Following the first round of Austria’s presidential election, Norbert Hofer of the Freedom Party (FPÖ) and the Green-affiliated independent candidate Alexander van der Bellen will contest the second round of voting on 22 May. However for the first time in the country’s post-war history, the next President will not be backed by either of Austria’s two traditionally dominant parties, the SPÖ and ÖVP. Philip Rathgeb and Fabio Wolkenstein write that the election marked a watershed moment for the country’s party system, suggesting that only a radical change of strategy can prevent the two mainstream parties from losing power at the next parliamentary elections.

Following the first round of Austria’s presidential election, Norbert Hofer of the Freedom Party (FPÖ) and the Green-affiliated independent candidate Alexander van der Bellen will contest the second round of voting on 22 May. However for the first time in the country’s post-war history, the next President will not be backed by either of Austria’s two traditionally dominant parties, the SPÖ and ÖVP. Philip Rathgeb and Fabio Wolkenstein write that the election marked a watershed moment for the country’s party system, suggesting that only a radical change of strategy can prevent the two mainstream parties from losing power at the next parliamentary elections.

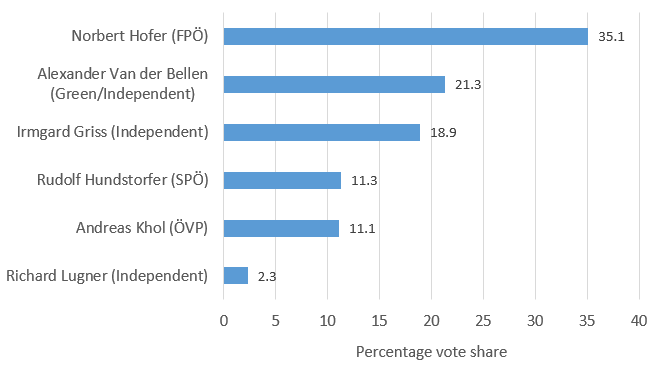

In the words of Heinz-Christian Strache, the leader of the right-wing populist Freedom Party (FPÖ), it was the ‘beginning of a new political era’. The party’s candidate, Norbert Hofer, came a comfortable first with over 35 per cent of the vote in the first round of the Austrian presidential elections on 24 April. And while the result of the second round of voting on 22 May remains to be seen, Strache is clearly right about the broader picture in Austrian politics.

Traditionally, political scientists have considered the Austrian presidential election to be a ‘second-order election’. And rightly so: in practice, the President is no more than a ceremonial figurehead. The 2016 presidential election, however, is not merely about electing a new Federal President. Above all, the outcome of the first round of voting was the most powerful expression to date of the transformation the Austrian political landscape has undergone in the last three decades. This consists chiefly in the erosion of the duopoly between what were historically the two major parties, the Social Democrats (SPÖ) and the conservative Christian Democrats (ÖVP).

For most of the post-war era, the SPÖ and ÖVP governed in a grand coalition. And each President since 1945 was either a member of one of those parties or an independent candidate who enjoyed the support of one of the parties. A brief glance at the results of previous presidential elections suffices to demonstrate how dominant the SPÖ and ÖVP were. Until 2016, the candidates of the two parties together received far more than two thirds of the vote, sometimes even more than 90 per cent. This time, however, both of the major parties’ candidates fell below the 15 per cent mark, receiving less than one third of the vote altogether. This is a clear signal that public discontent with mainstream parties has reached an all-time peak.

Chart: Result of the first round of the 2016 Austrian presidential election

Note: Figures from Bundesministerium für Inneres

There are a number of reasons explaining this trend: the erosion of traditional societal camps, often called Lagermentalität in Austria; decreasing economic growth and increasing economic inequality; the salience of the immigration issue; and, last but certainly not least, pervasive public disaffection with the ‘party cartel’ of the SPÖ and the ÖVP, together with its entrenched system of party patronage.

But even if the magnitude of the FPÖ candidate’s victory caused a major splash in Austria – the second-strongest candidate, Alexander van der Bellen, garnered only 21 per cent of the vote – from a comparative perspective, the extraordinary stability of the Austrian political system is in many respects more intriguing than its transformation. Simply surveying the parliamentary transformations that have taken place in such diverse countries as the United Kingdom (the rise of Thatcherism), Italy (Tangentopoli), Denmark (the 1973 earthquake elections) or even Germany (repeated left-right shifts) should underline that the relative continuity experienced in Austria is something of an exception.

