008, they were soon followed by at least 80 other tech companies, and most of these companies source their multi-lingual labour force from across the European Union.

The public policy story of Ireland’s FDI-development strategy has very different policy implications than what is being prescribed to Greece to get out of the crisis. To begin with, the industrial-enterprise policy begins in the public sector not the market. The core actor driving the Irish development strategy is an international network of low-key but highly influential political actors working for the State. Central to this is the role of the Industrial Development Agency (IDA), a public sector agent tasked with attracting inward investment. The IDA are successful at “attracting US winners” not because of a specific administrative state structure but because they have the policy autonomy to operate independently from political parties in government.

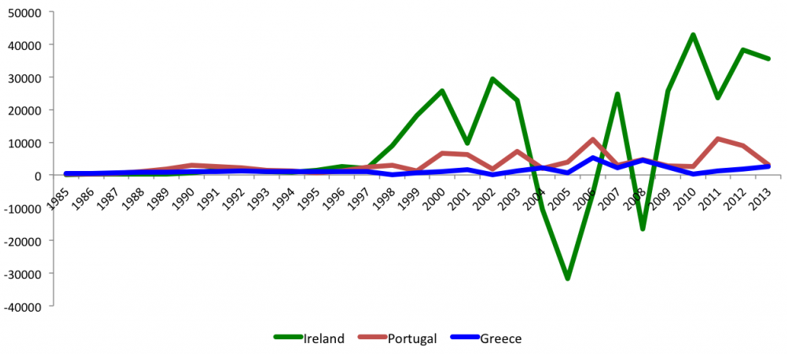

Figure 3: Foreign Direct Investment inflows to Ireland, Portugal and Greece (millions of US dollars)

Source: World Bank

We need new words to describe what the state does and therefore it is important to call the Irish recovery what it is: a state-led development strategy, coordinated by an autonomous public sector agent, specifically tasked (and adequately resourced) to attract investment from global firms in an internationally liberalised market (see Figure 3). Most economists assume that this type of state strategy will lead to clientalistic rent-seeking. All the state has to do is set rules, regulate for market competition and then get out of the way of private business.

Therefore it is assumed that market liberalisation, not politics, shapes export success. This is the assumption that underpins the analyses of industrial and enterprise policy conducted by the European Commission’s Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs. The only role for the state is to implement structural reforms of product and labour markets. Once this liberalisation is achieved the positive effects of inward investment and entrepreneurship will emerge, naturally, by itself.

In the Troika memorandum of understanding with the Irish government, and the country specific recommendations on how to tackle macroeconomic imbalances, there is no mention of enterprise, education, skills or industrial developmental policy. Micro-economic supply-side policies imply nothing more than reducing costs, particularly in the labour market.

None of this is meant to suggest that if Greece and Portugal develop a functional equivalent to the ‘Irish Enterprise State’ they will somehow develop the conditions for export growth. The Irish FDI-State did not suddenly emerge in 2009, but can be traced right back to the 1960s. As Seán Ó Riain has illustrated, it is a deeply embedded development project that has evolved over time. The most recent major change occurred when the IDA and its affiliate agencies gave increasing priority to attracting ‘born on the internet’ firms, and to shift from attracting ‘hardware’ to ‘software’ digital enterprises.

The enterprise strategy is not to capture a whole industry but to attract parts of a firm’s supply chain that specialise in specific activities of an industry. In the high-tech Internet firms that now operate in Ireland, most of the focus was put on establishing marketing and sales. The state and the IDA, in effect, nurtured these large multinational firms over many years and offered executive leaders a ready-made business model for their companies to establish operations in Ireland, which in turn immediately enabled them to overcome various collective action problems in the local market: sourcing office space, recruitment agents, and linking into domestic supply-chains.

This is not a normative celebration of Ireland’s development model. One of the biggest trade offs in prioritising FDI, and foreign-owned companies, is a lack of priority accorded to the indigenous enterprise sectors, not to mention the social justice issues surrounding a general neoliberal friendly market. But when you compare the trajectory of sectoral change in Ireland to Finland it is perhaps unsurprising that the Irish State puts more emphasis on attracting large global firms as a replacement for declining manufacturing industries.

Both Finland and Ireland have experienced a rapid decline in the computer manufacturing sectors since 2005. In Finland there has been no replacement in the ICT services sector, creating a serious crisis of their export and employment growth model. This is not the case in Ireland, given that the state has actively nurtured ‘born on the internet’ firms emerging out of Silicon Valley. There was a recognition that competitive success (and attracting inward FDI) is unlikely to occur in those high-tech manufacturing sectors that can produce their goods at a fraction of Irish labour costs, and therefore the strategy is to attract global multinational corporations in internationally traded services, who do not compete on labour costs.

Whether one likes it or not, the core policy shaping economic recovery in Ireland is the outcome an embedded relationship between the public sector and large foreign owned global tech firms. This deeply embedded role for the state in the international market underpins Ireland’s capacity to make the transition to export-led growth in internationally traded services, rather than austerity, declining labour costs or macroeconomic stabilisation.

It is, fundamentally, about strategic political decision-making, and economic coordination rather than market competition. If the European Commission is serious about generating the conditions for economic and employment growth in the Euro area it needs to rethink its textbook approach to supply-side “structural reform”. It needs a State-led industrial and enterprise policy.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1QTPwOq

_________________________________

Aidan Regan – University College Dublin

Aidan Regan – University College Dublin

Aidan Regan is Lecturer in European political economy at the School of Politics and International Relations (SPIRe) in University College Dublin (UCD), and Director of the Dublin European Institute (DEI). Follow him on Twitter @aidan_regan for more analysis.