Matteo Renzi has been Italian Prime Minister since 2014, but has faced a number of challenges in retaining his support ahead of the next general election. James L. Newell writes that much will be revealed by the results of local elections in June, where Renzi’s party faces significant challenges, and beyond that by the usual problems of managing the economy in a country where growth remains weak and unemployment stubbornly high.

Matteo Renzi has been Italian Prime Minister since 2014, but has faced a number of challenges in retaining his support ahead of the next general election. James L. Newell writes that much will be revealed by the results of local elections in June, where Renzi’s party faces significant challenges, and beyond that by the usual problems of managing the economy in a country where growth remains weak and unemployment stubbornly high.

Throughout the democratic West, politics is becoming increasingly personal, a phenomenon that political scientists have, from varying perspectives, described as the ‘personalisation’, the ‘mediatisation’ or the ‘presidentialisation’ of politics. Essentially, the argument is this: the growing importance, as campaigning tools, of the broadcast, and now the digital, media, have meant that parties have had to adapt to the demands of these media and the way they cover politics. In particular, television and the press, in the constant search for audiences, focus more on the personal qualities of candidates and leaders and less on what they stand for: they need to seek to entertain as much as to inform.

As a consequence, parties need leaders who can become celebrities, leaders who, in the brave new world of the neo-liberal consensus, can convince audiences less of the intellectual or moral superiority of their platforms, than that they are ‘fit to govern’. Consequently, vis-à-vis their parties, leaders become increasingly powerful, being able to use the competitive advantage they bring to their parties as a means to acquire autonomy and control over policy. In turn, bringing electoral success to their parties enables leaders more effectively to control their parliamentary followers, thus bringing more effective control of the legislature by the executive.

These changes began to unfold in Italy relatively late, having had essentially to wait upon the emergence of commercial broadcasting in the 1980s, the party-system transformation of the 1990s and the political debut of Silvio Berlusconi that was the consequence of these two developments. Since then – as if to confirm popular stereotypes concerning Italy’s attachment to ‘politics as spectacle’ – colourful leaders have abounded, though until recently, they were for the most part leaders of the right.

The main coalition of the centre left, in particular, was reluctant, thanks to its traditions, to embrace the new style of campaigning introduced by Berlusconi; and when it attempted to field leaders with a chance of standing toe to toe with the entrepreneur, the effect was paradoxical: negative comparisons would raise the latter’s media profile and thus the centre-right’s competitive advantage even more.

Now the tables appear to be turned: the aging Berlusconi’s star is continuing to fade; the centre right is in consequent disarray, and the centre left has for the past two years had the more charismatic, the more powerful leader: the 41-year old former mayor of Florence, Matteo Renzi. On 22 February 2014, Renzi became the youngest person ever to have assumed the office of Prime Minister of Italy – whose importance on the world stage has recently been enhanced by its large national debt and the significance of this for the Eurozone crisis, and more recently still by its role as a front-line state in attempts to deal with the international refugee crisis. But after two years in office and with a view to the next general election, how is Renzi placed?

Matteo Renzi and his election prospects

In personal terms, Renzi is a man who comes across as relaxed on television and among the public, a lover of the witty riposte, one who respects but is more or less indifferent to social conventions. He has sometimes been compared to Tony Blair, combining an attachment to liberalism in the economic sphere with a progressive approach to civil rights and a suspicion of vested interests of all kinds.

The latter feature in particular lends to his style of political communication a distinctly populist hue: in effect he offers a softer version of the cocktail of anti-political sentiments peddled by Beppe Grillo and the Five-star Movement (M5S). Such a style finds a ready echo among Italian public opinion and is therefore central to Renzi’s approach to the mobilisation of support in the permanent campaign – but not only that: it was also central to his rise to power.

At the general election of 2013, the centre left had, through a poorly-run campaign, managed to confound initial expectations and, as in 2006, snatch near-defeat from the jaws of victory. Resignation of Pierluigi Bersani as secretary of the Democratic Party (PD) paved the way for the ascent of Renzi who had already staked his claim to the succession through an (unsuccessful) challenge to Bersani in a primary election to choose the centre left’s candidate premier, held at the end of 2012.