Even though a steady stream of electoral losses has increasingly undermined their dominant position, the SPÖ and ÖVP have remained in government for the majority of the last three decades. Seen in this light, the erosion of the seemingly eternal grand coalition is by no means counterintuitive or surprising: it is an expression of a more general cross-national trend towards party system fragmentation across Europe.

Who benefits from the erosion of the grand coalition?

As the result of the presidential election indicates, the main beneficiary has been the Freedom Party. The FPÖ’s support is steadily growing: for more than a year it has topped every representative poll, being consistently backed by around 30 per cent of the respondents. The SPÖ and ÖVP are presently trailing by 5-8 points.

If this trend persists, it is far from unlikely that the FPÖ will win the next general election in 2018, and therefore provide the next Chancellor of Austria. This scenario has been a major topic of debate in the presidential campaign, since Alexander Van der Bellen, the former chairman of the Green party who came in second place, announced that he would make use of the President’s formal powers to block a coalition led by the FPÖ. Van der Bellen said that he considers the FPÖ’s position on the European Union – the FPÖ may generally be described as Eurosceptic – incompatible with the constitutionally entrenched commitment to European integration, and ultimately detrimental to Austria’s interests.

Tellingly, the scenario of Van der Bellen blocking a possible FPÖ-led government appears to be the most likely way of frustrating the FPÖ’s ambitions to hold office. It is difficult to imagine that any other political party in the Austrian political system could provide a credible alternative to the populist right and successfully challenge the FPÖ in the political arena.

This signals that the fragmentation of the party system is at least partially a result of substantial political failure on the part of the political mainstream. The SPÖ and ÖVP would do well to recognise that generic campaign slogans fabricated by overpaid PR agencies and mere gesture politics will never convince voters to turn their back on the FPÖ. The only way in which they can regain electoral attractiveness is through a radical break with the status quo. This must involve genuine intellectual and programmatic renewal, with voters being offered a clear and distinctive political vision addressing the electorate’s concerns. Importantly, this means that they must also provide principled and prudent proposals concerning the salient and polarising issues of immigration and integration.

But the SPÖ and ÖVP must also put their efforts and energies into rebuilding their long-lost connection with the citizenry. This cannot be done solely through party patronage, the strategy the SPÖ and ÖVP have traditionally pursued. Providing affiliated people with leadership positions is somewhat different from taking the political demands and concerns of the populace seriously. Rather, it must involve extensive reform of the party structure, moving away from the present hierarchical system which undermines the transmission of preferences from the bottom up.

To be sure, it has become almost commonplace to suggest these things. But, at least in Austria, the need for party reforms has never been more urgent. If the SPÖ and ÖVP fail to learn the lesson of the 2016 presidential elections and remain unwilling or unable to transform their internal structures, they will soon not only be out of touch with the voters but unable to exercise political agency. And what’s more, few would shed a tear at their demise.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: PES Communications (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1X6sBSw

_________________________________

Philip Rathgeb – European University Institute

Philip Rathgeb – European University Institute

Philip Rathgeb is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute in Florence.

–

Fabio Wolkenstein – LSE, European Institute

Fabio Wolkenstein – LSE, European Institute

Fabio Wolkenstein is a PhD candidate at the LSE’s European Institute. He has published work in several journals including the Journal of Political Philosophy and the American Political Science Review.

Of course the two old parties are constrained in terms of what they present to the electorate by their need to adhere to ever greater control by the country’s affairs by the EU. ‘Grand Coalitions’ are a polite and grandiloquent euphemism for saying that you have voted for two parties when in fact they can easily become one – ie that you have no meaningful choice. They have become easier with the ever greater control by the EU, as whoever you vote for (see Greece a year ago to date) and whatever you say in a referendum (see Greece again last year) you have to do as you are told at the end of the day. Easier to affect minor differences during a campaign and then allow democracy to go to sleep again.

With the abandonment by the traditional left of anything other than mild complaints about EU-driven austerity, and its almost total acceptance of the New Order, it is left to candidates like those of the FPÖ to fill the void. It seems that almost all of Europe is sleepwalking towards this. The elite probably thinks it can again suspend democracy if it has to (the EU deposing the Greek and Italian government a few years ago, installing its own man at the top), but this might become trickier and trickier. A stooge of the establishment van der Bellen suspending democracy by gerrymandering the Constitution on their behalf and trying to stop the majority party coming to power if it is elected, as is likely? Then what? As you seem to suggest, the elite has only itself to blame – but not just in Austria, right across Europe.

Congratulations to the FPO, they deserved this, the only one of Austria’s party’s who actually listened to the electorate.