Germany has recently voiced criticism of the European Central Bank (ECB) from the perspective that its policies, such as quantitative easing, have a particularly negative effect within Germany. Benjamin Braun argues that while there have indeed been German losses from the ECB’s policies, much of the problem stems from the country’s reluctance to ease its own fiscal policy.

Germany has recently voiced criticism of the European Central Bank (ECB) from the perspective that its policies, such as quantitative easing, have a particularly negative effect within Germany. Benjamin Braun argues that while there have indeed been German losses from the ECB’s policies, much of the problem stems from the country’s reluctance to ease its own fiscal policy.

While the Federal Reserve in the United States has made the first steps on the bumpy road towards policy normalisation following the financial crisis, in Europe the ECB continues to fire new shots from its monetary ‘bazooka’.

In doing so, however, it has faced growing resistance, above all in Germany. In mid-April, conservative politicians launched a coordinated attack on Mario Draghi and his Niedrigzinspolitik (low-interest-rate policy). Among other leading figures from the CDU and CSU, the Bavarian finance minister called on Berlin to “demand a change of direction in monetary policy”, which was “an attack on the wealth of millions of Germans”.

Wolfgang Schäuble said Draghi was responsible for half the votes that went to the right-wing AfD in recent regional elections. This unprecedented onslaught from the heart of the German political establishment marks a turning point in the political debate about the role and independence of the ECB. But it is important to understand why German indignation, although understandable, is ultimately unjustified.

The ECB and Germany

Quantitative easing (QE) began in the autumn of 2014, when the ECB began to purchase covered bonds and asset-backed securities. In March 2015, after the European Court of Justice had finally given the green light, the ECB fired its real ‘bazooka’, the Public Sector Purchase Programme. Under the terms of this Expanded Asset Purchase Programme (APP), the ECB conducted monthly purchases of public and private securities worth EUR 60 billion.

These purchases have re-inflated the balance sheet to EUR 3 trillion. In March 2016, the ECB further expanded the APP, adding corporate bonds as a fourth target asset class and raising the monthly target to EUR 80 billion. At the same meeting, the governing council also decided to reduce its main refinancing and deposit rates to 0 percent and -0.4 percent, respectively.

Within the governing council of the ECB, the main division continues to be between Germany (flanked by the Netherlands) and the southern European countries. As reported by the Financial Times, the four members of the governing council that opposed the latest easing package included the heads of the German and Dutch central banks, as well as German board member Sabine Lautenschlaeger.

Why these dissenting votes? With the inflation rate continuously undershooting the ECB’s target, the famous German Stabilitätskultur cannot provide a satisfying answer. Instead, the statements quoted above point toward hard-nosed economic interests, which Weidmann and Lautenschlaeger would have a hard time ignoring.