Crucial to Renzi’s victory at the end of 2013 were the PD’s attempts to meet the crisis of political engagement by opening elections for the party leader to supporters and sympathisers as well as members, and Renzi’s calls for rottamazione – demolition of the party’s traditional oligarchies through the resignation of old established leaders and their replacement by younger, fresher faces. Renzi was viewed with some suspicion by party activists, but was much more popular among party sympathisers who saw in the Florentine a politician capable of breathing life into a tired organisation and offering a policy revolution that would enable the PD to appeal to voters beyond its usual constituency.

The first solid evidence of this capacity came in the European elections of May 2014 when Renzi – having by then gone on to oust the incumbent Prime Minister in a ‘palace coup’ I’ve described, with Arianna Giovannini, elsewhere on this site – led his party to an historic victory with almost 41% of the vote. Since then, his premiership has gone on to become one of the half-dozen longest lasting since 1946 and he claims to have a number of legislative achievements to his credit.

These include the so-called Jobs Act, which has been welcomed by business and which Renzi claims (with whatever justification) has been responsible for recent encouraging increases in the rate of employment. They also include a major education reform; civil partnerships for same-sex couples, and, most significantly, seemingly incisive institutional reforms, including a new electoral law and an overhaul of Parliament’s second chamber, the Senate.

The latter will only come into force if confirmed by a popular referendum to be held in the autumn, on whose outcome Renzi has staked his entire political future, saying that he will ‘return home’ if the reforms are rejected. He has correctly perceived that a referendum victory will enable him to continue to dominate the stage of Italian politics. As he has framed the contest as a battle between the ‘new’ Italy and the ‘old’, it will enable him to dish the M5S, which has thrown its lot in with the ‘No’ campaigners, and the ever troublesome dissidents in his own party. It will enable him to pose as the architect of reforms that respond to long-standing and deep-seated demands for more efficient and effective government.

So what are Renzi’s prospects? On the one hand, opinion polls over the past couple of years have tended to suggest a clear referendum victory for the Prime Minister – though with much less certainty since Parliament gave its final approval to the reform in April and since, therefore, the issue has risen up the agenda and the two sides in the campaign have begun to square up to each other. Renzi may, therefore, still be Prime Minister at the end of 2016.

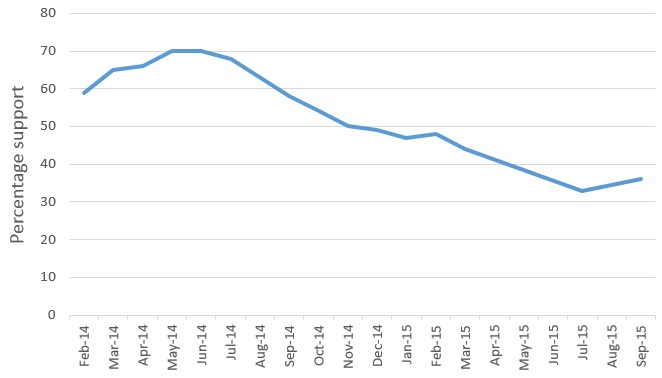

On the other hand, even if he is, the solidity of his position may not be as great as a referendum victory would, on its own suggest. For one thing, powerful as Renzi has been relative to other Italian prime ministers, compared to prime ministers elsewhere, he has still been relatively restricted by the vetoes of the party actors making up his majority. Consequently, he has been every bit as subject to that well-known curve of decreasing popularity whereby, following an initial ‘honeymoon’ period, the popularity of the head of the Government tends to follow a downward trend, as shown in the figure below.

Figure: Italian Prime Minister’s popularity ratings (Feb 2014 – Sep 2015)

Source: IPSOS polls

And in early 2016, polls were continuing to place confidence in him as Prime Minister in the early thirties. The problem is that Renzi, like all Prime Ministers, is caught up in a dilemma: in order to retain and increase his level of popularity, he needs to keep his majority united and so take decisive action – but in order to be successful in doing that he has to enjoy a high level of popularity. Much about Renzi’s capacity to manage this dilemma will be revealed by the results of the local elections next month, where his party faces significant challenges, and beyond that by the usual problems of managing the economy in a country where growth remains weak and unemployment stubbornly high. Watch this space!

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1NJ7ljF

_________________________________

James L. Newell – University of Salford

James L. Newell – University of Salford

James L. Newell is Professor of Politics in the School of Arts and Media at the University of Salford. He recently edited a special issue of the Italian journal Polis on Politics, citizens’ engagement and the state of democracy in Italy and UK with Arianna Giovannini. He is Treasurer of the PSA’s Italian Politics Specialist Group.