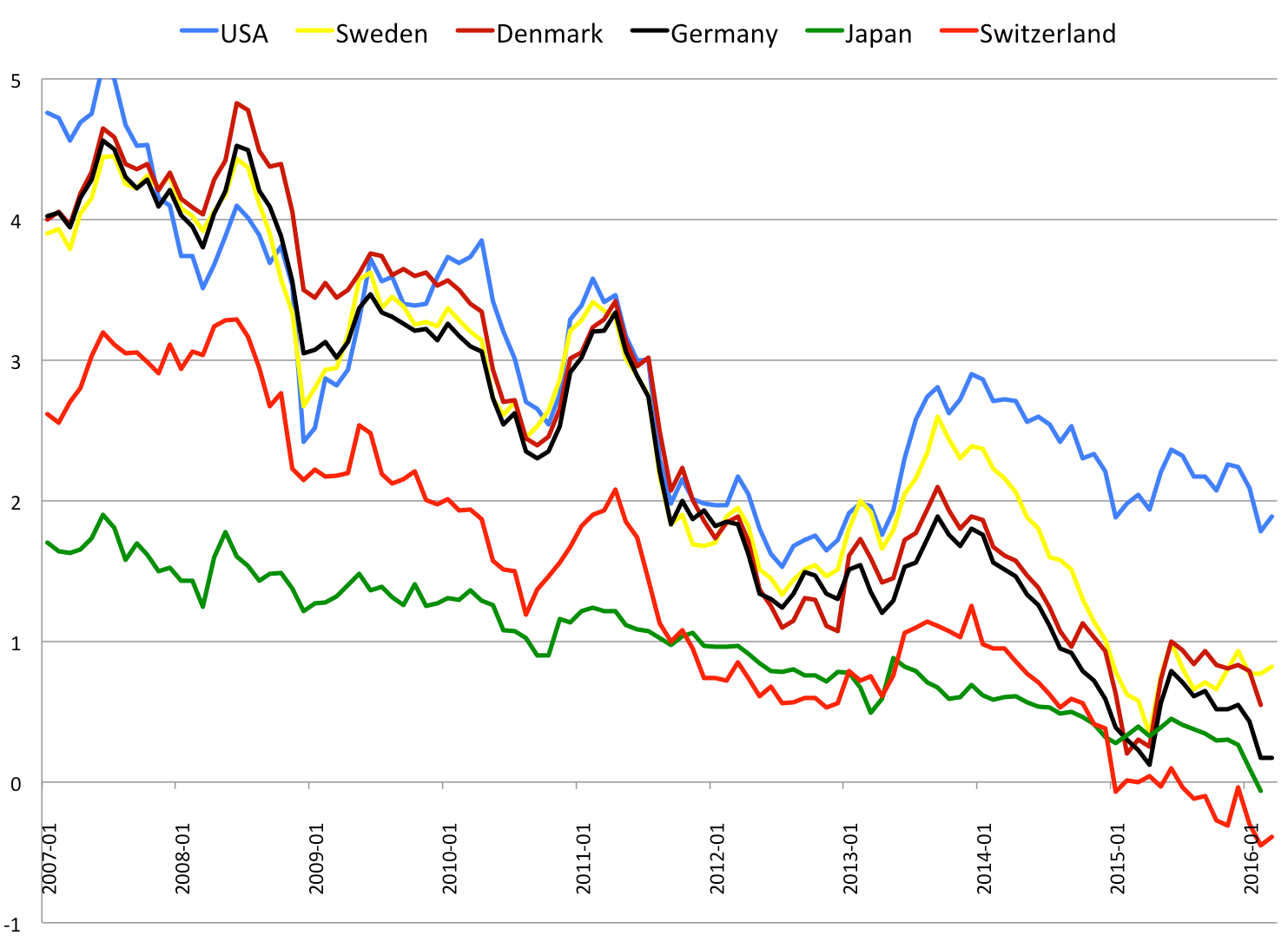

The two key interest groups are savers and bankers. Politicians in Germany claim that by keeping interest rates down, the ECB ‘expropriates’ the country’s savers. It is true that Germans do a lot of saving. It is also true that long-term interest rates have never been so low for so long. Figure 1 shows that 10-year government bond yields stand at or below zero for several countries. In April, the average yield across all outstanding German government bonds fell to zero for the first time in history.

Figure 1: Ten-year government bond yields, % per annum (Jan 2007- Mar 2016)

Source: OECD

According to numbers from DZ Bank, real interest rates below the average level of ‘normal’ times have imposed a net loss for German savers of 153 billion euros in the period from 2010 to 2015. While such estimates should be taken with a grain of salt, there are two substantial reasons why German savers are particularly affected.

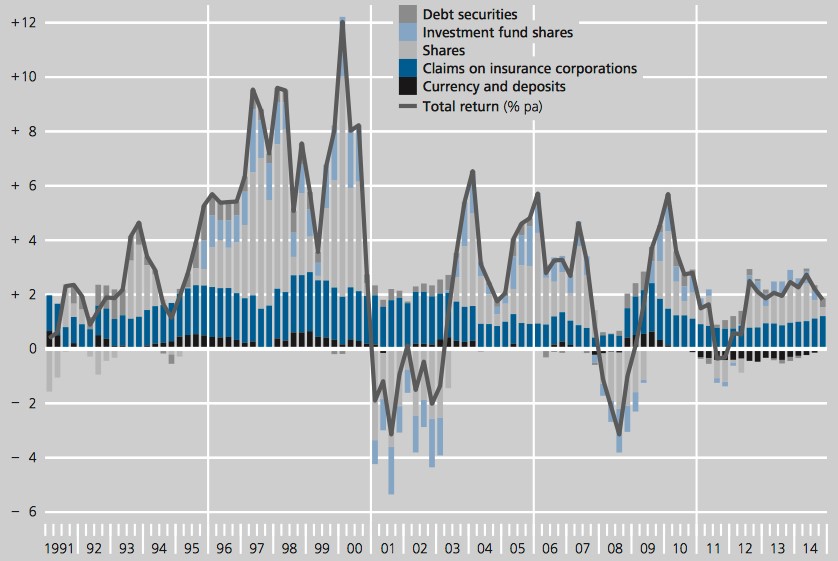

First, the large majority are under-invested in stocks and housing – two asset classes that have been boosted by QE. Second, German households are less indebted than their counterparts in high-homeownership countries such as Ireland or the Netherlands. Since mortgage holders benefit both from low interest rates and from rising house prices, this further reduces the gains German households reap from ultra-loose monetary policy. Still, talk of ‘expropriation’ is exaggerated. As shown in Figure 2 – provided by the Bundesbank – the real return German savers received on their financial assets since 2011 has remained safely in positive territory. At least as far as the Bundesbank is concerned, this points towards other interests as potentially more relevant.

Figure 2: Contribution of individual types of financial assets to the real total return of households in Germany, percentage points

Note: assets are weighted according to share of total financial assets. Source: Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report October 2015, p. 13.

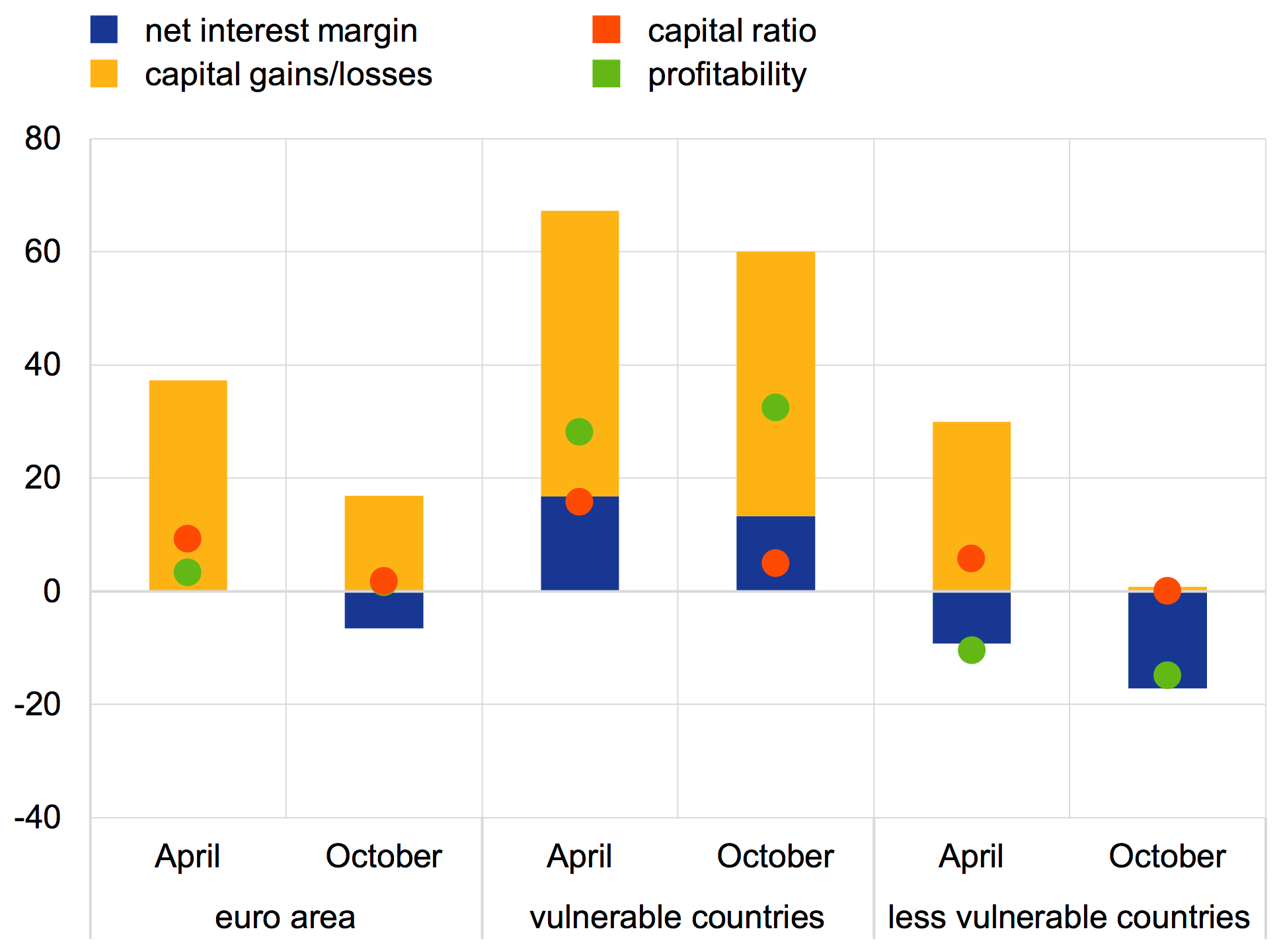

Indeed, the core constituency of central bankers are not the households, but bankers. According to the minutes of the March meeting, the decision of the governing council was based on the assessment that across the euro area, banks “benefit from the low interest rate environment, as a decline in interest revenues was more than compensated for by lower costs of funding and an expansion in credit volumes, together with possible holding gains on assets.”

However, as in the case of households, there is a geographical dimension. The ECB’s positive assessment is based on data from the ECB’s quarterly bank lending survey, illustrated in Figure 3. The green dots show that the impact of QE on bank profitability has been positive for the euro area as a whole. Crucially, however, that impact has been very positive for banks in ‘vulnerable’ countries, but negative for banks in the remaining countries, including Germany.

Figure 3: Impact of the APP on euro area banks’ profitability and capital position

Note: The figure shows the net percentage of respondents in the April and October 2015 bank lending surveys. Source: ECB Economic Bulletin, 1/2016, p. 35.

This is because weak banks that hold distressed bonds and non-performing loans on their balance sheets have experienced capital gains, benefitting from higher asset prices. Strong banks, on the other hand, have suffered from the QE-induced compression of their interest margin. Their business model depends on the spread between the short-term rate they pay on deposits and the long-term rates they charge their borrowers. With yields on ten-year government bonds hovering around zero, this spread has all but disappeared. The head of the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority recently spoke of low interest rates as “seeping poison” for Germany’s banks.

The costs of adjustment: Germany must lose some, too

We have seen that the gains and losses from QE and ultra-low interest rates are distributed unequally across the euro area. The number of net-losers is likely to be higher in Germany than elsewhere. Does this mean that Schäuble and his party are correct to concentrate their fire on the ECB?

The answer is clearly no. The immediate reason is that the contractionary stance of current fiscal policy effectively forced the ECB to escalate monetary easing. Hitting back at German accusations, Mario Draghi said as much at the ECB’s April press conference.

But there is also a second, deeper reason. As a result of previous divergence within the euro area, resolving the current crisis requires macroeconomic adjustment. In a world more economically reasonable than this one, higher wages and prices in Germany would have made a sizeable contribution toward that adjustment. The country’s exporters would have taken on their fair share of the losses now absorbed by German savers and bankers.

The one actor that could still do something about this is, of course, the German government. By increasing the country’s sovereign debt it could boost public investment, raise the demand for capital, put upward pressure on interest rates, and ease the adjustment pressure on more vulnerable countries. Instead, Wolfgang Schäuble, reluctant to abandon his “schwarze Null fetish”, keeps insisting on a balanced budget. This German obsession with a misguided notion of fiscal rectitude leaves Mario Draghi no choice but to continue to test the limits of monetary policy.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Wolfgang Schäuble; credits: Metropolitico.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1NrnD0u

_________________________________

Benjamin Braun – Max Planck Institute

Benjamin Braun is a political economist based at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies. He tweets at @BJMBraun.